For me it all started the night Max wore his wolf suit and made mischief of one kind or another. But then again, that’s how it started for most of us who’ve read Maurice Sendak. Max is the hero of Sendak’s best-known work Where the Wild Things Are. First published in 1963, it has sold over 17 million copies worldwide, and has entertained, delighted and intrigued who knows how many millions of children and adults.

I love it because it is wonderful, beautiful and strange. When I asked my 10-year-old daughter why she liked it she said, ‘because the pictures are funny and his room turns into jungle and his supper’s waiting for him when he gets back’. In many ways this is a far better summary than anything I could attempt. Still, I’ll have a go. The plot is simple. Max, a boy in a white wolf suit, is misbehaving one evening. He bangs a nail in a wall to support a bedclothes tent. He suspends a forlorn teddy by string from a coat-hanger. And wielding a fork he leaps down the stairs chasing a small white dog.

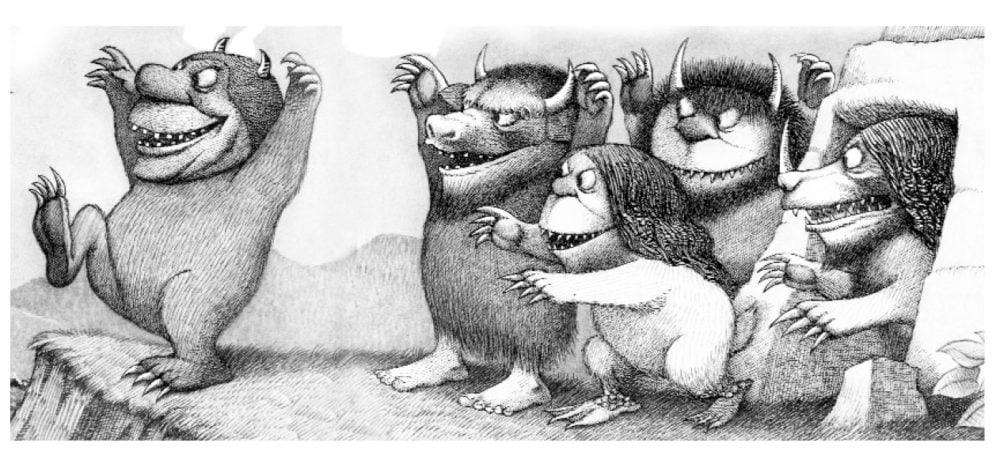

His mother calls Max a ‘wild thing’ and when he threatens to eat her up he’s sent to bed without any supper. Banished to his room he discovers it magically transformed into a forest. He finds a boat, sails an ocean, and ends up on an island of terrible monsters that he tames by staring into their eyes. The monsters declare Max their king and they dance and cavort together across three wordless double-page spreads. But Max gets bored and sails home, back to his bedroom, where his supper is waiting for him.

Sendak tells the whole story in ten sentences. In all there are only 338 words. But there are also eighteen glorious pictures which take you from the small world of childhood boredom that we can all remember to the unrestrained empire of a child’s imagination. The colours used are subtle and understated.

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inFor me it all started the night Max wore his wolf suit and made mischief of one kind or another. But then again, that’s how it started for most of us who’ve read Maurice Sendak. Max is the hero of Sendak’s best-known work Where the Wild Things Are. First published in 1963, it has sold over 17 million copies worldwide, and has entertained, delighted and intrigued who knows how many millions of children and adults.

