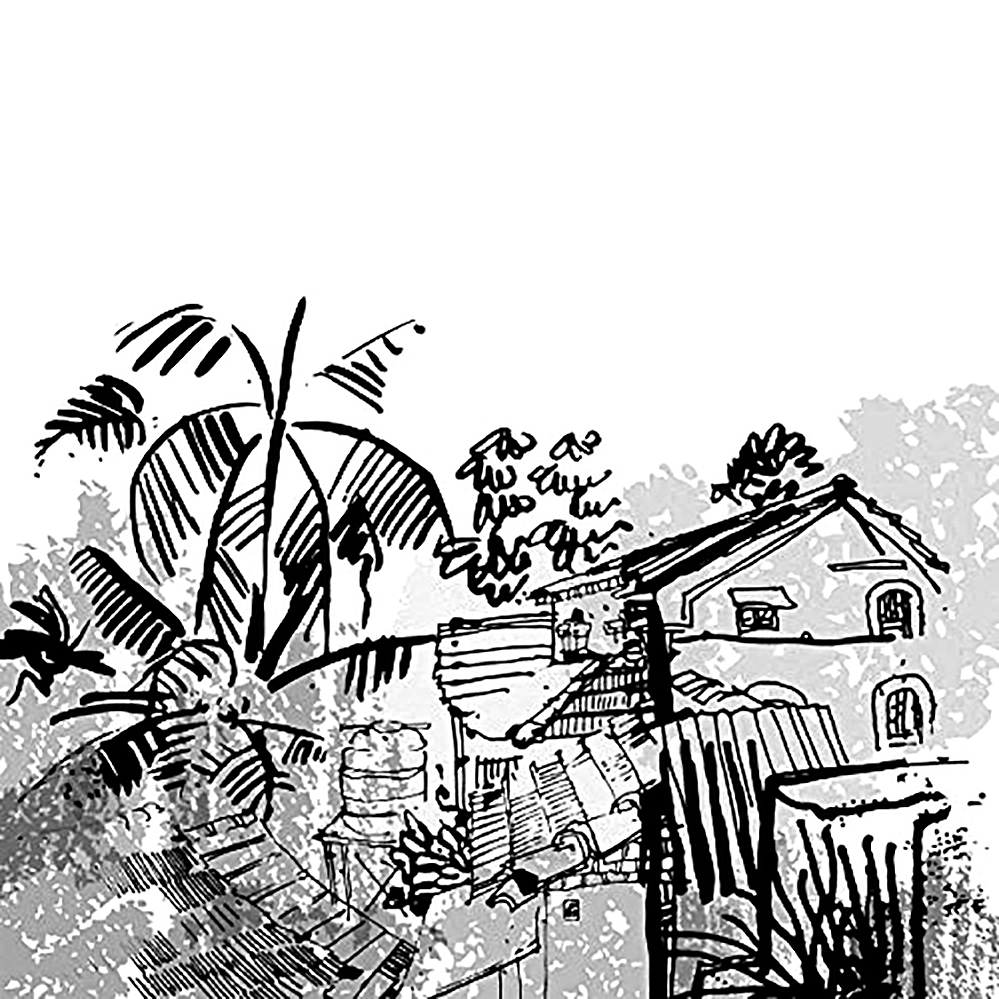

He had thought deeply about this house, and knew exactly what he wanted. He wanted, in the first place, a real house, made with real materials. He didn’t want mud for walls, earth for floor, tree branches for rafters and grass for roof. He wanted wooden walls, all tongue-and-groove. He wanted a galvanised roof and a wooden ceiling . . . The kitchen would be a shed in the yard; a neat shed, connected to the house by a covered way. And his house would be painted. The roof would be red, the outside walls ochre and the windows white.

A House for Mr Biswas was my lockdown book. As cases of Covid climbed, and the loveliest spring was filled with fear, I took myself back to the first half of the twentieth century, and to post-colonial Trinidad. Here, in a rural backwater, on an uncertain day in an unnamed year, a baby is born to a life of struggle and anxiety. Trinidad, a Caribbean island off the coast of Venezuela, was colonized first by the Spanish, then the French and then the British. It was a place which oil eventually made rich but where much of the population had always lived in poverty; where from the late nineteenth century Indian indentured labourers worked on the sugar-cane plantations, replacing the African slaves who were finally, in 1834, granted emancipation throughout the British Empire. In truth, these new arrivals, transported in terrible conditions, lived lives which were not so far from slavery.

