Sometime about the year AD 117, the Ninth Legion, which was stationed at Eburacum where York now stands, marched north to deal with a rising among the Caledonian tribes, and was never heard of again.

During the excavations at Silchester nearly eighteen hundred years later, there was dug up under the green fields which now cover the pavements of Calleva Atrebatum, a wingless Roman Eagle, a cast of which can be seen to this day in Reading Museum. Different people have had different ideas as to how it came to be there, but no one knows, just as no one knows what happened to the Ninth Legion after it marched into the northern mists.

It is from these two mysteries, brought together, that I have made the story of The Eagle of the Ninth.

III

Attack!

In the dark hour before the dawn . . . Marcus was roused out of his sleep by the Duty Centurion. A pilot lamp always burned in his sleeping-cell against just such an emergency, and he was fully awake on the instant.

‘What is it, Centurion?’

‘The sentries on the south rampart report sounds of movement between us and the town, sir.’

Marcus was out of bed and had swung his heavy military cloak over his sleeping-tunic. ‘You have been up yourself?’

The centurion stood aside for him to pass out into the darkness. ‘I have, sir,’ he said with grim patience. ‘Anything to be seen?’

‘No, sir, but there is something stirring down there, for all that.’ Quickly they crossed the main street of the fort, and turned down beside a row of silent workshops. Then they were mounting the steps to the rampart walk. The shape of a sentry’s helmet rose dark against the lesser darkness above the breastwork, and there was a rustle and thud as he grounded his pilum in salute.

Marcus went to the breast-high parapet. The sky had clouded over so that not a star was to be seen, and all below was a formless blackness with nothing visible save the faint pallor of the river looping through it. Not a breath of air stirred in the stillness, and Marcus, listening, heard no sound in all the world save the whisper of the blood in his own ears, far fainter than the sea in a conch-shell.

He waited, breath in check; then from somewhere below came the kee-wick, kee-wick, wick-wick, of a hunting owl, and a moment later a faint and formless sound of movement that was gone almost before he could be sure that he had not imagined it. He felt the Duty Centurion grow tense as a strung bow beside him. The moments crawled by, the silence became a physical pressure on his eardrums. Then the sounds came again, and with the sounds, blurred forms moved suddenly on the darkness of the open turf below the ramparts.

Marcus could almost hear the twang of breaking tension. The sentry swore softly under his breath, and the centurion laughed.

‘Somebody will be spending a busy day looking for his strayed cattle!’

Strayed cattle; that was all. And yet for Marcus the tension had not snapped into relief. Perhaps if he had never seen the new heron’s feathers on an old war spear it might have done, but he had seen them, and somewhere deep beneath his thinking mind the instinct for danger had remained with him ever since. Abruptly he drew back from the breast-work, speaking quickly to his officer. ‘All the same, a break-out of cattle might make good cover for something else. Centurion, this is my first command: if I am being a fool, that must excuse me. I am going back to get some more clothes on. Turn out the cohort to action stations as quietly as may be.’

And not waiting for a reply, he turned, and dropping from the rampart walk, strode off towards his own quarters.

In a short while he was back, complete from studded sandals to crested helmet, and knotting the crimson scarf about the waist of his breast-plate as he came. From the faintly lit doorways of the barrack rows, men were tumbling out, buckling sword-belts or helmet-straps as they ran, and heading away into the darkness. ‘Am I being every kind of fool?’ Marcus wondered. ‘Am I going to be laughed at so long as my name is remembered in the Legion, as the man who doubled the guard for two days because of a bunch of feathers, and then turned out his cohort to repel a herd of milch-cows?’ But it was too late to worry about that now. He went back to the ramparts, finding them already lined with men, the reserves massing below. Centurion Drusillus was waiting for him, and he spoke to the older man in a quick, miserable undertone. ‘I think I must have gone mad, Centurion; I shall never live this down.’

‘Better to be a laughing-stock than lose the fort for fear of being one,’ returned the centurion. ‘It does not pay to take chances on the frontier – and there was a new moon last night.’

Marcus had no need to ask his meaning. In his world the gods showed themselves in new moons, in seed-time and harvest, summer and winter solstice; and if an attack were to come, the new moon would be the time for it. Holy War. Hilarion had understood all about that. He turned aside to give an order. The waiting moments lengthened; the palms of his hands were sticky, and his mouth uncomfortably dry.

