American presidential memoirs have tended to be self-serving tomes, designed to massage reputations and secure their authors a fat windfall on retirement. This was not the case with the first, written by Ulysses S. Grant, who served two terms in the White House (1869–77). Grant does not write about his presidency but about his experiences as the victorious general of the Civil War.

An American friend of mine reads Grant’s Memoirs every year to remind him of an idealized expression of the American character personified by the old soldier: honest, straightforward, dogged, decent, loyal, self-effacing, courteous and tolerant. Non-Americans are also inspired by the story of a man who in early life failed at everything but who became one of history’s great generals.

As a lonely child Grant took refuge in horses, with which he had a natural empathy, and by the time he was 10 he had earned the reputation of someone who could perform equine miracles and ride horses considered impossible. But when, at 16, he was sent to West Point Military Academy, he showed so little aptitude for military tactics that he earned the nickname ‘Useless Grant’. Oddly enough, and in spite of a seemingly uncharacteristic penchant for reading romantic novels, it was at West Point that he laid the foundations of his literary style: clean, uncluttered prose that was clear and direct, if poorly spelt.

Not surprisingly, this retiring, taciturn youth had little success with women until he met the homely Julia who was to become his wife and soulmate. There was never a hint of scandal throughout their long, devoted marriage, although from the beginning Grant’s drinking was a problem. It took the form of solitary bingeing in a room with a bottle, followed by punishing hangovers that developed into migraines.

The Mexican-American War of 1846–8 was Grant’s first exposure to combat. He demonstrated his personal bravery and superb horsemanship when he volunteered to

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inAmerican presidential memoirs have tended to be self-serving tomes, designed to massage reputations and secure their authors a fat windfall on retirement. This was not the case with the first, written by Ulysses S. Grant, who served two terms in the White House (1869–77). Grant does not write about his presidency but about his experiences as the victorious general of the Civil War.

