Why did I always detest The Wizard of Oz so? The film, with its songs and vivid colours, isn’t so terrible, is it? You can see it every Christmas on TV even now, seventy and more years after it was made. Everyone loves it. ‘Perennial favourite’, they call it.

I was given the book for my birthday or Christmas in 1947 when I was 4, and it was read to me sometime afterwards, perhaps even after March 1948 when the Good Friday Tornado, as it is still called, hit our small town in Indiana.

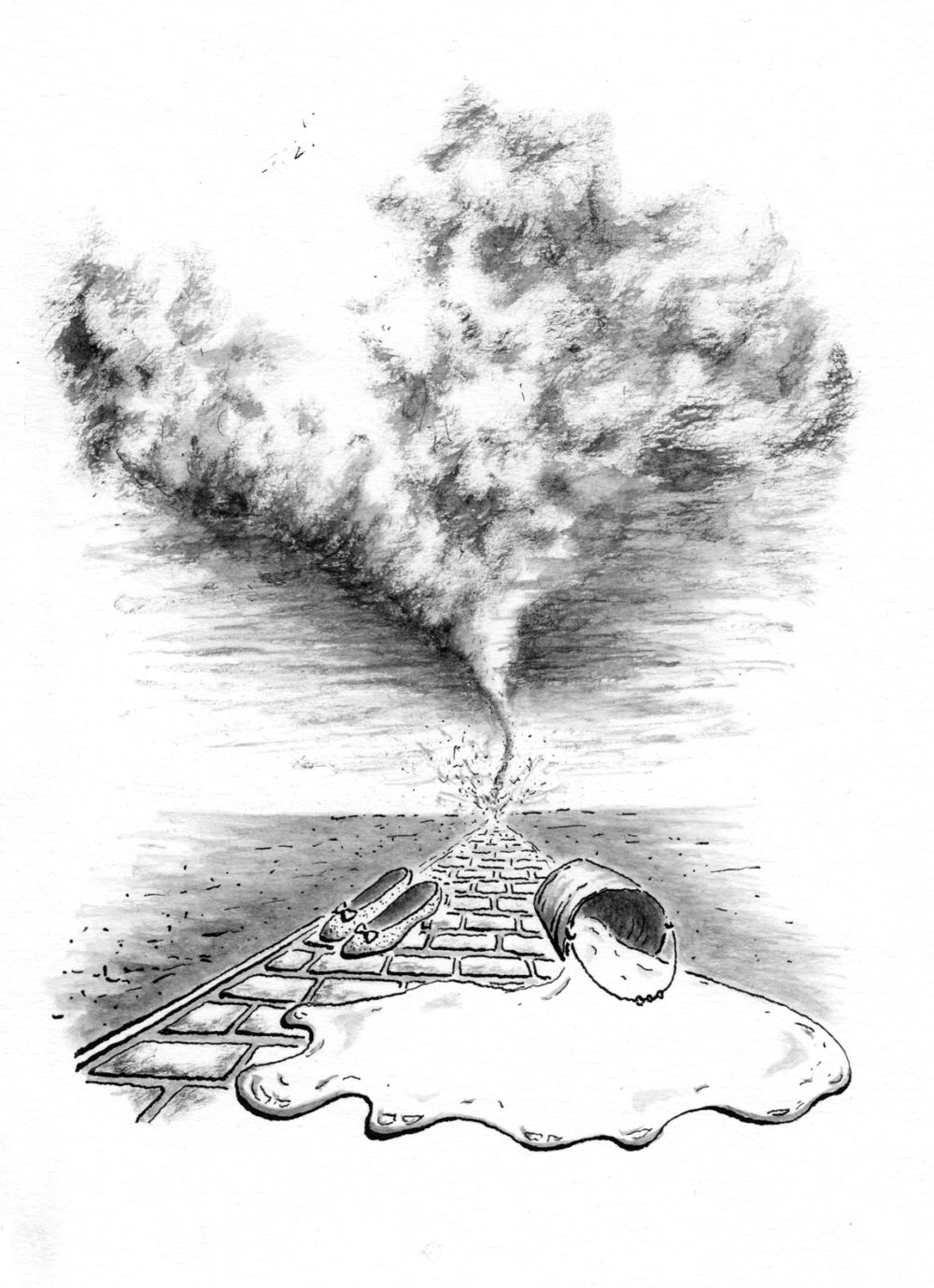

Everything was wrong with the book. First and worst was the tornado that whirls Dorothy and the house up and away from Kansas and her Aunt Em and Uncle Henry. Even as a little pre-schooler who couldn’t cross the street by myself, I knew that tornadoes were extremely dangerous and if you were blown away by one you were not greeted by kindly Munchkins with bells on their hats. If you were outside during a tornado you simply disappeared and were never seen again, like the Williamson boy in our town.

