I live in east London in a second-floor flat with no garden. My groceries come from the local corner shop and, when I feel strong enough to face it, from the hellhole of a supermarket in Whitechapel. I grow some herbs in pots on my windowsill. The sage and rosemary do quite well but the coriander, tarragon, mint and parsley remain spindly however much I coax them. I have been known to forage for elderflowers, nettles and blackberries in Victoria Park and once, while visiting Dungeness, I broke off some sea kale from the shingle to eat with the kippers I had bought from a smokery there, then quickly had to hide it on realizing from a sign that it was a plant from an area of special scientific interest and I was liable for a £3,000 fine. I ate it anyway. It was . . . interesting.

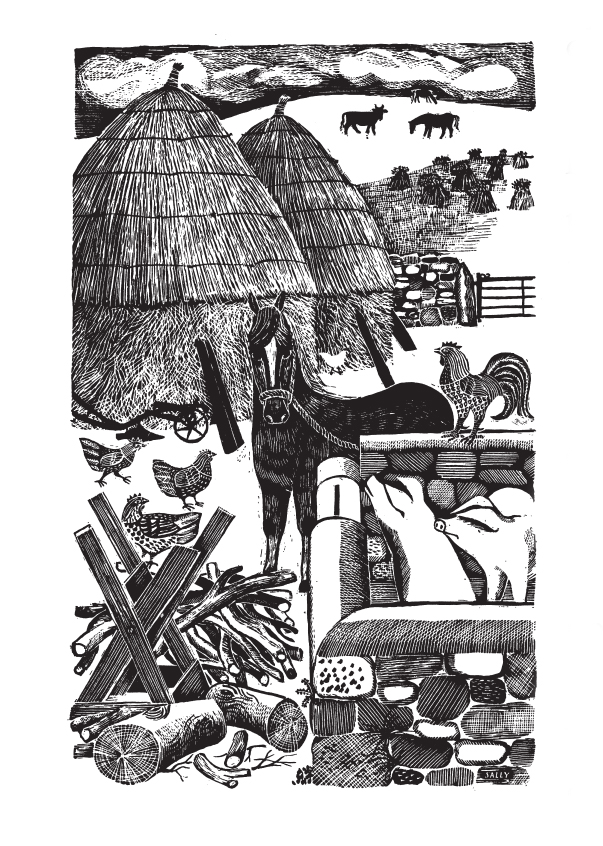

In short, I am not in the least self-sufficient. And yet two books that have always had a strong influence on my imagination are the ‘back-to-the-land’ classics by John Seymour – The Fat of the Land (1961) and Self-Sufficiency (1973). My copies are the original editions, published by Faber, with beautiful woodcut illustrations by the author’s wife, Sally Seymour, depicting their self-sufficient rustic life in Suffolk and Wales, and diagrams of things that I will probably never need to know if I carry on living as I do, such as how to prune a fruit tree, how to dig a drainage trench in a field, the different parts of pig and beef carcasses (incorporating the visceral mysteries of the cod fat, the goose skirt, the kidney knob and the sticking), and ‘the “monk” device for controlling water level in fishponds’. Seymour never explains what this device has to do with monks and admits ‘I have never done fish farming, but simply write so much about it in the possibility that it will arouse interest in someone with more energy than I have.’

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI live in east London in a second-floor flat with no garden. My groceries come from the local corner shop and, when I feel strong enough to face it, from the hellhole of a supermarket in Whitechapel. I grow some herbs in pots on my windowsill. The sage and rosemary do quite well but the coriander, tarragon, mint and parsley remain spindly however much I coax them. I have been known to forage for elderflowers, nettles and blackberries in Victoria Park and once, while visiting Dungeness, I broke off some sea kale from the shingle to eat with the kippers I had bought from a smokery there, then quickly had to hide it on realizing from a sign that it was a plant from an area of special scientific interest and I was liable for a £3,000 fine. I ate it anyway. It was . . . interesting.

