Desperation drove me to Horatius, one gloomy afternoon in late October. Thirty restless children were waiting to be entertained, educated or even just dissuaded from rioting by their hapless supply teacher. I gave them Macaulay’s Lays of Ancient Rome – largely because my father’s recitation of ‘How Horatius Kept the Bridge’ had so grabbed and held my own attention, decades earlier. The drama of the thing still worked its magic: the bridge fell with a crash like thunder, whereupon ‘a long shout of triumph rose from the walls of Rome / As to the highest turret-tops was splashed the yellow foam’. My father would put gleeful stress on the word ‘yellow’. Then, of course, brave Horatius, fully armed and uttering a powerful prayer to Father Tiber, hurls himself into the turbulent river and makes it to the other shore.

It was but a short step to the writings of Rosemary Sutcliff. For a bookish child, discovering more about the ancient world in which she was so at home was unadulterated pleasure. Her Romans became more immediate, fallible, brave, attractive and alarming than anyone I ever encountered in outer Surrey. Reading her, history came brilliantly and noisily to life, and was to remain a lasting passion for all of us who came under her spell, which I’d bet includes half the life-members of the National Trust.

You could also bet that she knew her Macaulay. Towards the end of Frontier Wolf, young Alexios, now wearing the emerald dolphin ring of the Aquila family, is leading his weary and wounded troops at speed, away from their indefensible fort on the Firth of Forth. They are a mixed bag, few with more than a tenuous connection to Rome, but they have developed a personal loyalty to Alexios, and are on his side. To have any chance of escaping their pursuers, they must destroy the bridge on the road to Bremenium. The men work furiously with axes, crowbars and ropes, some waist-deep in icy water, leaving only a few to stand and fight off the vengeful tribal armies until, when it seems almost impossible, ‘there was a whining and cracking of timbers, and, with a rending crash the whole thing keeled over, and its centre and near end swept downriver in a tossing welter of beams and planking’.

But Lucius, a learned, avuncular officer whom we have come to love, is mortally wounded. Immediately, the focus narrows until we are alone with him, and Alexios comforting him:

‘You’ve had a hard morning’s work. Go to sleep now.’

And like a tired child, he turned his head on Alexios’s knee and settled his cheek. He gave a small, dry cough, and that was all.

It was like Lucius, his Commanding Officer thought, to die so quietly and neatly.

It takes a great writer to zoom in from the furious heat and clangour of battle to such a tender moment and then, heaving a deep sigh, to send the tattered remnants of an exhausted army further south, into the leaden dawn, towards the safety of the Wall.

It is the year 343, and the effete Emperor Constans, visiting Britain, offers Alexios another command, well away from the inhospitable north. He spends a moment looking back on it all, on ‘the hills of his lost wilderness’ where many previously strong Roman forts now lie abandoned, where he had grown to maturity, and where he knows that he will never walk again.

