I came across the book quite by chance one bitterly cold February day in the early Eighties, in a junk shop in the Brontë village of Haworth. It was a tatty copy of The Drums of Morning by Rupert Croft-Cooke, without a dust-jacket and bearing the faded sticker of the Boots Lending Library – and it launched my fascination with a writer unjustly neglected during his lifetime and now, sadly, almost forgotten.

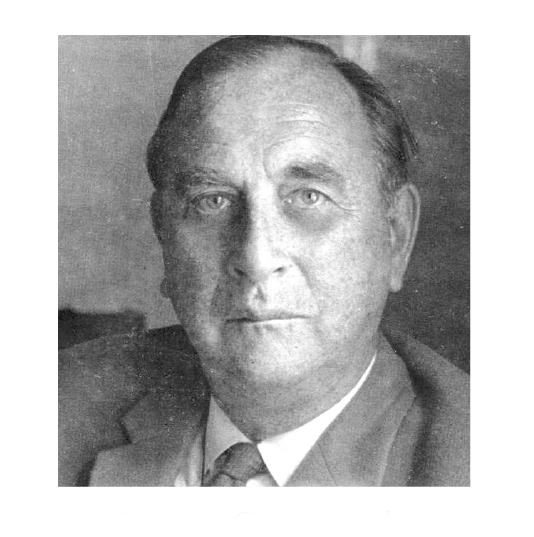

Croft-Cooke was a staggeringly prolific wordsmith, producing over thirty novels, as many detective novels under the name of Leo Bruce, and more than thirty works of non-fiction on such diverse subjects as Oscar Wilde, Kipling, Buffalo Bill, the circus, criminals, religion, gypsies, wine and cookery. His 1938 book Darts was, surprisingly, the first volume ever published on the subject. In addition, he wrote a couple of hundred short stories, as well as numerous plays and poetry, articles and essays.

But his finest work was his 27-volume autobiography, known collectively as The Sensual World. The first two books in the series, The Gardens of Camelot (1958) and The Altar in the Loft (1960), describe his birth in Edenbridge, Kent, in 1903, and his idyllic rural childhood – a brilliant evocation of the late Edwardian era swept away by the events of the Great War. The Drums of Morning (1961), the third in the series, describes his public school education, his later experiences as a teacher in Liverpool, and the events that would shape his anarchic and rebellious character in the years that followed.

As a would-be writer in my early twenties when I discovered Croft-Cooke, I found the mixture of evocative nostalgia for the longgone post-Great War era, and his burning passion for literature and desire to become a writer, quite apart from his altruistic world-view, utterly compelling. Over the course of the next few years I managed to track down the remaining volumes of The Sensual World, br

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI came across the book quite by chance one bitterly cold February day in the early Eighties, in a junk shop in the Brontë village of Haworth. It was a tatty copy of The Drums of Morning by Rupert Croft-Cooke, without a dust-jacket and bearing the faded sticker of the Boots Lending Library – and it launched my fascination with a writer unjustly neglected during his lifetime and now, sadly, almost forgotten.

