When I was but a boy and a bit in the last World War, I had a dream. I walked down Polstead Road in Oxford to Aristotle Lane. And I stopped off by the canal with my fishing-rod before going over the shuddering railway bridge on to the vast expanse of Port Meadow with its snapping swans. ‘Break your leg, they can,’ I was told. ‘With one chop of their beak.’

I tried to catch tiddlers, the dace and the roach, and put them in a jam-jar, though they were too muddy to eat. Sometimes a shire horse would plod up the canal path. It towed on a rope a dark barge, yet bright with painted colours, on its way to Tartary or beyond. Or so I supposed. Steering the craft, a heavy man with a cloth cap. I took out my rod as it passed. In those days and nights of rations and the black-out, I wanted him to call out to me, ‘Ahoy, boy. Come aboard. And shiver me timbers.’ But he never did.

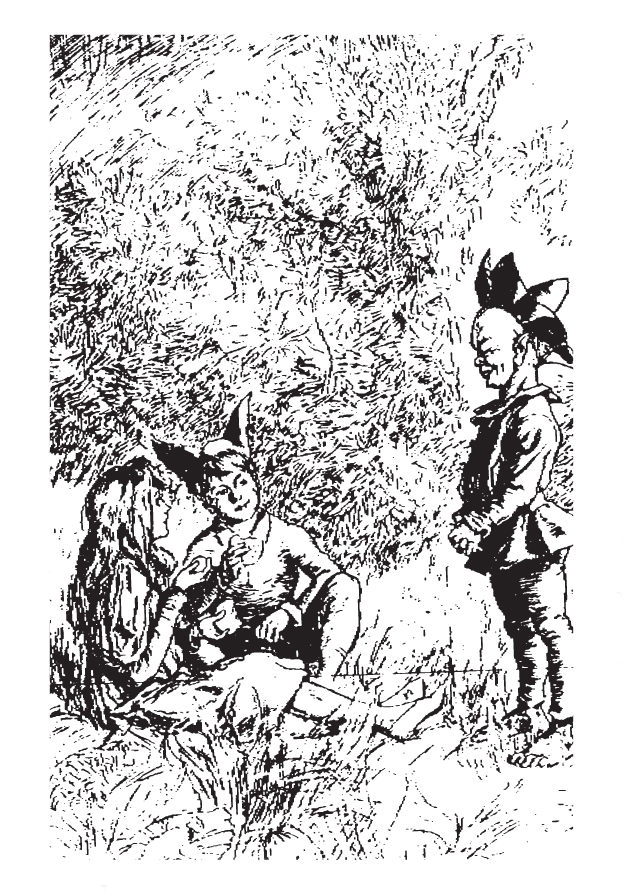

A picture in our little house and a book excited me. There was a coloured print of Sir Walter Raleigh in Elizabethan hose and doublet, sword and feathered hat, explaining his faraway adventures to two children on a beach. And there was the magic of Kipling’s Puck of Pook’s Hill, where the young brother and sister act A Midsummer Night’s Dream and meet the pixie Puck, who tells them of the people of the Hills of Old England, imps and trolls and brownies and goblins, who live by Oak, Ash and Thorn. And he relates the history of Ancient Britain in fairy story and fact.

At 8 years old, I could not tell what from which. For my sense of wonder had not left me, even in the shrapnel of war. When not watching the sparks climb in tiny fireworks on the soot at the back of the grate above the glowing coal, I read Puck of Pook’s Hill. And from the chapters on ‘Weland’s Sword’ and ‘The Knights of the Joyous Venture’, so much of my future work would unconsciously come. As Puck implied, the spell of Merlin could last a lifetime.

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inWhen I was but a boy and a bit in the last World War, I had a dream. I walked down Polstead Road in Oxford to Aristotle Lane. And I stopped off by the canal with my fishing-rod before going over the shuddering railway bridge on to the vast expanse of Port Meadow with its snapping swans. ‘Break your leg, they can,’ I was told. ‘With one chop of their beak.’