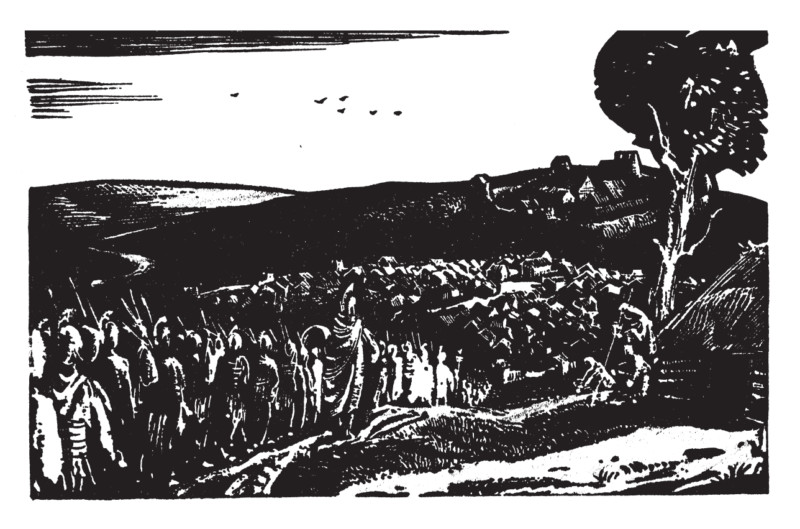

The attack came with a silent uprush of shadows that swarmed in from every side, flowing up to the turf ramparts with a speed, an impetus that, ditch or no ditch, must have carried them over into the camp if there had been only the sentries to bar the way. They were flinging brushwood bundles into the ditch to form causeways; swarming over, they had poles to scale the ramparts, but in the dark nothing of that could be seen, only a flowing up and over, like a wave of ghosts. For a few moments the utter silence gave sheer goose-flesh horror to the attack; then the auxiliaries rose as one man to meet the attackers, and the silence splintered, not into uproar, but into a light smother of sound that rippled along the ramparts: the sound of men fiercely engaged, but without giving tongue. For a moment it endured; and then from the darkness came the strident braying of a British war-horn. From the ramparts a Roman trumpet answered the challenge, as fresh waves of shadows came pouring in to the attack; and then it seemed as if all Tartarus had broken loose. The time for silence was past, and men fought yelling now; red flame sprang up into the night above the Praetorian gate, and was instantly quenched. Every yard of the ramparts was a reeling, roaring battle-line as the tribesmen swarmed across the breastwork to be met by the grim defenders within.

How long it lasted Marcus never knew, but when the attack drew off, the first cobweb light of a grey and drizzling dawn was creeping over the fort. Marcus and his second-in-command looked at each other, and Marcus asked very softly, ‘How long can we hold out?’

‘For several days, with luck,’ muttered Drusillus, pretending to adjust the strap of his shield.

‘Reinforcements could get to us in three – maybe two – from Durinum,’ Marcus said. ‘But there was no reply to our signal.’

‘Little to wonder in that, sir. To destroy the nearest signal station is an obvious precaution; and no cresset could carry the double distance in this murk.’

‘Mithras grant it clears enough to give the smoke column a chance to rise.’

But there was no sign of anxiety in the face of either of them when they turned from each other an instant later, the older man to go clanging off along the stained and littered rampart walk, Marcus to spring down the steps into the crowded space below. He was a gay figure, his scarlet cloak swirling behind him; he laughed, and made the ‘thumbs up’ to his troops, calling ‘Well done, lads! We will have breakfast before they come on again!’

The ‘thumbs up’ was returned to him. Men grinned, and here and there a voice called cheerfully in reply, as he disappeared with Centurion Paulus in the direction of the Praetorium.

No one knew how long the breathing space might last; but at the least it meant time to get the wounded under cover, and an issue of raisins and hard bread to the troops. Marcus himself had no breakfast, he had too many other things to do, too many to think about; amongst them the fate of a half Century under Centurion Galba, now out on patrol, and due back before noon. Of course the tribesmen might have dealt with them already, in which case they were beyond help or the need of it, but it was quite as likely that they would merely be left to walk into the trap on their return, and cut to pieces under the very walls of the fort.

Marcus gave orders that the cresset was to be kept alight on the signal roof; that at least would warn them that something was wrong as soon as they sighted it. He ordered a watch to be kept for them, and sent for Lutorius of the Cavalry and put the situation to him. ‘If they win back here, we shall of course make a sortie and bring them in. Muster the squadron and hold them in readiness from now on. That is all.’