I love it because it is wonderful, beautiful and strange. When I asked my 10-year-old daughter why she liked it she said, ‘because the pictures are funny and his room turns into jungle and his supper’s waiting for him when he gets back’. In many ways this is a far better summary than anything I could attempt. Still, I’ll have a go. The plot is simple. Max, a boy in a white wolf suit, is misbehaving one evening. He bangs a nail in a wall to support a bedclothes tent. He suspends a forlorn teddy by string from a coat-hanger. And wielding a fork he leaps down the stairs chasing a small white dog. His mother calls Max a ‘wild thing’ and when he threatens to eat her up he’s sent to bed without any supper. Banished to his room he discovers it magically transformed into a forest. He finds a boat, sails an ocean, and ends up on an island of terrible monsters that he tames by staring into their eyes. The monsters declare Max their king and they dance and cavort together across three wordless double-page spreads. But Max gets bored and sails home, back to his bedroom, where his supper is waiting for him. Sendak tells the whole story in ten sentences. In all there are only 338 words. But there are also eighteen glorious pictures which take you from the small world of childhood boredom that we can all remember to the unrestrained empire of a child’s imagination. The colours used are subtle and understated. And the drawing is meticulous. But the monsters are astonishing. They somehow manage the impossible feat of being both scary and funny, strange and familiar. In The Art of Maurice Sendak (1980) Selma G. Lanes reveals that when the book first appeared it caused controversy. Publishers Weekly advised: ‘The plan and technique of illustrations are superb, but they may well prove frightening, accompanied as they are by a pointless and confusing story.’ Parents sent in letters of complaint. And one librarian went so far as to write, ‘It is not a book to be left where a sensitive child may come upon it at twilight.’ Looking back at these comments almost fifty years later it is clear that they are ridiculous. But the odd thing is that they are also true. Where the Wild Things Are is pointless, and confusing and frightening. And if it were to land on the desk of a children’s publisher today it would probably fall foul of that most insidious of questions: ‘Yes, it is a very intriguing book, Mr Sendak, but what age of child do you think it’s aimed at?’ Fortunately for Sendak he had an editor in Ursula Nordstrom at Harper & Brothers who, though at first unsure about the book, soon came round. She wrote to the author, ‘It is adults we have to contend with – most children under the age of ten will react creatively to the best work of a truly creative person. But too often adults sift their reactions to creative picture books through their own adult experiences. And, as an editor who stands between the creative artist and the creative child, I am constantly terrified that I will react as a dull adult.’ Maurice Sendak was born on 10 June 1928 in Brooklyn, New York. His parents had arrived as immigrants before the First World War. Both came from small Jewish shtetls outside Warsaw. As a result he grew up, like so many second-generation immigrants, deeply influenced by a culture clash. On the one hand were the traditions of the old country and village life, on the other the booming New World mayhem of 1930s America where anything might be possible. Sendak himself has crystallized this conflict by saying that when he was small the two dominant figures in his life were his maternal grandfather – a Talmudic scholar who never left Poland and whom he never met – and Mickey Mouse. Sendak was a sickly child. To him ‘life seemed one long series of illnesses’. He contracted measles when he was 2. Next came pneumonia. Then, when he was 4, scarlet fever struck. As a result he was over-protected and spent much of his time watching life through a window. Unsurprisingly he developed a talent for observation. He also read a lot. Books seemed alive to him. When he was finally allowed out to play with the kids in his neighbourhood, though he might not have been able to hold his own in the rough-and-tumble of street life, he did discover that he could hold the attention of his peers by retelling the stories of movies that he had seen. Given all this, the roots of his later life as a writer and artist are clear. But the roots of a plant rarely tell you what the plant itself is going to be like. Take his talent for observation, for example. How does that manifest itself in a book like Where the Wild Things Are? The answer, somewhat surprisingly, is that Sendak had directly observed the Wild Things as a child in the form of his Jewish relatives, who would make anxiety-inducing visits to the family home every Sunday and poke and prod and pinch cheeks and coo over him, and who seemed to eat up all the food. In many ways this insight into the origins of the Wild Things is an excellent summary of one aspect of Sendak’s extraordinary talent. He takes the everyday, the mundane, the unremarkable and reimagines it. And while we may never know where exactly something in one of his books has come from, the fact that it has come from somewhere gives the story a resonance that strikes a chord within us. Mind you, the book of his that I love the most has, for me, a far simpler appeal. It’s mad. It is called In the Night Kitchen. A small boy called Mickey can’t get to sleep because there’s a racket going on downstairs. He gets up and shouts ‘Quiet down there!’ And ends up falling into the night kitchen where a trio of bakers are baking the morning cake. Unfortunately the bakers run out of milk. But Mickey saves the day (or perhaps the night?) by building a plane out of dough and flying up to a giant milk bottle and pouring milk down to the waiting bakers. The night kitchen itself has as a backdrop a New York skyline made up of food boxes, cartons and bottles. But my favourite part of the book is the bakers themselves. For no discernible reason they all look like Oliver Hardy. In the Night Kitchen appeared seven years after Where the Wild Things Are and never achieved anything like the same success. But it did succeed in being banned from many libraries. This was mainly because as Mickey falls from his bed he loses his clothes. The book also invited all manner of psychological interpretations. Whether such analyses are valid is debatable. But what is clear is that the rich hinterland of Sendak’s work means there is a lot of stuff to delve into, if delving into stuff is important to you. Should you be interested, here is a breakdown of some of the ingredients of the book. The structure of the story – a small boy falling out of bed into an incredible adventure – clearly owes much to the newspaper comic strip ‘Little Nemo in Slumberland’, first created in 1905 by the genius Winsor McCay. There is a nod towards Mickey Mouse in the hero’s name. The concept of a night kitchen comes from an advert remembered from childhood for the Sunshine Bakers who proudly proclaimed ‘We Bake While You Sleep!’ And the skyline made of food containers may well be a reference to trips from Brooklyn into the magical land of Manhattan to see movies at the Radio City Music Hall and to eat dinner beforehand in a restaurant. The autobiographical nature of the book is more explicitly revealed in small details in the pictures. The names of friends and colleagues are used on the food packages. Sendak’s beloved dog Jennie is memorialized on a sack of flour. Two addresses that were once home are featured. And a coconut carton is inscribed with the author’s date of birth. Late on in the book there is even a building that bears the legend ‘Q. E. Gateshead’. This is a reference to a 1967 trip to England where, during a BBC interview, Sendak had a major coronary attack that was originally diagnosed as severe indigestion. Luckily for him (and indeed for all of us) Judy Taylor, his English editor who was accompanying him, insisted that more was amiss, and his life may well have been saved by the treatment he received at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Gateshead. But what of the bakers, why do they look like Oliver Hardy? In the very earliest sketches for the book one of the bakers is a cat, one a dog and one a pig. But then a chance encounter with a TV showing of an old Laurel and Hardy movie occurred. Still, in many ways all this information and explanation is irrelevant. I fell for In the Night Kitchen knowing none of it. I responded to the pictures and the words. And though I first picked up the book as an adult, its magic is so great that I read it as a child would. If an author can do that to you, then he is truly blessed. All of which brings us to Outside Over There. In Sendak’s mind this third book completes the trilogy. But it is a strange trilogy. None of the books feature the same characters, setting or narrative. If there is a link between them it may lie in the fact that they all attempt to deal with the nature of childhood, or certain aspects of it. Outside Over There is one of the most disturbing books I have ever read. If Where the Wild Things Are is a fantasy, and In the Night Kitchen a dream, Outside Over There is a nightmare. It is the story of a baby girl whose father goes away to sea, whose mother lapses into depression and who, while being looked after by her sister, is kidnapped by grey-robed faceless goblins intent on marrying her. Thankfully the sister climbs backwards out of her window and rescues the baby. But not before discovering that the goblins are themselves babies whom she defeats by playing a tune on her French horn that causes them to cavort uncontrollably until they dissolve into a ‘dancing stream’. In my opinion, it is not a book to be left where a sensitive adult may come upon it at twilight. While In the Night Kitchen spoke directly, and joyously, to the child within me, Outside Over There seems to head straight for my adult self, homing in on long-submerged fears and hauling them to the surface. It seems to me to be a book about loss, separation and abandonment. And though the ending is happy, what has preceded it is so powerful that it is not the resolution that lingers in the mind. As such, I think the book fails. But, perversely, it is its very failure that confirms just how good, and important, a writer and artist Sendak is. The parallel that comes to my mind is, strangely, from the 1970 World Cup in Mexico. Pelé, the greatest footballer who ever lived, was on the halfway line when the opposing goalkeeper took a goal kick. The ball landed inches in front of Pelé. Without breaking stride the Brazilian smacked the ball straight towards the goal. The shocked goalkeeper back-pedalled furiously and turned to see the shot miss the goal by inches. The fact that Pelé missed was incidental. What confirmed his brilliance was that he had the audacity to try the shot in the first place. And that, in a sense, is what I feel about Sendak. First he redefined what was possible. And then he attempted the impossible. But, if he failed, as Beckett might have put it, he failed better. One last train of thought occurs to me. Sendak spent much of his early childhood observing life through a window, and his first fulltime job was working for a company that arranged window displays for Manhattan stores. So, for him, a window was not only something you look out of to see what’s going on outside, but also something you look in through to see what’s going on inside. And a window display, if it is really to catch the eye, can never feature everything that’s available inside the shop. You just need to choose the things that will interest, intrigue and entice. But even as you look at it you know that if you venture through the door, you’ll find a whole lot more. And maybe that’s the true genius of Sendak’s books. They are windows. Windows you can look out of to see a narrative unfold before your eyes. And, should you wish, windows you can look into to catch glimpses of the most compelling of interiors.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 20 © Rohan Candappa 2008

About the contributor

Rohan Candappa is an author of humorous books. But due to laughable sales of the last one he’s gone back to advertising. Any serious job offer considered.