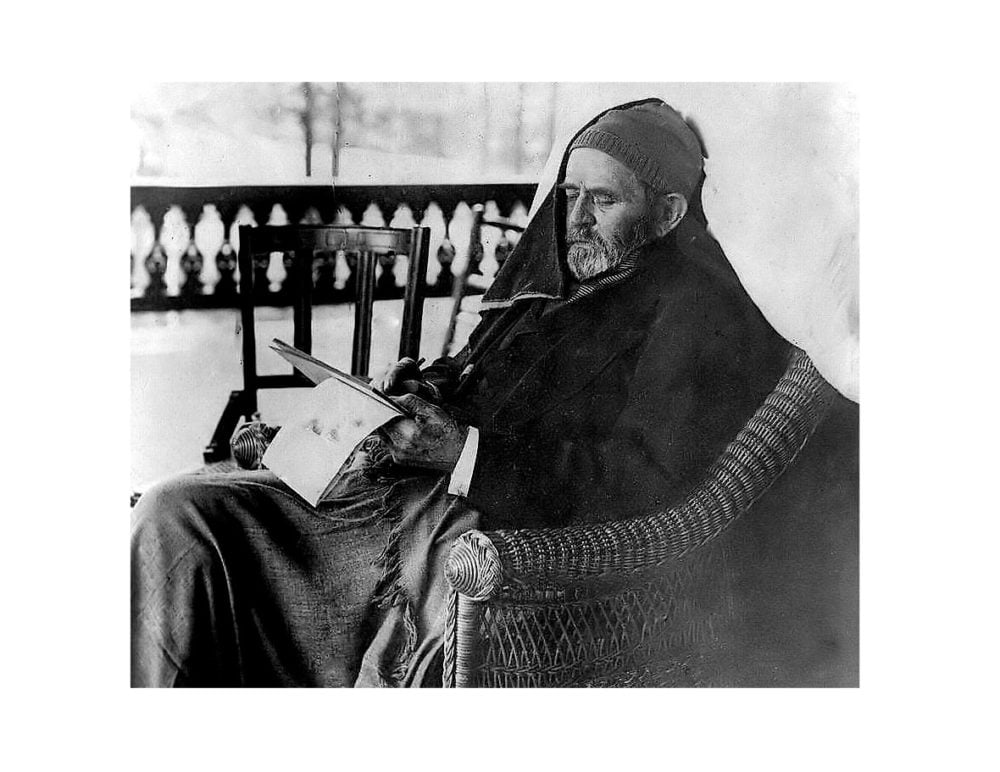

An American friend of mine reads Grant’s Memoirs every year to remind him of an idealized expression of the American character personified by the old soldier: honest, straightforward, dogged, decent, loyal, self-effacing, courteous and tolerant. Non-Americans are also inspired by the story of a man who in early life failed at everything but who became one of history’s great generals. As a lonely child Grant took refuge in horses, with which he had a natural empathy, and by the time he was 10 he had earned the reputation of someone who could perform equine miracles and ride horses considered impossible. But when, at 16, he was sent to West Point Military Academy, he showed so little aptitude for military tactics that he earned the nickname ‘Useless Grant’. Oddly enough, and in spite of a seemingly uncharacteristic penchant for reading romantic novels, it was at West Point that he laid the foundations of his literary style: clean, uncluttered prose that was clear and direct, if poorly spelt. Not surprisingly, this retiring, taciturn youth had little success with women until he met the homely Julia who was to become his wife and soulmate. There was never a hint of scandal throughout their long, devoted marriage, although from the beginning Grant’s drinking was a problem. It took the form of solitary bingeing in a room with a bottle, followed by punishing hangovers that developed into migraines. The Mexican-American War of 1846–8 was Grant’s first exposure to combat. He demonstrated his personal bravery and superb horsemanship when he volunteered to run the gauntlet during fighting in Monterrey to fetch fresh ammunition. Clinging to the side of his horse with one arm around its neck and one foot draped over the saddle, he rode through a hail of bullets at full gallop. Nevertheless, he thought the war ‘one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation’, and his descriptions of the beauty and grandeur of the country in his Memoirs are in sharp contrast to his disgust with the way the US Government treated Native Americans. The experience bred in him a lifelong antipathy to war. When peace returned, Grant endured a series of dead-end, solitary postings all over the US. Separated from his wife, he was bored and lonely, and his drinking attracted the attention of senior officers. Eventually he was forced to resign from the Army. It was the first of a string of humiliations. Grant now threw all his energy into a variety of ventures, all of which failed. Eventually he was forced to return to work in his father’s store in Galena, Illinois. The Civil War changed Grant’s destiny. Recalled to the Army with the rank of Colonel – though he had neither horse nor uniform until a fellow merchant in Galena stumped up for them – he was put in charge of a volunteer rabble that he quickly disciplined into a model regiment. The man who had failed at everything was turning into a formidable commander of men and would eventually become a general of rock-like confidence. In his muddy boots and black slouch hat, Grant certainly never looked like a general. He always wore a private’s uniform with only a general’s shoulder tabs to distinguish him. He saw no glamour in combat and felt deeply for the dead and wounded on both sides. He understood the price in blood and misery that victory would demand yet knew that the only purpose of a battle was to win. The scale of slaughter in the Civil War was first demonstrated at the Battle of Shiloh. It claimed more lives than all previous American wars combined – 30,000 killed, wounded or missing – and it shocked the world. The press, which had always slandered Grant as a drunk, now called him a butcher. The tag stuck and it hurt, but as the war continued and he won battle after battle he was transformed from butcher to victor. One of my favourite passages in the Memoirs is the description of Grant accepting the surrender of the Confederate Army’s General Robert E. Lee. Grant rode over to the small house where Lee was installed, arriving as muddy and shabby as ever. Lee, on the other hand, was every inch the General, immaculate in a pale grey uniform with gold braided sleeves, a scarlet sash around his waist, a sword hanging at his side. Grant had left his sword behind – it got in the way when riding, he explained. The admiration Grant felt for Lee almost amounted to a sense of awe and he did not attempt to hide it. As the staff prepared the surrender documents, the Generals chatted about the Mexican War and mutual military acquaintances. (Lee might have been surprised to learn that one of Grant’s most trusted staff officers was a Native American.) Grant became so absorbed in the conversation that Lee finally had to remind him of the business at hand. Grant did not ask for Lee’s sword and added a sentence to the terms of the surrender allowing Confederate officers to retain their side-arms, horses and baggage to avoid unnecessary humiliation. Lee was moved by the gesture. Later, he admitted with embarrassment that his men were starving. Grant immediately agreed to provide 25,000 rations. The