‘Sir,’ said Lutorius. His sulks were forgotten, and he looked almost gay as he went off to carry out the order.

There was nothing more that Marcus could do about his threatened patrol, and he turned to the score of other things that must be seen to.

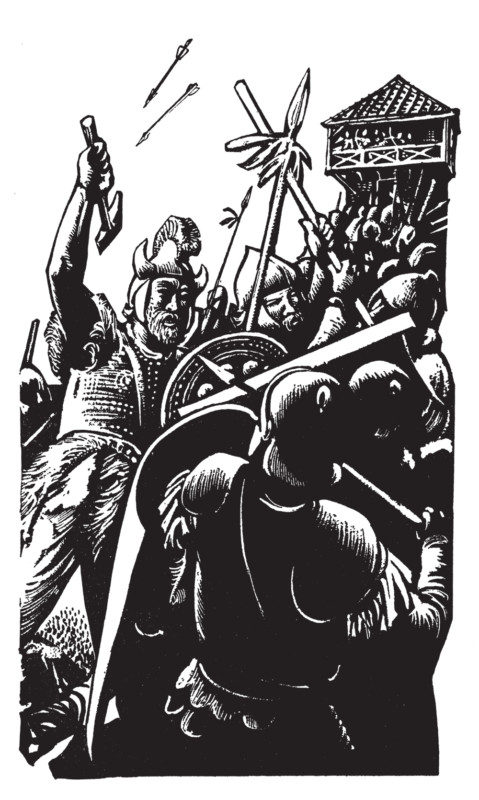

It was full daylight before the next attack came. Somewhere, a war-horn brayed, and before the wild note died, the tribesmen broke from cover, yelling like fiends out of Tartarus as they swarmed up through the bracken; heading for the gates this time, with tree-trunks to serve as rams, with firebrands that gilded the falling mizzle and flashed on the blade of sword and heron-tufted war spear. On they stormed, heedless of the Roman arrows that thinned their ranks as they came. Marcus, standing in the shooting turret beside the Praetorian gate, saw a figure in their van, a wild figure in streaming robes that marked him out from the half-naked warriors who charged behind him. Sparks flew from the firebrand that he whirled aloft, and in its light the horns of the young moon, rising from his forehead, seemed to shine with a fitful radiance of their own. Marcus said quietly to the archer beside him, ‘Shoot me that maniac.’

The man nocked another arrow to his bow, bent and loosed it in one swift movement. The Gaulish Auxiliaries were fine bowmen, as fine as the British; but the arrow sped out only to pass through the wild hair of the leaping fanatic. There was no time to loose again. The attack was thundering on the gates, pouring in over the dead in the ditch with a mad courage that took no heed of losses. In the gate towers the archers stood loosing steadily into the heart of the press below them. The acrid reek of smoke and smitch drifted across the fort from the Dexter Gate, which the tribesmen had attempted to fire. There was a constant two-way traffic of reserves and armament going up to the ramparts and wounded coming back from them. No time to carry away the dead; one toppled them from the rampart walk that they might not hamper the feet of the living, and left them, though they had been one’s best friend, to be dealt with at a fitter season.

The second attack drew off at last, leaving their dead lying twisted among the trampled fern. Once more there was breathing space for the desperate garrison. The morning dragged on; the British archers crouched behind the dark masses of uprooted blackthorn that they had set up under cover of the first assault, and loosed an arrow at any movement on the ramparts; the next rush might come at any moment. The garrison had lost upward of fourscore men, killed or wounded: two days would bring them reinforcements from Durinum, if only the mizzle which obscured the visibility would clear, just for a little while, long enough for them to send up the smoke signal, and for it to be received.

But the mizzle showed no signs of lifting, when Marcus went up to the flat signal-roof of the Praetorium. It blew in his face, soft and chill-smell-ing, and faintly salt on his lips. Faint grey swathes of it drifted across the nearer hills, and those beyond were no more than a spreading stain that blurred into nothingness.

‘It is no use, sir,’ said the auxiliary who squatted against the parapet, keeping the great charcoal brazier glowing.