Two such labourers were V. S. Naipaul’s maternal grandparents: high-caste Hindus. His father, Seepersad, whose own Indian origins are uncertain, and who began his working life as a sign-painter, married one of their daughters in 1929. In so doing, he entered a large, commanding, matriarchal family who supported him but often made his life unendurable.

A House for Mr Biswas is a portrait

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inA House for Mr Biswas was my lockdown book. As cases of Covid climbed, and the loveliest spring was filled with fear, I took myself back to the first half of the twentieth century, and to post-colonial Trinidad. Here, in a rural backwater, on an uncertain day in an unnamed year, a baby is born to a life of struggle and anxiety. Trinidad, a Caribbean island off the coast of Venezuela, was colonized first by the Spanish, then the French and then the British. It was a place which oil eventually made rich but where much of the population had always lived in poverty; where from the late nineteenth century Indian indentured labourers worked on the sugar-cane plantations, replacing the African slaves who were finally, in 1834, granted emancipation throughout the British Empire. In truth, these new arrivals, transported in terrible conditions, lived lives which were not so far from slavery. Two such labourers were V. S. Naipaul’s maternal grandparents: high-caste Hindus. His father, Seepersad, whose own Indian origins are uncertain, and who began his working life as a sign-painter, married one of their daughters in 1929. In so doing, he entered a large, commanding, matriarchal family who supported him but often made his life unendurable. A House for Mr Biswas is a portrait of this clever, difficult, fragile man, struggling for autonomy in impossible circumstances. Published by André Deutsch in 1961, the book began for Naipaul with the poignant recollection of the handful of household goods and furniture – a meat safe, a chair, a bookcase and hat rack – which accompanied his parents with every move they made. Gradually, these simple things opened up a great seam of memory, transformed, through the workings of imagination, into art.He had thought deeply about this house, and knew exactly what he wanted. He wanted, in the first place, a real house, made with real materials. He didn’t want mud for walls, earth for floor, tree branches for rafters and grass for roof. He wanted wooden walls, all tongue-and-groove. He wanted a galvanised roof and a wooden ceiling . . . The kitchen would be a shed in the yard; a neat shed, connected to the house by a covered way. And his house would be painted. The roof would be red, the outside walls ochre and the windows white.

‘You see, Ma. I have no father to look after me and people can treat me how they want . . . I am going to get a job on my own. And I am going to get my own house, too. I am finished with this.’ He waved his aching arm about the mud walls and the low, sooty thatch.In a different time, and in a different diction, the words could be spoken by David Copperfield. Seepersad, a fine writer himself who became a journalist, was entranced by Dickens, and the crowded, epic sweep of this book, with a vulnerable, tragi-comic hero whom we grow to love, can only be described as Dickensian. As the African- American writer Teju Cole expresses it in his magnificent introduction to my Picador Classic edition, A House for Mr Biswas ‘brings to startling fruition in twentieth-century Trinidad the promise of the nineteenth-century European novel’. Naipaul’s work is a mighty creation, revealing an entire world through the experience of a kind of Everyman – someone who yearns for the one thing everyone needs: a home. It takes five moves and several jobs, over decades, before he can close his own, ill-fitting front door. The Monday morning after his outburst to his mother, Mr Biswas sets forth. He is perhaps 16, and only as a baby has he known any kind of tenderness. He has been educated in colonial style with the recital of tables, an introduction to oases, igloos and the Great War, via ‘the Lord’s Prayer in Hindi from the King George V Hindi Reader’. His only gift has been in lettering, for which he has great feeling. ‘How did one look for a job? He supposed that one looked. He walked up and down the Main Road, looking.’ The road is hot, crowded, noisy. He passes tailors, undertakers, gloomy dry-goods shops, vegetable stalls whose holders stare at him. He can imagine himself in none of these places, and returns to tell his mother, ‘I am not going to take any job at all. I am going to kill myself.’ It is an old schoolfriend, working as a sign-painter, who rescues him, taking him on as his assistant. Through this job Biswas meets Shama Tulsi, a silent, pretty young girl working in the cavernous family store, with whom he stumbles into marriage. Here is the first of his moves: from his mother’s dark little hut to Hanuman House, the Tulsi family home. ‘[The Tulsis] had some reputation among Hindus as a pious, landowning family.’ They certainly have money, though no one is quite certain where first it came from. Their house, ‘an alien white fortress’, is crowned with a statue of the Hindu monkey-god Hanuman, affording an enraged or irritable Mr Biswas many opportunities to call it a monkey-house. The family is enormous: countless married daughters and their offspring, and two ambitious sons who are treated like gods. An undifferentiated mass of malnourished children peep out from doorways, scamper laughing into the yard, sleep in rows on the upper floor, weep when they are beaten. They are beaten (sometimes flogged) very often, something which is as much a part of daily life as the women’s endless cooking, the demanding return of their husbands from the fields. Every man, noisily eating rice and vegetables from brass plates, is assiduously attended to by his wife. Mr Biswas dislikes eating off brass plates and dislikes the food. He is often to be found in retreat, lying on his bed upstairs in vest and underpants (made from flour sacks, the lettering still visible, to general hilarity) reading the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. It is not long before he becomes the buffoon intruder, and after a fight is evicted, though Mrs Tulsi sets him up in a scrap of a shop, ‘a short, narrow room with a rusty galvanised iron roof ’. By now Shama is pregnant. Her frequent return to Hanuman House after their first daughter is born, and subsequent return to Mr Biswas, sets the pattern for their marriage: immensely difficult but, in spite of everything, enduring. Shama emerges as capable and strong, sometimes even kind, and she knows him through and through. Their exchanges are often tough, and very funny.

