Many writers reported finding it hard to focus during the Covid lockdowns, beset as they were by anxiety and feelings of futility. Eighty years ago, a writer produced remarkable novels under a far more onerous lockdown during the Second World War. Where we hid from an invisible virus, he was under German occupation, and then Allied bombardment.

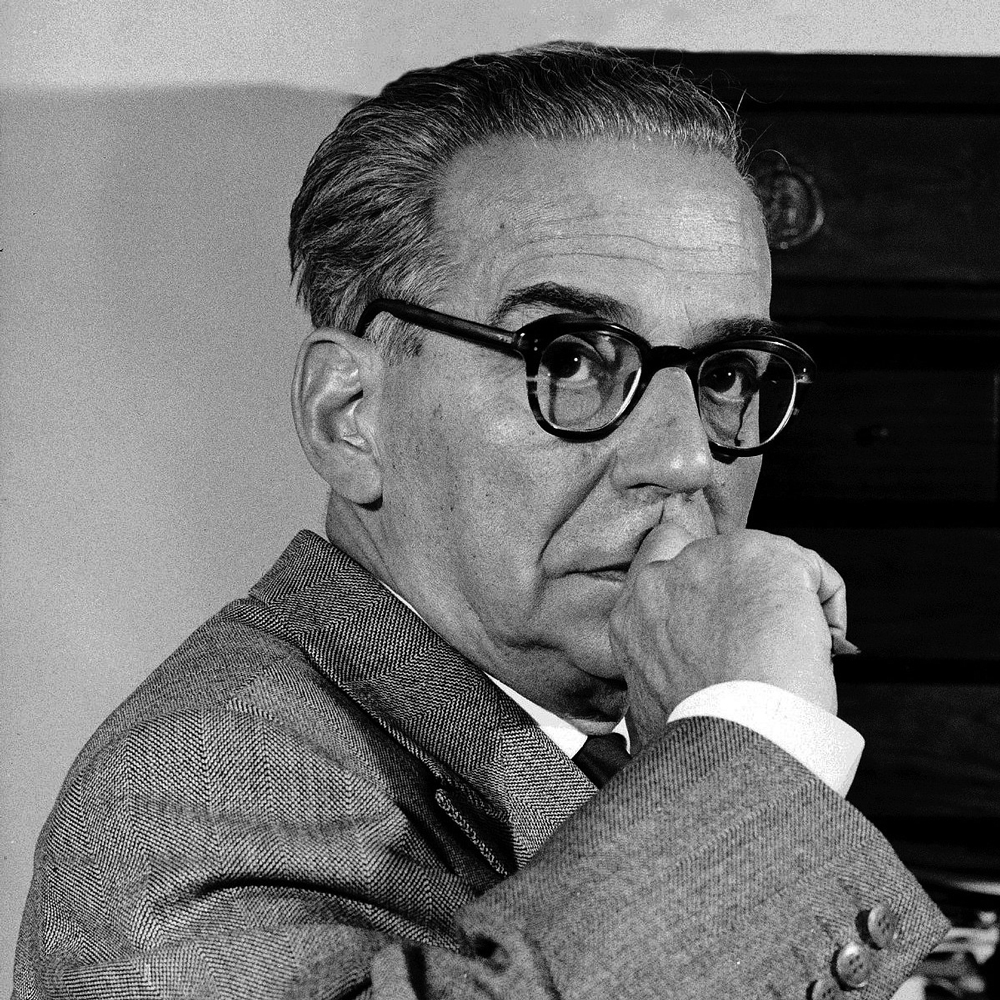

Born in 1892, Ivo Andrić was a Yugoslav writer, and also a diplomat whose career reached its peak with unfortunate timing in 1939, when he was appointed as Yugoslavia’s Minister Plenipotentiary and Envoy Extraordinary to Berlin. In September of that year German forces invaded Poland, and Britain and France declared war. Thereafter, Yugoslavia attempted a tortuous neutrality, though under increasing pressure from Germany to side with the Axis. Seeing where this pressure would lead, Andrić submitted his resignation to the authorities in Belgrade: ‘I request that I be relieved of these duties, and recalled from my current post as soon as possible.’