Marcus shook his head. Had it been like this when the Ninth Legion ceased to be? he wondered. Had his father and all those others watched, as he was watching now, for the far hills to clear so that a signal might go through? Suddenly he found that he was praying, praying as he had never prayed before, flinging his appeal for help up through the grey to the clear skies that were beyond. ‘Great God Mithras, Slayer of the Bull, Lord of the Ages, let the mists part and thy glory shine through! Draw back the mists and grant us clear air for a space, that we go not down into the darkness. O God of the Legions, hear the cry of thy sons. Send down thy light upon us, even upon us, thy sons of the Fourth Gaulish Cohort of the Second Legion.’

He turned to the auxiliary, who knew only that the Commander had stood beside him in silence for a few moments, with his head tipped back as though he was looking for something in the soft and weeping sky. ‘All we can do is wait,’ he said. ‘Be ready to start your smother at any moment.’ And swinging on his heel, he rounded the great pile of fresh grass and fern that lay ready near the brazier, and went clattering down the narrow stairway.

Centurion Fulvius was waiting for him at the foot with some urgent question that must be settled, and it was some while before he snatched another glance over the ramparts; but when he did, it seemed to him that he could see a little farther than before. He touched Drusillus, who was beside him, on the shoulder. ‘Is it my imagining, or are the hills growing clearer?’

Drusillus was silent a moment, his grim face turned towards the east. Then he nodded. ‘If it is your imagining, it is also mine.’ Their eyes met quickly, with hope that they dared not put into any more words; then they went each about their separate affairs.

But soon others of the garrison were pointing, straining their eyes east-ward in painful hope. Little by little the light grew: the mizzle was lifting, lifting . . . and ridge behind wild ridge of hills coming into sight.

High on the Praetorium roof a column of black smoke sprang upward, billowed sideways and spread into a drooping veil that trailed across the northern rampart, making the men there cough and splutter; then rose again, straight and dark and urgent, into the upper air.

In the pause that followed, eyes and hearts were strained with a sickening intensity toward those distant hills. A long, long pause it seemed; and then a shout went up from the watchers, as, a day’s march to the east, a faint dark thread of smoke rose into the air.

The call for help had gone through. In two days, three at the most, relief would be here; and the uprush of confidence touched every man of the garrison.

Barely an hour later, word came back to Marcus from the northern rampart that the missing patrol had been sighted on the track that led to the Sinister Gate. He was in the Praetorium when the word reached him, and he covered the distance to the gate as if his heels were winged; he waved up the Cavalry waiting beside their saddled horses, and found Centurion Drusillus once again by his side.

‘The tribesmen have broken cover, sir,’ said the centurion.

Marcus nodded. ‘I must have half a Century of the reserves. We can spare no more. A trumpeter with them and every available man on the gate, in case they try a rush when it opens.’

The centurion gave the order, and turned back to him. ‘Better let me take them, sir.’

Marcus had already unclasped the fibula at the shoulder of his cloak, and flung off the heavy folds that might hamper him.

‘We went into that before. You can lend me your shield, though.’

The other slipped it from his shoulder without a word, and Marcus took it and swung round on the half Century who were already falling in abreast of the gate. ‘Get ready to form testudo,’ he ordered. ‘And you can leave room for me. This tortoise is not going into action with its head stuck out!’

It was a poor joke, but a laugh ran through the desperate little band, and as he stepped into his place in the column head, Marcus knew that they were with him in every sense of the word; he could take those lads through the fires of Tophet if need be.

The great bars were drawn, and men stood ready to swing wide the heavy valves; and behind and on every side he had a confused impression of grim ranks massed to hold the gate, and draw them in again if ever they won back to it.

‘Open up!’ he ordered; and as the valves began to swing outward on their iron-shod posts, ‘Form testudo.’ His arm went up as he spoke, and through the whole column behind him he felt the movement echoed, heard the light kiss and click of metal on metal, as every man linked shield with his neighbour, to form the shield-roof which gave the formation its name. ‘Now!’

The gates were wide; and like a strange many-legged beast, a gigantic woodlouse rather than a tortoise, the testudo was out across the causeway and heading straight downhill, its small, valiant cavalry wings spread on either side. The gates closed behind it, and from rampart and gate-tower anxious eyes watched it go. It had all been done so quickly that at the foot of the slope battle had only just joined, as the tribesmen hurled themselves yelling on the swiftly formed Roman square.

