Until recently, my other half and I lived on site at a boarding-school in deepest, darkest Dorset. When severe snowstorms hit last year, closing local roads and downing power lines, the world beyond the school gates was summarily shut off. Although electricity in the main building was soon restored, thanks to an emergency generator, the same was not true for those of us living on the fringes of the estate: and at home, I faced the prospect of a very cold twenty-four hours until power would return.

It seemed as good a time as any to tackle what remained of my stack of Christmas books, and so, bundled in an unlikely assortment of layers, complete with babushka headscarf and mitts, I reached for a clothbound reprint of Geoffrey Pyke’s To Ruhleben – And Back.

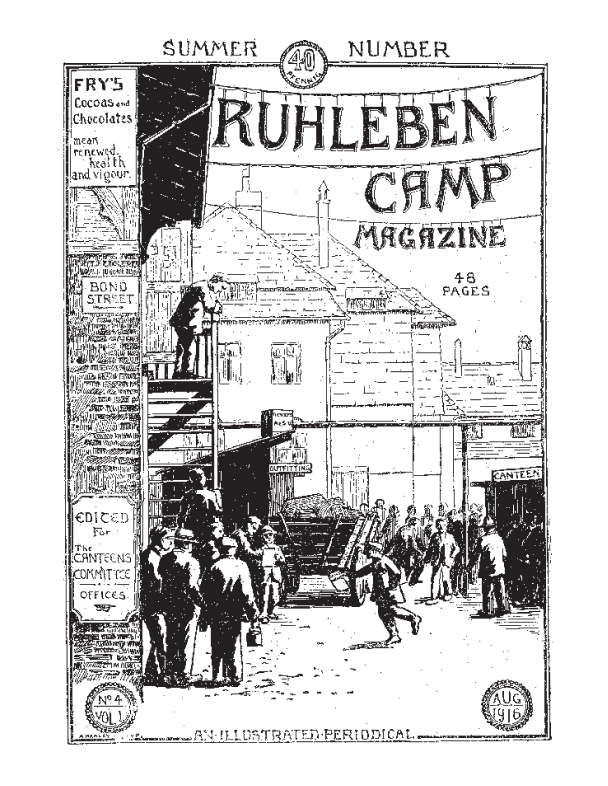

Published in 1916, the book was reissued in America in 2003 by the Collins Library, a project dedicated to the reprinting of unusual, out-of-print literary works. Part travelogue, part eyewitness account of one of Germany’s first and most notorious internment camps, it not only illuminates a largely overlooked moment in modern history but is also a gripping, at times darkly humorous tale told by one of the twentieth century’s most enigmatic personalities. Pyke’s is a ripping yarn of imprisonment and escape across hostile countryside, and I could have hoped for no better material with which to while away the hours in frozen isolation.

The author was just 20 and a student at Cambridge when he approached the Editor of London’s Daily Chronicle with the suggestion that they might like to make him their war correspondent in Berlin. Uninspired by his studies and unfit to join the military, Pyke had decided that he would become the only Englishman to infiltrate the German capital. To his surprise, the Editor agreed, and by September 1914 the young adventure-seeker was travelling across Europe on an American passport bought from a sailor.

It was a journey that makes today’s

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inUntil recently, my other half and I lived on site at a boarding-school in deepest, darkest Dorset. When severe snowstorms hit last year, closing local roads and downing power lines, the world beyond the school gates was summarily shut off. Although electricity in the main building was soon restored, thanks to an emergency generator, the same was not true for those of us living on the fringes of the estate: and at home, I faced the prospect of a very cold twenty-four hours until power would return.