His request was denied. Eventually, on 25 March 1941, the Yugoslav government followed Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria into the embrace of the Axis. The Yugoslav military, however, proudly refused to accept this acquiescence: two days later army officers staged a coup d’état and asserted their country’s independence. Hitler was infuriated that this small Balkan country had dared to defy him. ‘The hammer must fall on Yugoslavia without mercy,’ he decreed. The country was attacked from all sides, on land and from the air. This Blitzkrieg lasted just ten days: the Royal Yugoslav Army capitulated on 17 April.

Ivo Andrić and the rest of the Yugoslav Legation staff in Berlin had been put on a train out of Germany. Most took refuge in neutral Switzerland, but Andrić continued his journey to Belgrade. An old friend, the lawyer Brana Milenković, met Ivo at the railway station and took him back to the house in the centre of Belgrade where he lived with his

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inMany writers reported finding it hard to focus during the Covid lockdowns, beset as they were by anxiety and feelings of futility. Eighty years ago, a writer produced remarkable novels under a far more onerous lockdown during the Second World War. Where we hid from an invisible virus, he was under German occupation, and then Allied bombardment.

Born in 1892, Ivo Andrić was a Yugoslav writer, and also a diplomat whose career reached its peak with unfortunate timing in 1939, when he was appointed as Yugoslavia’s Minister Plenipotentiary and Envoy Extraordinary to Berlin. In September of that year German forces invaded Poland, and Britain and France declared war. Thereafter, Yugoslavia attempted a tortuous neutrality, though under increasing pressure from Germany to side with the Axis. Seeing where this pressure would lead, Andrić submitted his resignation to the authorities in Belgrade: ‘I request that I be relieved of these duties, and recalled from my current post as soon as possible.’ His request was denied. Eventually, on 25 March 1941, the Yugoslav government followed Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria into the embrace of the Axis. The Yugoslav military, however, proudly refused to accept this acquiescence: two days later army officers staged a coup d’état and asserted their country’s independence. Hitler was infuriated that this small Balkan country had dared to defy him. ‘The hammer must fall on Yugoslavia without mercy,’ he decreed. The country was attacked from all sides, on land and from the air. This Blitzkrieg lasted just ten days: the Royal Yugoslav Army capitulated on 17 April. Ivo Andrić and the rest of the Yugoslav Legation staff in Berlin had been put on a train out of Germany. Most took refuge in neutral Switzerland, but Andrić continued his journey to Belgrade. An old friend, the lawyer Brana Milenković, met Ivo at the railway station and took him back to the house in the centre of Belgrade where he lived with his mother and sister, who made two rooms available to their guest. As well as being occupied by the Germans, Yugoslavia was then consumed by a ferocious civil war between the Fascist Ustasha in Croatia, the Royalist Serb Chetniks and Tito’s Communist Partisans. Belgrade, half ruined by the German bombardment, was now flooded with refugees. From his rooms, Andrić could see floating in the Sava river the corpses of Serbs killed by Ustasha and ‘posted’ to Belgrade. The bodies sometimes clogged the river under the new bridge that the Germans were building. Their engineers used hand grenades to clear the human blockage. Reprisals for resistance to the occupiers were brutal: for any German soldier wounded, fifty Yugoslav civilians were rounded up and executed; a German soldier killed meant a hundred civilians executed. In addition, the Quisling government ordered prominent public figures to sign a proclamation that condemned all resistance. Many did sign, regardless of their patriotic feelings or political convictions. When a courier brought the text of the proclamation to Andrić for his signature, he refused, saying: ‘Tell them that he wasn’t at home.’ The courier, however, recognized the writer. ‘But Mr Andrić,’ he insisted, ‘it is you!’ ‘Well, if you are so smart,’ Andrić replied, ‘you can tell them I told you that I wasn’t at home,’ and closed the door. Now aged 48, Andrić retired from the Diplomatic Service but refused to accept a pension, instead living simply on his savings. In the ruins of Belgrade, he busied himself running errands for those who needed help distributing what food and medicine could be found, and keeping spirits up. Each evening he shared the Milenkovićs’ meagre dinner. He also started writing. Bosnian Chronicle (1945) had first been conceived almost twenty years earlier, when Andrić was a junior attaché in Yugoslavia’s consulate in Paris. He made no friends there and found himself isolated and lonely. ‘Apart from official contacts,’ he wrote in a letter home, ‘I have no company whatsoever.’ Instead, through 1927 and 1928 he spent all his free time in the Paris archives, poring over the three volumes of reports sent to the French Foreign Ministry at the beginning of the nineteenth century by Pierre David, their consul in Bosnia, and making notes. Now, in German-occupied Belgrade in 1941, armed with these notes, Andrić set to work on his novel. Napoleon’s military successes had established the ‘Illyrian Provinces’ in Dalmatia. The French then requested from the Ottoman Empire a consulate in Travnik, administrative capital of the Ottoman province of Bosnia, to establish safe and reliable trade routes through the Balkans. Bosnia was ruled by a Vizier, or governor, an Ottoman who found himself miserably far from Istanbul, amongst people who resented him as the representative of their oppressive Turkish colonizer. Jean Daville, Andrić’s French consul, is the principal character in Bosnian Chronicle, which follows him from his arrival in Travnik in 1807 to his departure – and the closure of the consulates – seven years later. Though it is apparent to the reader that the Frenchman carries out his diplomatic obligations with good grace, he is psychologically ill-suited to the role, being privately indecisive and continually tortured by the fear of having made the wrong move or misread someone else’s. He, the Vizier and the Austrian consul Josef von Mitterer are engaged in a never-ending game of saying – through interpreters – one thing while meaning another, each trying desperately to decipher the truth behind his counterpart’s obfuscations, and to further his own Empire’s interests. A major theme of the novel is the impossibility of communication, between east and west no less than between individuals, which is nowhere clearer than when the Vizier invites the consuls to the palace to celebrate his latest skirmish against Serb rebels. War trophies are scattered on the rug for the foreigners to admire: amid the captured weapons, Daville is horrified to realize that there are also piles of noses and ears, presented triumphantly by the Vizier, who is oblivious to the Frenchman’s horror – which he in turn, for the sake of diplomacy, must conceal. In this he is helped by von Mitterer, for the Austrian is a military man, more easily able to control his emotions. The two foreigners are bound together. ‘Their unhappy fate and the difficulties it brought drove them towards each other,’ Andrić writes. ‘And if ever there existed in the world two men who could have understood, sympathized with and even helped one another, it was these two consuls who spent all their energy, their days and often their nights putting obstacles in each other’s way and making each other’s life as troublesome as possible.’ Momentous events like Napoleon’s doomed assault on Moscow or the War of the Sixth Coalition take place far away. The Vizier and the consuls are puppets on a string, with fixed roles to play but powerless to influence events. They and their respective families and entourages are exiles, in Travnik temporarily, while the minor characters who people the novel, the indigenous Bosnian Muslims, Catholics, Serbian Orthodox Christians, Jews and Gypsies, watch from the sidelines. Andrić’s style is discursive. He builds a galaxy of characters, the stars and their satellites spinning around each other, their stories told in anecdotal chapters: one is devoted to the three town drunks, another to a Catholic monk dedicated to healing with herbal medicines, a third to the impossible love affair between von Mitterer’s wife and Daville’s young assistant. In one chapter we meet the chief member of the Vizier’s household. His treasurer, Baki, had been keeping the Vizier’s accounts for years now, conscientiously and accurately, saving every last grosch with the tenacity of an inveterate miser and defending it from everyone, including the Vizier himself . . . He ate little and drank only water, and every mouthful he saved was sweeter than any he ate. Andrić gives us the world of Travnik in all its variety and depth, and he uses the ebb and flow of politics almost as a pretext to delve into the minds of those entrapped in the town. Bosnian Chronicle is at once satirical and psychoanalytical, and in both its structure and its humour, it bears striking similarities to Catch-22. Indeed one could hardly believe Joseph Heller hadn’t read it if it wasn’t for the fact that the first translation into English didn’t come out until the same year as Catch-22 was published. The novel opens with local Muslim beys sullenly anticipating the imminent arrival of the consuls, and it ends with them enjoying the foreigners’ departure.*