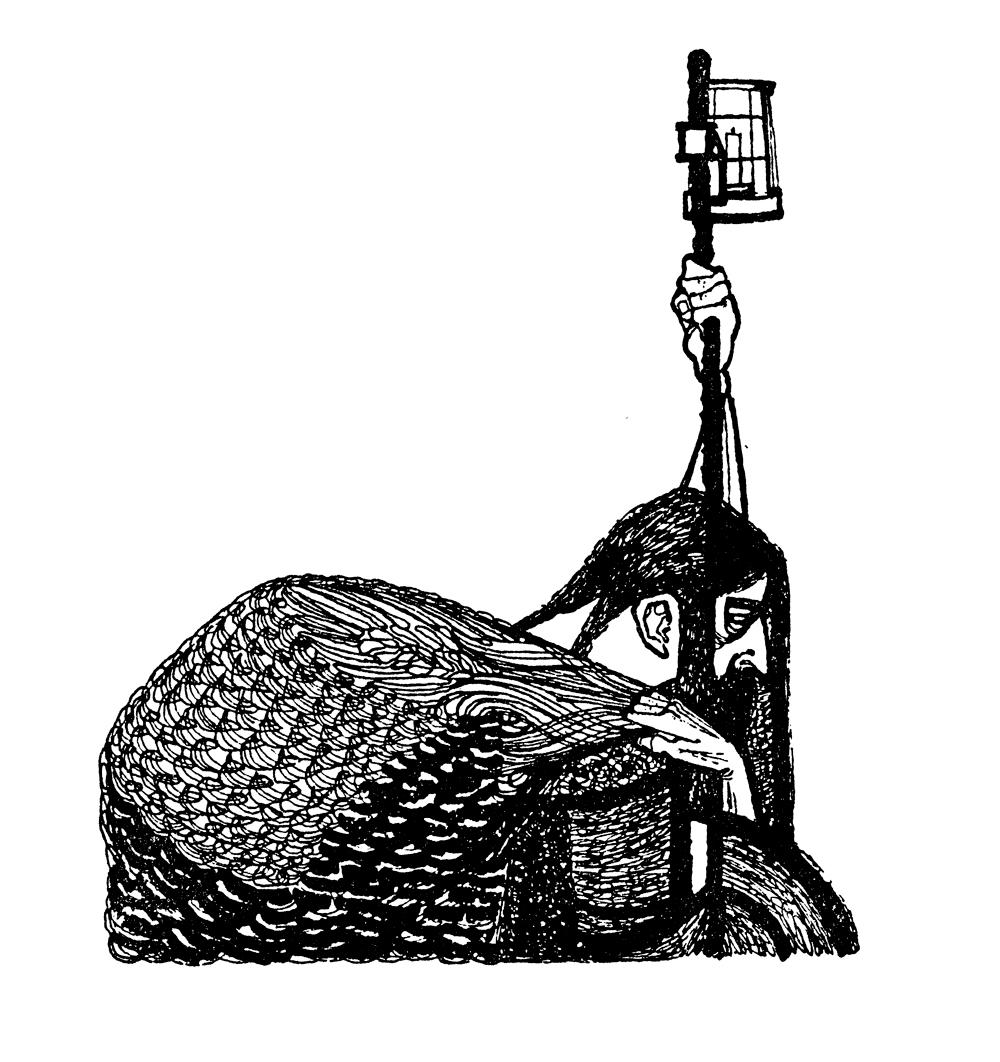

In The Lantern Bearers, set a century later, it is the old, blind Flavian, a descendant of Alexios, who now wears the dolphin ring. His son Aquila, like his ancestors, marches with the legions, but as soon as he arrives home on leave he is ordered back to port, for by now the Romans are finally abandoning Britain. In a moment of crisis he decides that, despite deeply divided loyalties, his place is with his family, rooted through generations in their old farm in the gentle South Downs. He deserts from the army – just in time to see the farm razed to the ground, his father killed and his sister carried off by Saxon Sea-Wolves. As the Dark Ages close in, Aquila gradually learns that he must become one of the lantern bearers: the physician Eugenus explains that it is ‘for us to keep something burning, to carry what light we can forward into the darkness and the wind’.

Aquila’s adventures take him into slavery in Viking galleys, land him on the northern shores of Scandinavia and eventually bring him back to Kent, to Tanatus or the Isle of Thanet, the ‘great burg of Hengist’, where he manages to regain his freedom and eventually to become a married man, a father, an uncle and, once again, a soldier, though by now Rome is long gone and he is fighting for the Britons.

His own fateful bridge is across the Medway at Durobrivae, now Rochester. This time he is himself one of the little band defending it against Hengist’s ferocious advance-guard, those blue-eyed snarling Saxons who had burned his home and killed his father. And it is he who, like Horatius, springs with a shout of triumph into the ‘immensity of nothingness opening behind him . . . and the cold water . . . engulfed him and closed over his head’.

These are tremendous stories, superbly written, thrilling and profound. In each novel, the central character learns to respect, value and even to love people with no blood connection with Rome – or indeed with himself. And each of them overcomes a burden of prejudice: Alexios has been condemned for abandoning a fort that could (perhaps) have been saved, while Aquila cannot conquer his hunger for revenge. Ultimately, Alexios is forced to evacuate another fort, and is this time applauded, though the major tragedy of his young life has been losing his dearest friend. And young Aquila realizes that he must finally put aside his pride and adopt the principles and customs of the native people of Britain, for whom Rome is becoming an increasingly distant memory, as her vast, unruly empire slowly vanishes into the mists.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 67 © Sue Gaisford 2020

About the contributor

Sue Gaisford is an all-purpose journalist, currently trying hard to control and obsession with Roman remains, but reluctant to plunge too deeply into the Dark Ages.