In the early days of Slightly Foxed, in our very first issue in fact, I wrote about a book that had once come my way in the course of my work as a publisher’s editor – a book that had entranced me. Suzanne St Albans’ memoir Mango and Mimosa told the story of her eccentric upbringing in the 1920s and ’30s, when her family moved restlessly between the home her two lovable but ill-assorted parents had created out of the ruins of an old farmhouse near Vence, at the foot of the Alpes-Maritimes, and Assam Java, the plantation her father had inherited in Malaya, at Selangor.

I wrote this piece long before our Slightly Foxed Editions were even thought of, and as with a number of other memoirs we featured in our early issues, which have now slipped out of print, we’re delighted to be able to reissue this lovable book as the latest SFE. So, for those readers who haven’t already made its acquaintance, this is a brief introduction, and a reminder for those who have.

Reading it again has made me think about what makes a successful memoir. Primarily, I suppose, it is the writer’s ability to speak to the reader with an entirely individual voice, and that is certainly true of Suzanne St Albans (or Suzanne Fesq, as she was until she married the 13th Duke of St Albans in 1947 – an event too far in the future to feature here). From the opening page one has the sense of being with someone funny and spontaneous, with tremendous zest and an original take on life, and an acute and affectionate eye for the oddities of human – and animal – behaviour.

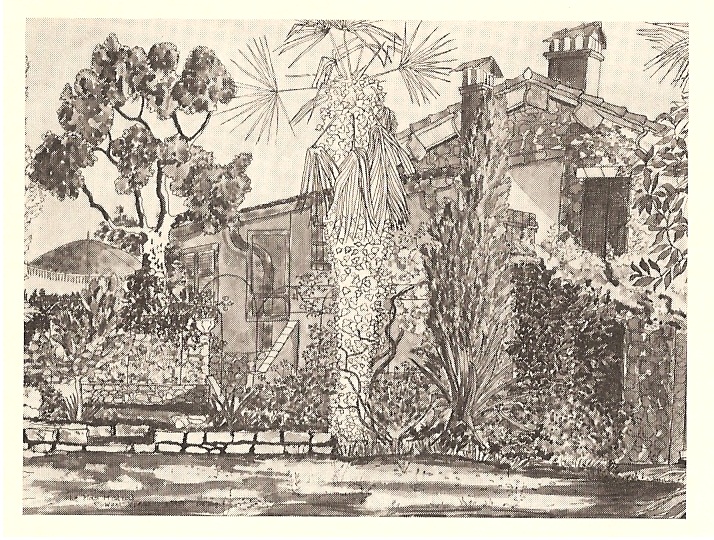

She also has a wonderful ability to evoke the feeling of those places where she spent her childhood – the dreamy atmosphere of the old Provençal farmhouse, which her parents christened Mas Mistral – ‘after the poet, not the wind’ – along the front of which ‘ran a balcony festooned with bignonia, wisteria and moonflowers climbing up from the terrace below, so that for six month

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIn the early days of Slightly Foxed, in our very first issue in fact, I wrote about a book that had once come my way in the course of my work as a publisher’s editor – a book that had entranced me. Suzanne St Albans’ memoir Mango and Mimosa told the story of her eccentric upbringing in the 1920s and ’30s, when her family moved restlessly between the home her two lovable but ill-assorted parents had created out of the ruins of an old farmhouse near Vence, at the foot of the Alpes-Maritimes, and Assam Java, the plantation her father had inherited in Malaya, at Selangor.