Conditions in Belgrade, meanwhile, deteriorated further in 1942. Coal was rarely available, food increasingly scarce, people scavenged for scraps. Where we under lockdown suffered brief shortages of toilet paper and pasta, in German-occupied Europe people ate boiled rat-meat and pine-needle stew. That winter, thousands starved in Belgrade. Andrić’s long-time confidante, Vera Stojić, visited him regularly and typed up the pages of the manuscript of Bosnian Chronicle as he produced them. Then the Serbian Literary Association asked Andrić for a submission. The letter of invitation displayed the signature of a poet and translator of Shakespeare with well-known German sympathies and some influence with the occupying authorities. Andrić replied. Instead of offering vague excuses or false promises, he wrote that he did not intend to publish anything with his country under occupation, ‘while the people are suffering and dying’. He then packed a small suitcase and awaited the arrival of the Gestapo. They never came. After the war, the secretary who worked for the Association, and who knew Andrić’s earlier work, revealed that she had opened and read the letter, and had quickly buried it in the archives before anyone else had an opportunity to see it. No sooner had he finished Bosnian Chronicle than Andrić promptly started work on what would become another masterpiece, the second of his three great novels, and his most famous book, The Bridge on the Drina. In 1944, from April to September, it was the Allies’ turn to pulverize Belgrade. Andrić would later tell a friend, Zuko Dzumhur, how frightened he was by the sudden scream of the sirens that warned of the first raid. He ran out of the house and joined the column of frantic people fleeing the city. As he was swept along, he looked around him and realized that all these people were trying to save their families, their children, their infirm parents. ‘I looked myself up and down,’ he said, ‘and saw that I was saving only myself and my overcoat.’ Ashamed, he turned round and went back to his rooms. Subsequently, even during the fiercest bombing, he never left the house again. In September, fighting came to the city. ‘All the windows are wide open,’ he wrote in his diary. ‘Rifle fire fills every day. One goes into rooms on all fours like a bandit. There is only dry food to eat. There is little water and it must be saved, as must candles, as neither the water supply nor the power station is working.’ Liberation finally arrived in October 1944: the Red Army and the Partisans entered Belgrade, and Tito was installed as the head of a Communist-controlled government. In March 1945 The Bridge on the Drina was the first book published by Prosveta, the newly founded Serbian state publishing house. Successive editions sold out. Bosnian Chronicle followed later that year. In October 1961, Ivo Andrić was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. That he wrote two of his three great novels (the third being Omer Pasha Latas: Marshal to the Sultan) in such desperate conditions makes his accomplishment all the more extraordinary, and inspiring.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 73 © Tim Pears 2022

About the contributor

Tim Pears is the author of eleven novels, most recently the West Country Trilogy (2017–19) and the collection Chemistry and Other Stories (2021). He is very grateful to Celia Hawkesworth, Biljana Djordjević Mironja and Zoran Milutinović for their kind help with information for this essay. You can hear Tim Pears talking about his own novels on our podcast, Episode 19, ‘Tim Pears’s West Country’.