It seemed as good a time as any to tackle what remained of my stack of Christmas books, and so, bundled in an unlikely assortment of layers, complete with babushka headscarf and mitts, I reached for a clothbound reprint of Geoffrey Pyke’s To Ruhleben – And Back. Published in 1916, the book was reissued in America in 2003 by the Collins Library, a project dedicated to the reprinting of unusual, out-of-print literary works. Part travelogue, part eyewitness account of one of Germany’s first and most notorious internment camps, it not only illuminates a largely overlooked moment in modern history but is also a gripping, at times darkly humorous tale told by one of the twentieth century’s most enigmatic personalities. Pyke’s is a ripping yarn of imprisonment and escape across hostile countryside, and I could have hoped for no better material with which to while away the hours in frozen isolation. The author was just 20 and a student at Cambridge when he approached the Editor of London’s Daily Chronicle with the suggestion that they might like to make him their war correspondent in Berlin. Uninspired by his studies and unfit to join the military, Pyke had decided that he would become the only Englishman to infiltrate the German capital. To his surprise, the Editor agreed, and by September 1914 the young adventure-seeker was travelling across Europe on an American passport bought from a sailor. It was a journey that makes today’s gap years pale by comparison. Having endured endless bullying at school for being not only a boffin but Jewish to boot, Pyke must have found the prospect of a solo mission exhilarating. ‘Little things such as the German military and the German police did not worry me,’ he writes, recalling the jaunty arrogance of a youth who had yet to experience the horror of war. Although prone to clever declamations on the nature of the conflict and its players (‘The difference between the tasks of the German and English Governments was that the first had to drive sheep and the second had to lead donkeys’), after just a few days in Berlin his ruminations take on a more ominous tone:As the realization began to dawn that he was up against a remarkable foe – at this stage, German morale was higher than the English knew – Pyke was apprehended and accused of being a spy. He was kept in solitary confinement for thirteen weeks. ‘Imagine walking up and down two and a half steps – five paces – and then back again,’ he writes. ‘Imagine doing this two dozen times, and then two thousand dozen times. It is not the months that count in solitary confinement, but the quarters of an hour.’ Mealtimes offered little in the way of relief:As I, an Englishman, sat there amid the great big turrets of flesh, a possible Daniel in a veritable den of lions, I saw how all the prophecies so nicely indulged in, in England were wrong. I saw those cropped heads, the skin just scintillating through the stubble, the two little compact ears, and at the back those great rolling waves of fat, that surmounting the top of the collar, lolled in great laps over the edge. I saw that a country that could support so much superfluous flesh at the back of its head could go on a long time before being forced to its knees and compelled to cry pax through want of sustenance.

The Germans are a wonderful folk, as most people agree. At breakfast they not only supplied me with bread made, not out of wheat, but out of potatoes, but also with coffee made, not out of coffee beans, but out of acorns. In fact, it can shortly be expected that they will create a substitute for water out of some other combination than that of two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen.Perhaps it is not so surprising, then, that he responded with relief when informed that he was to be sent to a prison camp. No matter that Pyke had no idea precisely what, or where, Ruhleben was: he would once again see other human beings and breathe fresh air. His jauntiness increased during his transfer, by train, to a holding facility outside Berlin. It was now that Pyke learned of official instructions being delivered to station masters across Germany: envelopes marked TO BE OPENED IN THE EVENT OF WAR WITH FRANCE were being replaced with ones marked TO BE OPENED IN THE EVENT OF WAR WITH RUSSIA. There was, apparently, a third – TO BE OPENED IN THE EVENT OF WAR WITH FRANCE AND RUSSIA. And yet, the author notes, ‘there was no fourth. No envelope with: TO BE OPENED IN THE EVENT OF WAR WITH FRANCE, RUSSIA, AND GREAT BRITAIN.’ And so Pyke arrived at the internment camp optimistic that things were about to get better. In fact, in many ways, they were about to get worse. Between 1914 and 1918, approximately 4,000 British civilians were held behind barbed wire in a converted racecourse in the suburb of Ruhleben (the name means ‘peaceful life’). The war had erupted so suddenly that there were still thousands of British businessmen, academics and visiting civilians in Germany on 4 August 1914; but instead of being deported, they had been herded into a camp which soon became notorious for its cramped conditions, inadequate rations and indifferent captors. Inmates were housed in stables where ‘the atmosphere was as thick as cheese’:

