It is a universal truth that those in the creative professions will always be patronized by those who don’t and can’t create. ‘Resting?’ they will enquire of the out-of-work actor, with a tilt of the head and an upward inflexion, certain of an affirmative reply. An artist of my acquaintance was once asked what colour his interrogator should decorate her hall, as if he were merely a walking Dulux paint chart. Pity, then, the jobbing writer. ‘Still scribbling?’ is what he or she hears from those who insist that they would ‘put pen to paper’ some day or get that half-finished novel in the sock drawer published for certain, if only they had the time.

Time, for Blake’s sunflower and for the writer with deadlines, is, of course, a wearying issue. If only it were possible to visit some parallel universe, write copy there, and return to one’s own world at exactly the same moment as when one left it. There is such a country – imaginary, alas – where time passes but stays the same in our normal existence. On the edge of it we stand, like Miranda, in awe of the wonders of this brave new world; as adults we are too old to be allowed to enter it, but our children may. It is called Narnia. A. N. Wilson’s splendid biography of C. S. Lewis – recently reissued, for which much thanks – is subtitled ‘The classic life of the author who created Narnia’; like A. A. Milne, Lewis is chiefly remembered for a tiny part of his oeuvre. Wilson writes that Lewis ‘was addicted to . . . answering all the letters . . . sent to him . . . often rising a good while before daybreak’ to undertake this monumental task.

Surely even Lewis, despite his phenomenal output, must have wished occasionally that time would stand still. He does seem an unlikely candidate for iconic status. Certainly he never pursued fame, preferring to live quietly in Oxford and then Cambridge, always with his elder brother Warnie (so beautifully played by Edward

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIt is a universal truth that those in the creative professions will always be patronized by those who don’t and can’t create. ‘Resting?’ they will enquire of the out-of-work actor, with a tilt of the head and an upward inflexion, certain of an affirmative reply. An artist of my acquaintance was once asked what colour his interrogator should decorate her hall, as if he were merely a walking Dulux paint chart. Pity, then, the jobbing writer. ‘Still scribbling?’ is what he or she hears from those who insist that they would ‘put pen to paper’ some day or get that half-finished novel in the sock drawer published for certain, if only they had the time.