In short, I am not in the least self-sufficient. And yet two books that have always had a strong influence on my imagination are the ‘back-to-the-land’ classics by John Seymour – The Fat of the Land (1961) and Self-Sufficiency (1973). My copies are the original editions, published by Faber, with beautiful woodcut illustrations by the author’s wife, Sally Seymour, depicting their self-sufficient rustic life in Suffolk and Wales, and diagrams of things that I will probably never need to know if I carry on living as I do, such as how to prune a fruit tree, how to dig a drainage trench in a field, the different parts of pig and beef carcasses (incorporating the visceral mysteries of the cod fat, the goose skirt, the kidney knob and the sticking), and ‘the “monk” device for controlling water level in fishponds’. Seymour never explains what this device has to do with monks and admits ‘I have never done fish farming, but simply write so much about it in the possibility that it will arouse interest in someone with more energy than I have.’ However, Seymour did do practically everything else that he wrote about in these two books, and in doing so he aroused the interest of a swathe of people in the late Sixties and early Seventies who wanted to turn their backs on the soulless commercialism of the modernworld and seek out ‘the good life’. Two of those people were my parents, to whom my copies of these books originally belonged. They married in 1973 and I was born in 1974. For the first few years of my life we lived in a small cottage on the Isle of Wight. My parents kept goats, two of them named Bella and Katy, and also bees, and a vegetable patch. By the time I was 6 we had left the Isle of Wight and moved to Stourbridge in the West Midlands. There, my dad built me a tree house, and for years I kept the two John Seymour books in it and pondered over them. In retrospect, it seems an odd thing for a child to do. I didn’t really read them, just looked at their pictures and imbibed their vibe; I liked the idea that if I wasn’t living in the midst of the West Midlands conurbation, if I wasn’t just a kid and had access to fields of cows and barley, I could follow John Seymour’s instructions and make myself some cheese and beer. I was also obsessed with Huckleberry Finn. Somehow Huck’s vagabond lifestyle on the Mississippi and John Seymour’s didactic manuals on how to live off the land conflated in my mind into a prelapsarian ideal that I still dream about now. John Seymour was an extraordinarily energetic and, reading between the lines of his obituaries, exhausting character. But he was clearly charismatic and inspired devotion in those who knew him. His daughter Ann said of him at his funeral, ‘He roared through life with the heart of an elephant, and the courage of a lion.’ He was born in 1914 and died in 2004, crammed several careers, three wives and six children into his ninety years, and wrote forty-one books on rural crafts, travel, gardening and self-sufficiency. Of upper middle-class stock, he declined to go into his millionaire stepfather’s chewing-gum business and, instead, studied agriculture at Wye College in Kent. Thereafter, he worked in South Africa on a sheep farm, in a copper mine and for the government veterinary service, while also spending much time with Bushmen, gaining an insight into hunter-gathering. During the war he fought with a Kenyan regiment of the British Army and afterwards moved back to England where he worked on a Thames sailing barge, and then as a civil servant for the Ministry of Agriculture, finding farm work for former German prisoners-of-war who had stayed on in Britain. He then moved into journalism and broadcasting for the BBC. In 1954 he married his first wife, Sally Medworth, an Australian potter. For a while they lived on a Dutch sailing smack but eventually, finding this impractical for family life, they rented two small adjoining cottages on five acres of land near Orford in Suffolk, and fell into self-sufficiency as they brought up their three daughters. The Fat of the Land describes the process of how they built up their cottage economy, starting with a cow, then pigs, then a horse to plough their land and pull them in a cart around the countryside (Seymour disdained cars and tractors), until they produced everything they needed to live except salt, sugar, flour, tea and coffee. And, as Seymour writes on the first page, ‘We could (and probably soon will anyway) produce our own flour, honey could (and if I can overcome my natural repugnance to the inhabitants of the two bee hives that we have soon will) take the place of sugar. Salt we could get by evaporating sea water on a nearby beach over a drift-wood fire. Tea and coffee we could no doubt learn to do without.’ Self-Sufficiency, subtitled The Science & Art of Producing & Preserving Your Own Food, is more of a manual and less of a narrative than The Fat of the Land and was written twelve years later, by which time Seymour and his wife had moved to a farm in Pembrokeshire. It is, however, no less absorbing. Seymour tells you in a straightforward, casual way exactly how and when to breed cows – ‘a cow shows that she is bulling by mounting other cows in a lesbian fashion’; how to slaughter said cow (or pig or chicken); how to cure bacon; how to malt barley and brew it into beer; how to make different kinds of cheese; what kind of wood is best for smoking fish; where to find cockles and clams on a beach; and a hundred other fascinating things besides. Along the way you learn the meaning of all sorts of obscure words, such as ‘cheddaring’, ‘sparging’ and ‘gaffing’, and even if you know you will never have the time, the opportunity or even the inclination to do any of these things, it is wonderfully reviving to be plunged into this wholesome world. It has to be admitted, though, that Seymour’s prose can seem irritatingly de haut en bas and that a whiff of smug self-righteousness hangs over both books. In the chapter devoted to fish in Self- Sufficiency he writes, ‘The industrial working man’s sport of catching fish out of fresh water canals, lakes and streams, weighing them, and throwing them back again, is as puerile as pulling wings off flies, but I suppose it is better than watching hired men playing football, for at least it gets its devotees away from a crowd.’ In the Garden Crops chapter he opines, ‘if the “average housewife” spent half the time that she spends in that silly occupation shopping cultivating a small garden at least she would never have to spend any of her housekeeping money on vegetables’. I would be fascinated to read an honest account by Sally Seymour or his children of what ‘the good life’ was like for them, for it is hard to believe that living off the land is as easy to learn as Seymour claims from what he calls ‘Old Mother Common Sense’. His vehemence against the modern world can also become wearying and at times makes me want to rush to Oxford Street, with my ears plugged into hip hop on my iPod, and drop a load of my indisposable income on impractical shoes. But, despite these caveats, Seymour is an inspiring writer. He captures the happy, industrious flavour of his family’s life on their Suffolk and Pembrokeshire smallholdings beautifully, and his enthusiasm is such that you immediately want to try what he did for yourself. Although he was harking back to earlier advocates of the simple life, such as William Cobbett and Thoreau, these two books, which came out at a time when the first serious doubts were being expressed about our dependence on fossil fuels and the ecological sustainability of a global economy, were utterly in tune with their era. He is the forerunner of people such as Jamie Oliver and Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, who continue to inspire people to grow and make their own food, and his ideas on small-scale, organic farming, reviving traditional husbandry and craft skills and local bartering economies are practised by the burgeoning ‘transition towns’ movement and by ecological protests such as the Climate Camps. His philosophy during a time in which we are, as we keep being told, on the eve of an environmental apocalypse is as relevant as ever. And, for me personally, it redresses the balance in a world where I am bombarded by news of talentless celebrities’ doings, emails exhorting me to buy unnecessary things at knock-down prices and other people’s bellowing mobile phone conversations. John Seymour’s books have an important place in the tree house of my mind.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 26 © Rowena Macdonald 2010

About the contributor

Rowena Macdonald’s fiction has been published in a number of anthologies. She teaches creative writing at Westminster University and also works at the House of Commons, the setting for a novel she is currently writing.