I wrote this piece long before our Slightly Foxed Editions were even thought of, and as with a number of other memoirs we featured in our early issues, which have now slipped out of print, we’re delighted to be able to reissue this lovable book as the latest SFE. So, for those readers who haven’t already made its acquaintance, this is a brief introduction, and a reminder for those who have. Reading it again has made me think about what makes a successful memoir. Primarily, I suppose, it is the writer’s ability to speak to the reader with an entirely individual voice, and that is certainly true of Suzanne St Albans (or Suzanne Fesq, as she was until she married the 13th Duke of St Albans in 1947 – an event too far in the future to feature here). From the opening page one has the sense of being with someone funny and spontaneous, with tremendous zest and an original take on life, and an acute and affectionate eye for the oddities of human – and animal – behaviour. She also has a wonderful ability to evoke the feeling of those places where she spent her childhood – the dreamy atmosphere of the old Provençal farmhouse, which her parents christened Mas Mistral – ‘after the poet, not the wind’ – along the front of which ‘ran a balcony festooned with bignonia, wisteria and moonflowers climbing up from the terrace below, so that for six months of the year at least the whole front was covered with thick clusters of flowers’. And the steamy jungle heat of Assam Java, where electric storms thundered around the sky, and where the children were never allowed to run on the upper floor of the house lest it collapse, because the timbers were riddled with termites: ‘We slept under the rafters and the palm leaf roof . . . Rats and squirrels peered down at us, snakes and insects of every kind crawled in and out of the palm thatch, and frequently plumped to the floor with a thud and a squelch.’ In fact living creatures of all kinds featured large in the Fesq household, for Marie, their father’s severe Swiss nanny who had been pressed into service again when he himself produced children, was a keen naturalist. The nursery shelves were filled with bottles of pickled specimens, and in the courtyard at Assam Java lived a menagerie of assorted creatures, some rescued, some adopted, with broken legs or wings expertly mended by Marie. Baby birds fallen from the nest were fed mashed-up worms with stamp-collecting tweezers, the little household monkey curled up on any convenient lap, a rescued stork liked to join the family at badminton, and Titi the pet hen, assisted by a small ladder, laid her eggs in the nursery wardrobe among the children’s clothes. Marie, morbid and disciplinarian though she might have been, was the fixed point in the children’s turning world, and they adored her. She in turn adored their father and disliked (and no doubt envied) their mother – he a frail and intellectual recluse, who found family life a dreadful strain and hid in the cellar when visitors came, she a sociable, restless, impulsive being, who Marie felt was frivolous and a bad influence generally. Madame Fesq’s attitude to education was certainly casual to say the least, and Suzanne was pulled in and out of establishments ranging from the local village school in Provence to a grim convent in Paris and a girls’ school in Littlehampton – none of which lasted long. Another fixed point for Suzanne, her brother and two sisters were the idyllic summers the family spent on the long white beaches of the Atlantic coast, where they met up with their mother’s friends the Darlanges. From the beginning the Darlanges’ handsome son Jacques was Suzanne’s bosom pal. As they both grew up, he clearly began to want a different, more adult relationship, but, tomboy that she still was, she wasn’t ready, and shied away. It’s a wonderful account of the confusions, embarrassments and misunderstandings of first love. Then in the late summer of 1939 war was declared. The German Occupation scattered the two families to the winds, with the Fesqs – who for complicated reasons had British passports – fleeing to England and forced to abandon Marie in France. Meantime their father was marooned in South-east Asia, where he spent most of the war in a prison camp. It was the end of Suzanne’s childhood, and the point at which this story ends. I met the late Duchess briefly only once, when she was in her eighties, but I learned from her obituaries that during the war she had worked in Psychological Warfare as a news writer in North Africa and Italy, and then in 1945 in Austria where she met and fell in love with the amusing and dashing Colonel Charles Beauclerk. When he finally inherited the dukedom (at birth he was only ninth in line), it came with a string of titles, including that of Grand Falconer of England, but very little else. In an effort to recoup the family fortunes he embarked on an ill-advised business career which foundered spectacularly and ignominiously in 1973, and they lost virtually everything. So he and the Duchess retired to Mas Mistral where, in her usual spirited way, she took up her pen and produced this memoir – partly, presumably, in the hope of making some money, and partly perhaps to recapture some of that happy lost childhood world – as well, apparently, as ‘five other non-fiction books’ which I have been unable to trace. Not bad for someone whose first language was French, and who never seems to have gone to school for more than a year at a time – though perhaps that was her saving grace, for she retained a youthful enthusiasm and freshness which permeate this funny and magical memoir. She was certainly quite a gal.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 33 © Hazel Wood 2012

About the contributor

Hazel Wood grew up with a menagerie of creatures, but is now petless following the sudden tragic death of Dan the cat.