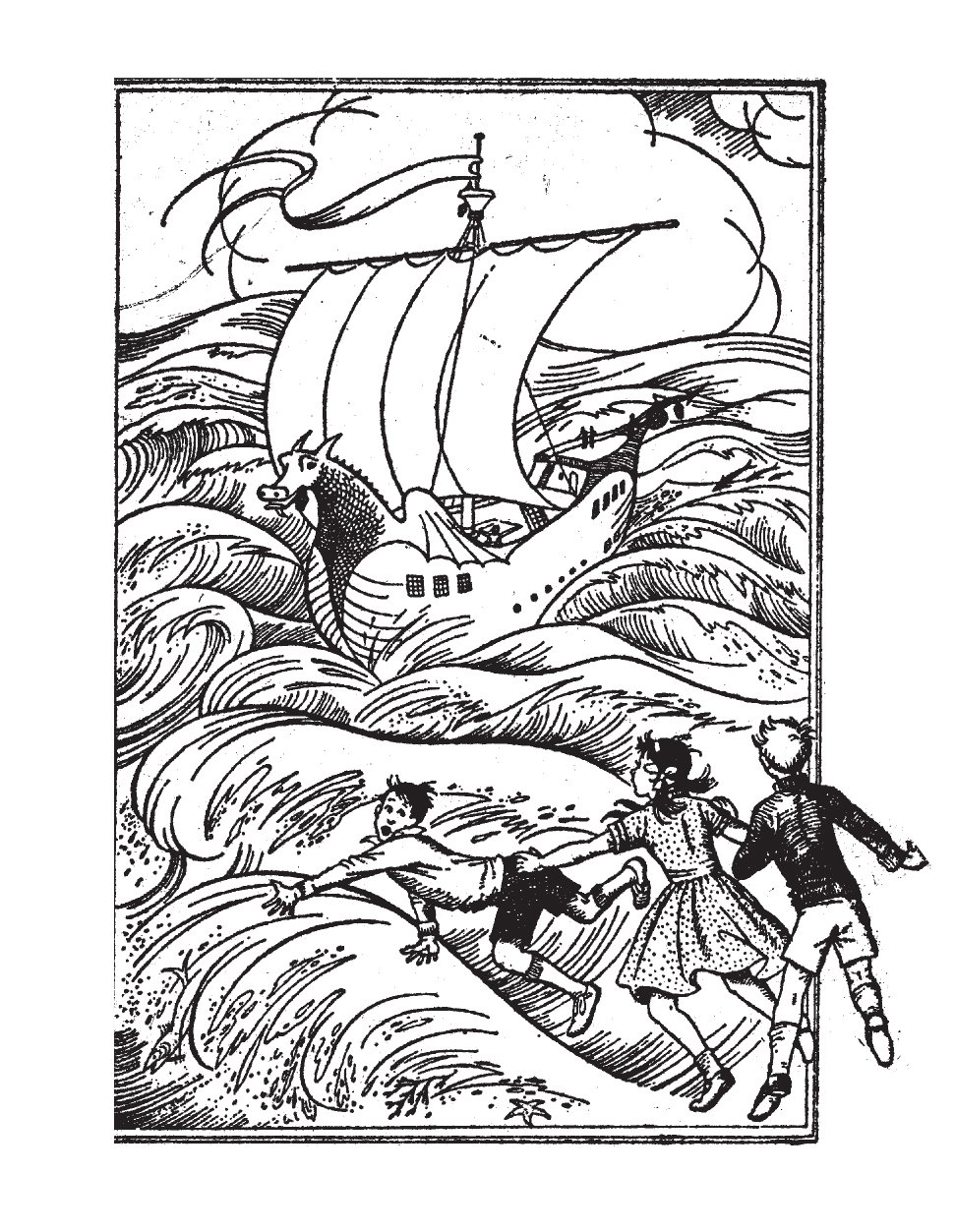

Time, for Blake’s sunflower and for the writer with deadlines, is, of course, a wearying issue. If only it were possible to visit some parallel universe, write copy there, and return to one’s own world at exactly the same moment as when one left it. There is such a country – imaginary, alas – where time passes but stays the same in our normal existence. On the edge of it we stand, like Miranda, in awe of the wonders of this brave new world; as adults we are too old to be allowed to enter it, but our children may. It is called Narnia. A. N. Wilson’s splendid biography of C. S. Lewis – recently reissued, for which much thanks – is subtitled ‘The classic life of the author who created Narnia’; like A. A. Milne, Lewis is chiefly remembered for a tiny part of his oeuvre. Wilson writes that Lewis ‘was addicted to . . . answering all the letters . . . sent to him . . . often rising a good while before daybreak’ to undertake this monumental task. Surely even Lewis, despite his phenomenal output, must have wished occasionally that time would stand still. He does seem an unlikely candidate for iconic status. Certainly he never pursued fame, preferring to live quietly in Oxford and then Cambridge, always with his elder brother Warnie (so beautifully played by Edward Hardwicke in the film Shadowlands), and in the company of like-minded men who thrived on argument, beer and tobacco. Lewis himself in his later years has been much depicted on stage and screen, but his children’s books, like J. R. R. Tolkien’s, are set to become known to an even wider audience through the medium of film. A trinity of discoveries led me back to Narnia. Just before I was given the Wilson biography to review, I found at the back of a cupboard (not, alas, a wardrobe) the 1964 hardback edition of one of the lesser-known of the chronicles – The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. And a copy of Lewis’s autobiography, Surprised by Joy, had recently fallen into my hands, rather appropriately, off the second-hand bookstall at a church jumble sale. It is a charming book, very much of its time, with a distinct air of nineteenth-century authorial circumspection. The child-self Lewis depicts in his autobiography seemed suddenly very familiar. Here was a precocious, solitary boy, virtually an only child (his brother away at school), ‘showing off ’ to grown-ups by using ‘bookish language’. Lewis is tough on himself, but he does seem to have shared some of the less palatable characteristics of a child in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader – the anti-hero, Eustace Clarence Scrubb. Beastly name. Horrid boy. I once knew someone exactly like him – boastful and bossy – who enthralled me with his metropolitan insouciance. Like Eustace, he called his parents by their Christian names – undreamed-of sophistication in the early 1960s when, even fifty miles from the capital, one could be (and was) totally oblivious to Swinging London. I cross-referenced, checked and checked again. Yes, there was Eustace being magicked, with his cousins Lucy and Edmund, on to a Narnian ship at the start of the adventure, a ‘prodigal who is brought in kicking, struggling, resentful, and darting his eyes in every direction for a chance to escape’. This is exactly how Lewis described his own feelings in Surprised by Joy, before he finally ‘gave in and admitted that God was God’. There are references in all the Narnia books to the early influences and experiences that shaped Lewis. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe has the house with many rooms owned by the kindly, scholarly Professor Kirke, which matches a description of the Belfast home in which Lewis grew up. The Magician’s Nephew contains a direct crib from E. Nesbit’s The Story of the Amulet – a foreign queen’s visit to Victorian London. Lewis in Surprised by Joy acknowledges his life-long devotion to the works of Nesbit, the Amulet being his favourite. There is also a poignant image of a sick mother, adored by her son Digory, the boy who witnesses the creation of Narnia, and who grows up to become the Professor. Lewis’s own mother died when he was a child, at about the age he makes Digory. In the story, Mother lives, saved by eating an apple from a Narnian tree, a seed from which is planted. When the tree that grows from it eventually falls, it is made into a wardrobe. Through this, Lucy, in the first book, discovers Narnia. Lewis read voraciously, in a house full of books. In nursery days he favoured Beatrix Potter, E. Nesbit and Swift’s Gulliver, and when he wasn’t reading, he made up elaborate games, in the company of Warnie. Early stories had combined ‘two chief literary pleasures, dressed animals and knights in armour’. From those came a ‘medieval Animal Land’ which was combined with Warnie’s stolid invention, in his part of the game, of a completely modern imaginary land. ‘Soon there was a whole world . . . in mapping and chronicling [it] I was training myself to be a novelist.’ From his childhood, Lewis had the template with which to create Narnia. ‘All the fiction I could get about the ancient world’ followed: Longfellow’s poetry, H. G. Wells and Rider Haggard, Matthew Arnold’s Sorhab and Rustum, and then, galloping into view, trailing clouds of glory that coincided with a new and ecstatic feeling of ‘Northernness,’ came Wagner and the Norse legends. These had a profound effect on Lewis, as, slightly later, did the allegorical fantasies of George MacDonald; and, whilst being tutored prior to Oxford, Lewis also discovered The Odyssey, Milton, Spenser, Voltaire, Malory and William Morris, amongst many others. The third Narnia book, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, is, of all of them, the closest to Lewis’s early life in its content, but it is the least ‘Narnian’ in that it takes place entirely outside the legendary country itself. It begins with a Homeric quest – to discover the fates of seven Narnian lords – a voyage made in what looks like a Viking long-ship, peopled by chivalrous men. One of the most memorable crew-members is Reepicheep, a talking mouse, straight out of Dumas, whose ambition is to find ‘Aslan’s country’ and Aslan the lion himself, creator of Narnia. In a nod to the Ring cycle, Eustace, like Fafner the giant in Die Walküre, turns into a dragon on one of the islands discovered on the journey, and learns a bitter lesson. Lewis’s childish terror of insects is revisited when the ship passes a nameless island where dreams come true. The last island the travellers find is reminiscent of the land of the midnight sun. Its inhabitants, an ancient star and his daughter, are surely residents of Pliny’s Ultima Thule, the furthest northern point of the ancient world, and the three remaining Lords sleeping there a combination of Christian legend and secular myth. Paddling to the edge of Paradise, passing through significant piles of water lilies (which symbolize, in flower language, purity of heart), the mouse fulfils his destiny by going on into Aslan’s country alone, and the children are sent back into their own world. Eustace does return to Narnia in later books, notably The Silver Chair, with its wonderful underground sequence, its giants and bewitchment (more Wagnerian elements), and of course in The Last Battle, where Narnia is destroyed by Aslan and recreated, as it was made, in one day. It is telling that the quest was for seven lords in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. Seven is a significantly Christian number (the Lord’s Prayer is divided into seven sections, the Creation took seven days), and after all, Lewis was very devout. There are also seven Narnia books. He once said of them ‘I wrote the books I would like to read’, and if only tempus didn’t fugit quite so much, I would extol every single one of the chronicles.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 12 © Sarah Crowden 2006

About the contributor

In her parallel universe, Sarah Crowden would like to be a member of the Garrick Club.