following day he rode over again for a long, friendly conversation with his defeated adversary. The war was over, but it had devastated large areas of the country and killed 625,000 Americans – far more than the United States lost in the Second World War. To add to the trauma President Abraham Lincoln was now assassinated. Grant became the obvious choice for the Republican nomination. He accepted and promptly returned to Galena where his stature was such that he was elected President without going on a campaign tour, making speeches or even appearing much in public. He was to serve two terms in the White House, and from the beginning his critics accused him of being unschooled in government and ignorant of economics. He was certainly a poor politician, and the White House was rocked by a string of financial and political scandals during his incumbency. As a man of absolute integrity himself, Grant was incapable of detecting dishonesty in those close to him. However, the esteem in which he was held, coupled with his obvious decency, did help to heal the wounds of a nation bloodied and shaken by a terrible war. He brought the South back into the Union and kept America out of two potential foreign wars. Upon leaving the White House, the President and his wife did not lose their taste for living in style and mixing with the rich and powerful, but there was scant income to support such an expensive life. Money was raised by public subscription to provide the Grants with an annual income. Grant invested it in Mexican railroad bonds, the railroads defaulted and the money was lost. Grant now decided, implausibly, to make his fortune on Wall Street. Buck Grant, the President’s son, had gone into business with a bright young man with the idea of investing money raised from Civil War veterans. With the General as a front, money poured in. The idea was a good one but unfortunately Buck was as big a fool in business as his father. Worse, his partner was a ruthless conman, the Bernie Madoff of his day. He was simply running a Ponzi scheme, using new investments to deliver profits to previous investors, and stealing the rest. When the scheme eventually collapsed, Grant was left ruined and bitterly humiliated. Mark Twain then suggested that Grant write his memoirs and offered to become his publisher, giving a generous advance and share of the profits. The Memoirs naturally became one of the seminal works of the American Civil War. For me, though, the story of the writing of the book is equally gripping. Before Grant started work he was diagnosed with throat cancer. The diagnosis was a death sentence at the time, guaranteeing a difficult and painful end, but Grant was determined to finish the book before he died. The composition was as brave and arduous an undertaking as any of his military campaigns. He wrote every word himself and used his phenomenal memory instead of a team of researchers to reconstruct with precision each and every battle of the Civil War. Despite being in constant pain, he methodically turned out twenty to fifty pages a day. There is a wonderful photograph of him at work, wrapped in a blanket with a woollen cap on his head, sitting on his porch in winter in a wicker chair, writing on a pad, pencil in gloved hands. Grant began the book in late 1884 and finished it in July 1885, five days before his death. Mark Twain immediately knew that he had a great book on his hands. He compared the Memoirs to Caesar’s Commentaries:Unlike modern publishers, Twain did not expect the book to sell itself. An army of 10,000 door-to-door salesmen was recruited, many of them veterans dressed in uniform, and households were offered a wide choice of variously priced bindings. Excluding the Bible, it became the best-selling book in the history of America. The Memoirs have been praised ever since. Even the waspish and anti-military Gore Vidal was an admirer: ‘It is simply not possible to read Grant’s memoirs without realizing that the author is a man of first-rate intelligence . . . his book is a classic.’ At the very end of the Memoirs, with Grant only days from death, this man of war who had failed at everything but soldiering wrote:Clarity of statement, directness, simplicity, unpretentiousness, manifest truthfulness, fairness and justice toward friend and foe alike, soldierly candour and frankness, and soldierly avoidance of flowery speech. A great, unique and unapproachable literary masterpiece. There is no higher literature than these modest simple memoirs . . .

I feel we are on the eve of a new era, when there is to be great harmony between the Federal and the Confederate. I cannot stay to be a living witness to the correctness of this prophecy; but I feel it within me that it is to be so. The universally kind feeling expressed to me when it was supposed that each day would prove my last, seemed to be the beginning of the answer to ‘let us have peace’.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 36 © Christopher Robbins 2012

About the contributor

Christopher Robbins is currently writing Blood, Oil and Pomegranates: In Search of Azerbaijan, Land of Fire.