It was at this point in the story that I began to notice the cold again. After warming my hands over the stove and piling on another blanket, I rejoined young Geoffrey in his barracks, where a light snow had begun to seep through the roof. Here, for the first time, he saw war being waged against enemy civilians – not with guns, but through wilful neglect. In this purgatorial world of mud, open sewers and deep frost, Pyke himself succumbed to pneumonia and repeated bouts of food poisoning. There was, however, one advantage to living in such cramped quarters: class boundaries were almost entirely erased, leading inmates to collaborate in the development of a crude camp economy, as well as a borrowing library, orchestra and literary magazine – not to mention a performance of The Mikado pieced together entirely from memory. Thoroughfares were rechristened Marble Arch, Bond Street and Trafalgar Square, while a full schedule of goods and services was advertised on a central notice board:The whole place stank, and you could take the air, and cut it into chunks, throw it about and stamp on it, and yet it seemed about the same viscidity as mud . . . I reckoned that there was one half square inch of window space per man, and my own particular half square inch was eighteen feet away and round the corner.

Yet despite these diversions, Pyke soon developed itchy feet. Not inclined to wait out the war over games of bridge or tiddlywinks, he set about perfecting two methods of crawling in preparation for escape, not only from the camp, but from Germany. These he practised over several weeks (informing the wardens that the exercise had been suggested to him as a system for curing a weak heart) until he met a fellow inmate with whom he devised a plan to rival that hatched within Stalag Luft III. The pair’s earliest mooted strategies were, to put it mildly, rather far-fetched: smuggling a canoe to the Baltic coast; travelling concealed in a defunct boiler; assembling enough co-conspirators to pose as a travelling singers’ union. Fortunately, none of these schemes was attempted – and in the end it was a far more modest strategy that secured their escape. In the original edition of To Ruhleben – And Back, Pyke withheld a full explanation of this plan for fear that the German authorities might prevent other prisoners from escaping in the same manner: he wrote simply that ‘The plan was supremely obvious, and it remains there for any one of the denizens of Ruhleben whom it stares in the face, and who cares to take the risk.’ In the Collins Library reprint, the full details are divulged. Of course, this was only the beginning of the final phase of his adventure. Another escaped prisoner had taken a train across Germany only to be apprehended at the Dutch border. With this in mind, Pyke chose a rather more convoluted route – the details of which I will not reveal, as the pace and tension of the final pages constitute perhaps the most compelling part of the entire account, worth reading for the edge-of-your-seat closing paragraph alone. Geoffrey Pyke returned home a hero in 1915, and To Ruhleben was published the following year. His German escapade was to be but the first of many adventures that included the founding of the progressive Malting House School and, during the Second World War, designing landing craft employed at Normandy and snow vehicles used in the Arctic. Later, he became an advocate for UNICEF and Britain’s National Health Service and a vociferous critic of capital punishment. In 1948, however, Pyke committed suicide, which makes me wonder if he had been haunted by memories of his time in Ruhleben, by then recognizable as the blueprint for the concentration camps of the Second World War. It certainly seems a tragic end for a man of such vitality and ingenuity. Our power returned as I finished reading. Although few things could have raised my spirits more than the prospect of a hot bath, I was sorry to be jolted out of this very much colder world so soon. Pyke’s spirited account allowed me to revisit a particularly dark moment in history with fresh eyes and, although it is no longer possible to visit the camp at Ruhleben (now a sewage treatment plant), I shall certainly know which book to reach for when the next storm rolls in.Wanted: a copy of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and Pitman’s Ready Reckoner. Barrack 6. Have YOU had YOUR pipe carved as a memento to take HOME to YOUR friends? You should. Tom Noddy of Barrack 8 will do it for you just top hole. Prices moderate. Wanted: a teacher in Sanskrit. Apply Barrack 2, loft. The Lancastrian Association will meet at three o’clock on Wednesday at the right-hand top corner of the third grandstand.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 27 © Trilby Kent 2010

About the contributor

Trilby Kent worked in the Rare Books department at a London auction house before becoming a freelance journalist. Her first novel for children, Medina Hill, was published last year and her second, Stones for My Father, will appear in 2011.