The testudo was not a fighting formation; but for rushing a position, for a break through, it had no equal. Also it had a strange and terrifying aspect that could be very useful. Its sudden appearance now, swinging down upon them with the whole weight of the hill behind it, struck a brief confusion into the swarming tribesmen. Only for a moment their wild ranks wavered and lost purpose; but in that moment the hard-pressed patrol saw it too, and with a hoarse shout came charging to join their comrades.

Down swept Marcus and his half Century, down and forward into the raging battle-mass of the enemy. They were slowed almost to a standstill, but never quite halted; once they were broken, but reformed. A mailed wedge cleaving into the wild ranks of the tribesmen, until the moment came when the tortoise could serve them no longer; and above the turmoil Marcus shouted to the trumpeter beside him: ‘Sound me “Break testudo”.’

The clear notes of the trumpet rang through the uproar. The men lowered their shields, springing sideways to gain fighting space; and a flight of pilums hurtled into the swaying horde of tribesmen, spreading death and confusion wherever the iron heads struck. Then it was ‘Out swords’, and the charge driven home with a shout of ‘Caesar! Caesar!’ Behind them the valiant handful of cavalry were struggling to keep clear the line of retreat; in front, the patrol came grimly battling up to join them. But between them was still a living rampart of yelling, battle-frenzied warriors, amongst whom Marcus glimpsed again that figure with the horned moon on its forehead. He laughed, and sprang against them, his men storming behind him.

Patrol and relief force joined, and became one.

Instantly they began to fall back, forming as they did so a roughly diamond formation that faced outward on all sides and was as difficult to hold as a wet pebble pressed between the fingers. The tribesmen thrust in on them from every side, but slowly, steadily, their short blades like a hedge of living, leaping steel, the cavalry breaking the way for them in wild rushes, they were drawing back towards the fortress gate – those that were left of them.

Back, and back. And suddenly the press was thinning, and Marcus, on the flank, snatched one glance over his shoulder, and saw the gate-towers very near, the swarming ranks of the defenders ready to draw them in. And in that instant there came a warning yelp of trumpets and a swelling thunder of hooves and wheels, as round the curve of the hill towards them, out of cover of the woodshore, swept a curved column of chariots.

Small wonder that the press had thinned.

The great battle-wains had long been forbidden to the tribes, and these were light chariots such as the one Marcus had driven two days ago, each carrying only a spearman beside the driver; but one horrified glance, as they hurtled nearer behind their thundering teams, was enough to show the wicked, whirling scythe-blades on the war-hubs of the wheels.

Close formation – now that their pilums were spent – was useless in the face of such a charge; again the trumpets yelped an order, and the ranks broke and scattered, running for the gateway, not in any hope of reaching it before the chariots were upon them, but straining heart and soul to gain the advantage of the high ground.

To Marcus, running with the rest, it seemed suddenly that there was no weight in his body, none at all. He was filled through and through with a piercing awareness of life and the sweetness of life held in his hollowed hand, to be tossed away like the shining balls that the children played with in the gardens of Rome. At the last instant, when the charge was almost upon them, he swerved aside from his men, out and back on his tracks, and flinging aside his sword, stood tensed to spring, full in the path of the oncoming chariots. In the breath of time that remained, his brain felt very cold and clear, and he seemed to have space to do quite a lot of thinking. If he sprang for the heads of the leading team, the odds were that he would merely be flung down and driven over without any check to the wild gallop. His best chance was to go for the charioteer. If he could bring him down, the whole team would be flung into confusion, and on that steep scarp the chariots coming behind would have difficulty in clearing the wreck. It was a slim chance, but if it came off it would gain for his men those few extra moments that might mean life or death. For himself, it was death. He was quite clear about that.

They were right upon him, a thunder of hooves that seemed to fill the universe; black manes streaming against the sky; the team that he had called his brothers, only two days ago. He hurled his shield clanging among them, and side-stepped, looking up into the grey face of Cradoc, the charioteer. For one splinter of time their eyes met in something that was almost a salute, a parting salute between two who might have been friends; then Marcus leapt in under the spearman’s descending thrust, upward and sideways across the chariot bow. His weight crashed on to the reins, whose ends, after the British fashion, were wrapped about the charioteer’s waist, throwing the team into instant chaos; his arms were round Cradoc, and they went half down together. His ears were full of the sound of rending timber and the hideous scream of a horse. Then sky and earth changed places, and with his hold still unbroken, he was flung down under the trampling hooves, under the scythe-bladed wheels and the collapsing welter of the overset chariot; and the jagged darkness closed over him.