Croft-Cooke was a staggeringly prolific wordsmith, producing over thirty novels, as many detective novels under the name of Leo Bruce, and more than thirty works of non-fiction on such diverse subjects as Oscar Wilde, Kipling, Buffalo Bill, the circus, criminals, religion, gypsies, wine and cookery. His 1938 book Darts was, surprisingly, the first volume ever published on the subject. In addition, he wrote a couple of hundred short stories, as well as numerous plays and poetry, articles and essays. But his finest work was his 27-volume autobiography, known collectively as The Sensual World. The first two books in the series, The Gardens of Camelot (1958) and The Altar in the Loft (1960), describe his birth in Edenbridge, Kent, in 1903, and his idyllic rural childhood – a brilliant evocation of the late Edwardian era swept away by the events of the Great War. The Drums of Morning (1961), the third in the series, describes his public school education, his later experiences as a teacher in Liverpool, and the events that would shape his anarchic and rebellious character in the years that followed. As a would-be writer in my early twenties when I discovered Croft-Cooke, I found the mixture of evocative nostalgia for the longgone post-Great War era, and his burning passion for literature and desire to become a writer, quite apart from his altruistic world-view, utterly compelling. Over the course of the next few years I managed to track down the remaining volumes of The Sensual World, brought out by a total of nine different publishers between 1937 and 1977. I followed Croft-Cooke’s travels and travails as he taught in Argentina in the Twenties, then supplemented his meagre writer’s income by running a bookshop and teaching, while living precariously in London, Kent, Sussex, Cornwall, the Cotswolds and Switzerland. In the Thirties he spent months travelling with gypsies and with Rosaire’s circus, experiences which found their way into The Moon in My Pocket (1948) and The Circus Has No Home (1951). In the winter of 1937 he motored around Europe in a converted Morris-Commercial bus, collecting material for The Man in Europe Street, a topical book which endeavoured to gauge the mood of a continent moving headlong towards conflict. During the Second World War he served with Field Security in Madagascar and India, and from the early Fifties lived in Tangier for fifteen years. Croft-Cooke wrote of his hopes as a writer:In all my life, I realise now, I have had two single aims which become one when I write. I have wanted to love people, not only – perhaps not chiefly – of my own race and background, but people of strange callings, of other countries and languages, people antithetical to my family and natural associates. Then to identify with them, to try and be mistaken for one of them, to learn their languages, share their points of view and, where they have been outcast, to be an outcast with them.He was a nonconformist, an eternal optimist, and eternally interested in new and varied experiences. The autobiographies bristle with incident and loving accounts of the personalities, famous and otherwise, he encountered during his varied and peripatetic life. The list of writers he met reads like a roll-call of the literary greats of yesteryear: while still a teenager he made a pilgrimage to visit his heroes Rudyard Kipling and John Masefield; in his twenties he met G. K. Chesterton, who encouraged his literary endeavours. He later became close friends with Compton Mackenzie and the pre-war best-seller Louis Golding, who recurs in his story as a larger-than-life figure combining egocentricity and buffoonery. For all that Golding was a figure of fun in literary circles of the time, however, the portrait of him never descends to ridicule – and this is indicative of Croft-Cooke’s attitude to life in general. His writing is remarkable for its even-tempered tone and good humour. He never resorts to acerbity, and even when events go against him he maintains a wry sense of proportion. He seems incapable of rancour, and was proud of his ability to make the best of any set-back or mishap. And it was a life not without hardship. His struggle to make a living often forced him to produce quickly written and second-rate work, and to take on menial and sensational journalism. In the Thirties he was tied to an iniquitous contract by Walter Hutchinson, and compelled to write five books a year in order to repay the publisher’s expense of having to pulp his fourth novel Cosmopolis (reprinted in 1949 as The White Mountain) after libel action was threatened by the Swiss headmaster of the school at which Croft-Cooke had worked and which he used as the setting for the book. Although the memoirs do reveal his character, there is one aspect of himself that he was loath to air in public. Croft-Cooke was homosexual when male homosexuality was illegal. He was over 60 when the act was eventually decriminalized in 1967, and accustomed to a lifetime of keeping the fact of his sexuality out of his writings. Even after ’67 he found it hard to admit in print, instead making veiled hints in later autobiographies. Croft-Cooke stated often in the course of The Sensual World that the books were not about himself but that his aim was to record accurately a passing era. It is tempting to speculate how much more accurate, not to mention sensual, that record might have been had circumstances allowed him to write openly of his most intimate feelings and experiences. In 1943, while serving as a Field Security Officer in India, Croft-Cooke met a 17-year-old Indian, Joseph Sussainathan. The writer was then 40. They remained together, Sussainathan employed as Croft-Cooke’s secretary, for the next thirty-six years. In his 1965 travel-cum-autobiographical volume about India, The Gorgeous East, Croft-Cooke describes their meeting in perfunctory terms, glossing over not only how he managed to employ Sussainathan as his aide throughout his service in India, but also their true relationship. His partner features only fleetingly in the remaining books in the series, their relationship referred to as resembling that between father and son. In 1953 Croft-Cooke was jailed for six months, and Sussainathan for three months, on a charge of homosexual indecency. They were found guilty of inviting two sailors back to Croft-Cooke’s Ticehurst home and over the course of a weekend indulging in homosexual practices. In ’54 Croft-Cooke published a book about the court case and his time in Wormwood Scrubs and Brixton. The Verdict of You All is a searing indictment of conditions in British jails in the Fifties and a diatribe against the miscarriage of justice that brought about the sentencing. Perhaps more remarkable, though, is the fact that Croft-Cooke manages throughout the course of the book to deflect the question of whether or not he is in fact homosexual. On his release from jail he settled in Tangier, where over the next fifteen years he wrote much of his best work, including perhaps his finest novel, Seven Thunders, which graphically details the German destruction of the ancient Vieux Port area of Marseilles in 1943. It was over twenty years before I reread The Sensual World series, and then not without a sense of trepidation. I feared that my own youthful penchant for romance, my desire to share the struggle of a fellow aspiring writer, might have coloured my view. I need not have worried. The Sensual World comes across, even after multiple rereadings, as a loving and wondrous account of a life lived to the full. Croft-Cooke’s avowed aim was to leave behind a comprehensive record of his times, and in this he succeeded. He died in Bournemouth in 1979, at the age of 75, leaving an oeuvre of over a hundred books, none of which is now in print. The best of his novels may indeed be unjustly neglected – but it is The Sensual World series which deserves to find a new audience, and which will be seen as Croft-Cooke’s lasting legacy to the world of English letters.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 27 © Eric Brown 2010

About the contributor

Eric Brown is the author of over thirty books for adults and children, and more than a hundred short stories. He also writes a regular science fiction review column for the Guardian.