‘And how the old queen?’ That was Mrs Tulsi. ‘The old hen? The old cow?’ ‘Well, nobody did ask you to get married into this family, you know.’ ‘Family? Family? This blasted fowlrun you calling family?’Six years in the oppressive little shop, where Mr Biswas commissions a house which is never finished, are followed by a move of the entire family to Green Vale, close to the Tulsi plantation. Now working as a sub-overseer, Biswas is housed in a barrack room whose every wall is lined with newspapers and cut-off headlines. AMAZING SCENES WERE WITNESSES YESTERDAY WHEN. These words sink into him for ever. In another family move, this time to the hills, he builds another house, which is destroyed by fire. Despair engulfs him. By now, three more children have arrived, the second a boy, Anand. Like Naipaul, he will one day win a scholarship to Oxford. His developing patience with his father’s often outrageously difficult temperament, when he himself is suffering, is one of the most moving threads of the novel. Eventually, Biswas storms from the Tulsi household. Alone and furious, he leaves at last the huts, the dusty roads, the acres of sugar- cane and the buffalo-carts of village life, discovering ‘the shops and cafés and buses, cars, trams and bicycles, horns and bells and shouts’ of the streets of Port of Spain, the island’s little capital. Here, from the open windows of the newspaper offices, he hears machinery rattling and inhales the warm smell of oil, ink and paper. And here the sign-writing job he took almost by accident proves to be the most useful training he could have had. As a sign-writer he is taken on by the Sentinel – Naipaul’s version of the Trinidad Guardian, where his father worked – and when he submits a story along the line of AMAZING SCENES he is given a chance as a journalist. He has entered at last the dreamed-of world of writing. Books, since his youth, have sustained and comforted him. He sends for his family. I will leave the reader to discover, years later, the gimcrack place he can finally call his own, and the understated tenderness of the novel’s ending. Naipaul described his father’s reading to him when he was a little boy as offering ‘the richest imaginative experience of my childhood’. As an adult, he often distanced himself from Trinidad. Yet he once wrote that ‘Half of a writer’s work . . . is the discovery of his subject.’ Following the instruction of his yearning, frustrated father, to ‘write about what you know’, he made his discovery. And knowing everything about the place where he grew up – its hot, crowded city streets; ‘the flat acres of sugar-cane and the muddy ricelands’; the shouting and stoicism of Hindu family life – interweaving it all with the universals of human suffering and endurance, he created in A House for Mr Biswas what Teju Cole has called one of the imperishable novels of the twentieth century.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 70 © Sue Gee 2021

About the contributor

Sue Gee was conceived in India and born in Dorking. Her novel Coming Home (2013) tries to come to terms with this.