Then there was the Scarecrow who was made entirely of straw. Imagine scratching your head and encountering only straw. The horror of it! And the Tin Woodman alarmed me. Until Dorothy fetches the oilcan, he is rusted so badly that he is stuck in one position, like the severely arthritic old man who went to my grandparents’ church and had to be lifted into and out of a car because his hips and legs were rigid right angles.

So I hated The Wizard of Oz with its terrifying tornado and its revolting characters. I once looked up a biography of the author, L. Frank Baum, and discovered, exactly as I had suspected, that he was born and grew up in New York State and not in the tornado-prone Mid-West. It figured. He had never been a small child watching a spring afternoon become a howling midnight and then afterwards, when th

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inWhy did I always detest The Wizard of Oz so? The film, with its songs and vivid colours, isn’t so terrible, is it? You can see it every Christmas on TV even now, seventy and more years after it was made. Everyone loves it. ‘Perennial favourite’, they call it.

I was given the book for my birthday or Christmas in 1947 when I was 4, and it was read to me sometime afterwards, perhaps even after March 1948 when the Good Friday Tornado, as it is still called, hit our small town in Indiana. Everything was wrong with the book. First and worst was the tornado that whirls Dorothy and the house up and away from Kansas and her Aunt Em and Uncle Henry. Even as a little pre-schooler who couldn’t cross the street by myself, I knew that tornadoes were extremely dangerous and if you were blown away by one you were not greeted by kindly Munchkins with bells on their hats. If you were outside during a tornado you simply disappeared and were never seen again, like the Williamson boy in our town. Then there was the Scarecrow who was made entirely of straw. Imagine scratching your head and encountering only straw. The horror of it! And the Tin Woodman alarmed me. Until Dorothy fetches the oilcan, he is rusted so badly that he is stuck in one position, like the severely arthritic old man who went to my grandparents’ church and had to be lifted into and out of a car because his hips and legs were rigid right angles. So I hated The Wizard of Oz with its terrifying tornado and its revolting characters. I once looked up a biography of the author, L. Frank Baum, and discovered, exactly as I had suspected, that he was born and grew up in New York State and not in the tornado-prone Mid-West. It figured. He had never been a small child watching a spring afternoon become a howling midnight and then afterwards, when the day came back, seeing big maples lying across the street like rungs of a ladder and the side of a solid brick mansion blown out, the rooms exposed like a doll’s house. However, you can’t go through life clinging to a judgement you made at the age of 4. When I unearthed that old copy of The Wizard of Oz, its endpapers a collage of stills from the recent film, I felt a moral obligation to read it. I had never read it on my own. My only experience of it had come to me from my mother’s voice as I sat on her lap in an easy chair. Now I read it with an open mind and even declaimed some passages aloud so as to recreate the experience of hearing the words. I thought of children hearing it when it first appeared and I put the film out of my mind. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was first published in 1900, and Baum wrote in a short introduction that he specifically wanted to get away from the ‘old-time fairy tale’ and substitute ‘a series of newer “wonder tales” in which the stereotyped genie, dwarf and fairy are eliminated, together with all the horrible and blood-curdling incidents devised by their authors to point a fearsome moral to each tale’. He wanted only to please modern children, he said, and so his Wonderful Wizard of Oz ‘aspires to being a modernized fairy tale, in which the wonderment and joy are retained and the heart-aches and nightmares are left out’. For all that, the old trappings are still there. The pages aren’t even into double figures when we encounter a witch, and before long there are forests straight out of the Brothers Grimm, and walled cities, castles and kings. You might think that someone writing in a proud Republic in 1900 might have found some substitute for castles and kings, but then again, perhaps they are fixed ingredients of any fairy tale, modernized or not. Would the Munchkins have regular elections and a representative legislature? I doubt it. When Dorothy is whirled off by the tornado she lands in the Munchkin district of Oz, which is ruled by the Wicked Witch of the East. She is greeted by the diminutive Munchkins and the Witch of the North, who explains that in Oz the witches of the North and South are good, whereas the witches of the East and West are