I tried to catch tiddlers, the dace and the roach, and put them in a jam-jar, though they were too muddy to eat. Sometimes a shire horse would plod up the canal path. It towed on a rope a dark barge, yet bright with painted colours, on its way to Tartary or beyond. Or so I supposed. Steering the craft, a heavy man with a cloth cap. I took out my rod as it passed. In those days and nights of rations and the black-out, I wanted him to call out to me, ‘Ahoy, boy. Come aboard. And shiver me timbers.’ But he never did. A picture in our little house and a book excited me. There was a coloured print of Sir Walter Raleigh in Elizabethan hose and doublet, sword and feathered hat, explaining his faraway adventures to two children on a beach. And there was the magic of Kipling’s Puck of Pook’s Hill, where the young brother and sister act A Midsummer Night’s Dream and meet the pixie Puck, who tells them of the people of the Hills of Old England, imps and trolls and brownies and goblins, who live by Oak, Ash and Thorn. And he relates the history of Ancient Britain in fairy story and fact. At 8 years old, I could not tell what from which. For my sense of wonder had not left me, even in the shrapnel of war. When not watching the sparks climb in tiny fireworks on the soot at the back of the grate above the glowing coal, I read Puck of Pook’s Hill. And from the chapters on ‘Weland’s Sword’ and ‘The Knights of the Joyous Venture’, so much of my future work would unconsciously come. As Puck implied, the spell of Merlin could last a lifetime. The tales the pixie told to Kipling’s children were entrancing. And there were verses, too. Puck called himself ‘the Oldest Thing in England, very much at your service – if you care to have anything to do with me’. And I did care. Country reality I found in old Hobden the hedger, who was descended from charcoal-burners. His son was a Bee Boy, not quite right in the head, but he could pick up swarms of bees in his naked hands, and take the honey from their combs. The Sword forged by Weland, smith of the gods and kin to Thor, was dark grey and wavy-lined and inscribed with runes. That weapon fell into the hands of the Norman knight Sir Richard, who fought at the battle of Hastings, where the Saxon King Harold was killed. Later, I would try to transcribe those strange signs along with the Ogham script, but then I read of the prophecies on the Sword:How marvellous and mysterious! And Sir Richard is captured by a raiding Danish ship and transported to Africa to trade beads for gold. There he fights Devils, or actually gorillas, before he returns home. Now his place is taken by Parnesius, a Centurion of the Thirtieth Legion, sent to guard the Great Wall of the North. There he struggles against the Picts, led by Allo, who was tattooed blue, green and red from his forehead to his ankles. The Wall is attacked by the Winged Hats, Norse raiders in search of booty. They are like wolves, for they come when they are not expected. The would-be Roman Emperor Maximus withdraws most of the legion to fight in Gaul, but Parnesius hangs on with his few resources, until he is relieved. Next come ‘Hal o’ the Draft’, an early scribe with a small ivory knife carved as a fish, and Master John Collins who makes the serpentines, the old ship’s cannon, for English pirates, who build churches with their loot. And then Tom Shoesmith enters from Romney Marsh, where the folk have been ‘smugglers since time everlastin’’. There lives the Widow Whitgift, a Seeker and a prophetess and a wonderful weather-tender, who loses a blind son and a dumb son to become ferrymen. The tale ends with the smugglers’ caution:A Smith makes me To betray my Man In my first fight. To gather Gold At the world’s end I am sent . . . It is not given For goods or gear But for The Thing.

Them that asks no questions isn’t told a lie. Watch the wall, my darling, while the Gentlemen go by!Finally, I found out what happened to the African gold, as the runes on the Sword had forecast. The Jewish physician Kadmiel was to promise a bribe to King John to sign Magna Carta for English liberty, before sinking the rest of the hoard. As was inscribed on the wavy blade:

The Gold I gather Comes into England Out of deep Water Like a shining Fish Then it descends Into deep Water.What a prophecy of the rise and plunge of the British Empire across the Seven Seas! And written by a man who was said to be an imperialist. To me, Kipling is rather more a mythmaker. While any have wondered at his understanding of India and its mysticism in Kim and his other tales of the Raj, his grasp of Celtic folklore has been forgotten. Yet outside Andrew Lang’s fairy tales, Puck of Pook’s Hill remains the most concise and evocative recall of the legends of Britain. Later I was to collect all of Kipling’s works in the Twenties’ Macmillan editions, bound in red leatherette and stamped with gold. My Puck of Pook’s Hill has on its outer cover an elephant’s head, clutching in its trunk a lotus petal below the sign of the swastika, the ancient Indian emblem of well-being. The illustrations are by the admirable H. R. Millar in the style of the romantic realism of the time, sketching a line of truth into a web of past fable. Another mythmaker had been a neighbour in my Oxford childhood. T. E. Lawrence was said to have written some of The Seven Pillars of Wisdom in the garden shed next door. When my brother or I hit a cricket ball over the wall and broke a window of that place which had conjured up Arabia, we did not know our sacrilege and got into trouble. But there you are. Who could believe that Polstead Road had also housed a hero of the First World War, the conflict in which Kipling had lost his son and turned to spiritualism to seek him again? When I wrote my novel Gog about the myths of Albion, I tramped over the Lothian hills from Edinburgh to York Minster in seven days with only £1 in my pocket. And sleeping on Hadrian’s Wall as the Roman sentries had, I found myself reciting the anthem of Kipling’s centurions:

I had learned the lines as a wartime schoolboy from The Dragon Book of Verse. When I visited the Orkneys and Greenland, Nova Scotia and Rhode Island, while following the voyages of the Vikings in their search for gold in America, my subsequent book The Sword and the Grail lurched in the wake of Kipling’s account of Weland’s Sword and the Winged Hats on their African adventures. It is not so much that the child is father to the man. More certain is that the books read by a child are the mother of its imagination.Mithras, God of the Morning, our trumpets waken the Wall! ‘Rome is above the Nations, but Thou art over all!’ Now as the names are answered, and the guards are marched away, Mithras, also a soldier, give us strength for the day.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 33 © Andrew Sinclair 2012

About the contributor

Andrew Sinclair has always tried to do things beyond his powers. All unreached, except for one good film and three good books. Coasting into old age, he still wonders what is to come.