wicked. Dorothy has just won everyone’s devotion because she has done away with their Wicked Witch for them: her house has landed squarely on the witch, leaving only her legs (which soon shrivel and disappear) and her silver shoes protruding from under it. These magic shoes are presented to Dorothy, although no one knows quite what is magic about them. They are a perfect fit, of course. Dorothy wants only to get back home to Kansas and so the kindly Witch of the North explains that she must journey to the Emerald City, far away in the middle of Oz, to ask this favour of the Wizard. Dorothy will be protected by the northern witch’s indelible kiss on her forehead. The Witch of the North and the grateful Munchkins start her on her way following the Yellow Brick Road, which leads to the Emerald City. As she goes along she soon accumulates three companions who also long for something: a brain (the Scarecrow), a heart (the Tin Woodman), and courage (the cowardly Lion). She rescues the Scarecrow from his post; she revives the Tin Woodman by oiling his rusted joints; and when the Lion jumps out at them, pretending to be ferocious, Dorothy rebukes him and he admits to being a coward. The four journey through deep forests and past obstacles until eventually they reach the Emerald City and gain an audience with the Wizard, who sets Dorothy yet another task. Death is in queasy evidence in The Wizard of Oz, but often with a tongue-in-cheek wink. Dorothy’s task of killing the Wicked Witch of the West is made only slightly less disturbing when the Wizard tells her, ‘Remember that the Witch is Wicked – tremendously Wicked – and ought to be killed.’ Dorothy has been captured and put to work in the Witch’s kitchen. The Witch tries to steal one of Dorothy’s silver shoes, and Dorothy, in an uncharacteristic access of anger, sloshes a bucket of water over her. The Witch begins to dissolve because, for all her power and Wickedness (with a capital W), she is water-soluble. Dorothy slings another bucket over the old tyrant for good measure and then tidies up the drenched floor and late witch. The Emerald City and the Wizard turn out to be a sham. Everyone entering the city is made to wear green glasses locked in place with a key so that everything will appear to be green. On the travellers’ second meeting with the Wizard he is revealed to be an ordinary man behind a screen who has adopted various ruses to fool people; he is, among other things, a ventriloquist and a master of disguises. He hands out the brain (bran with pins and needles mixed in, so that the Scarecrow will be ‘sharp’), the heart (a sort of silk pin cushion fixed in the Tin Woodman’s chest), and courage (a potion the Lion must drink, because courage lies in the stomach). Getting Dorothy back home is more problematic – the solution of a hot-air balloon fails. In fact, the silver shoes, acquired from the unfortunate Wicked Witch of the East, are the answer because they turn out to be Seven League Boots in spades. Reading the story now, I notice a few things that escaped me at the age of 4, like the Swiftian encounters with strange civilizations and the odd parallels with Alice, who falls down a hole instead of going up in a funnel. The whole story is almost a parody of the traditional fairy tale. Dorothy rescues the Woodman instead of the other way round. The brainless Scarecrow is in fact rather clever. Frightening would-be ogres are hollow men. It is interesting too that the Wicked Witch of the West specializes in enslaving the unwary – this in a book published only 35 years after the end of the Civil War. While the East and West Witches provide the necessary shudders, the Witches of the North and South are both good. I doubt if these compass points were accidental. There is even a proto-feminist touch in a girl as hero, and one who isn’t looking for a handsome prince; Dorothy just wants to get home to Uncle Henry and Aunt Em in Kansas. Dorothy is no passive Rapunzel; she pursues her quest, battles adversity, achieves her aim and helps her friends achieve theirs. Is it dated? Not as much as you might think, for we are in that fairytale world where people wear timeless clothing and do timeless things, including, in Dorothy’s case, finding comfortable places to sleep and having regular breakfasts. I have never met anyone else who loathed The Wizard of Oz, and now I can at last join the majority, because to my surprise I have come to admire it. It is a good thing, after all, to be an ex-loather, to slosh a bucket of water on your detestation and find it melting into the floor.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 39 © Sarah Lawson 2013

About the contributor

Sarah Lawson escaped tornadoes by moving to London; she now writes and translates from the safety of a house that has yet to leave the ground. Besides writing her own poetry (All the Tea in China) she has translated selected poems by Jacques Prévert.