I spend a couple of weeks each year walking on the Lake District fells, so it is inevitable that I should have fallen upon James Rebanks’s remarkable The Shepherd’s Life (2015). I loved it, and I learned much more about upland sheep farming than I could possibly have divined from hours of watching Herdwicks on the fell. Reading The Shepherd’s Life inevitably set me thinking about another book I read long ago and which, tellingly, turned the young Rebanks into a reader: ‘One day, I pulled A Shepherd’s Life by W. H. Hudson from the bookcase . . . It was going to be lousy and patronizing, I just knew it. I was going to hate it like the books they’d pushed at us in school. But I was wrong, I didn’t hate it. I loved it.’

The use of the indefinite article in Hudson’s title points to an important difference between the two books, however. Hudson was less interested in conveying the practicalities of shepherding and sheep-breeding than in recording the lives of shepherds. His is a much gentler and more episodic book than Rebanks’s but, nevertheless, it’s one I’ve never forgotten.

Readers of Slightly Foxed will have noticed quite a strong bias towards writers of well-written pastoral non-fiction, such as Adrian Bell, Ronald Blythe, Richard Hillyer and Richard Mabey. This is scarcely surprising since in this country we seem to have a predilection for reading about our countryside and the people who live in it. This preoccupation goes back at least to the time of the Romantic poets and William Cobbett, when burgeoning towns and cities seemed to be eating up the countryside, but it was promoted by the quickening pace of life at the beginning of the twentieth century, when educated people began to see that the valued ‘old ways’ were threatened, especially by the motor-car. It was at this point that William Henry Hudson, an extremely accomplished field naturalist, began visiting Wiltshire and the surrounding counties and getting to know country dwellers and the wildlife that co-existed with them.

Strangely, Hudson was not bred in England. His Devonian grandfather had settled in New England, but his parents decided to try their luck as sheep-farmers in Argentina, not far from Buenos Aires, and that was where Hudson was born in 1841. His father was declared bankrupt at least once, so they moved around and times were apparently often hard. Hudson seems to have spent a great deal of his childhood out of doors, minutely observing the natural world, and by the time he moved to London in 1874 he was already an expert on South American birds.

In London he married his much older landlady, who ran a couple of boarding-houses, but she too became bankrupt, so the hard times continued. It was a number of years before Hudson was recognized as a writer: for novels such as Green Mansions, books on the natural history of both Britain and Argentina, and memoirs of his early life ‒ Long Ago and Far Away, The Naturalist in La Plata and Idle in Patagonia. He wrote a couple of dozen books in all. He was also one of the first chairmen of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

Along the way, he acquired influential literary friends, among them George Gissing and Sir Edward Grey (the greatest ornithologist ever to have been Foreign Secretary) who in 1901 lobbied successfully to get Hudson a pension. Thereafter he could more easily afford to travel, choosing particularly the West Country, moving about on foot or bicycle, and crucially getting away from the city, which he loathed. The result of these wanderings were books of natural history, including Afoot in England, Birds in Town and Village, Hampshire Days, Nature in Downland and, his most famous, A Shepherd’s Life, subtitled Impressions of the South Wiltshire Downs.

Hudson, bred to the pampas with its almost endless horizons, seems to have been particularly taken by Salisbury Plain, or at least the downland on the southern border of it, which had not been colonized by the Army. In A Shepherd’s Life he describes lovingly the chalk downs, the green and wooded valleys, and the clear streams of the Wylye, the Avon and the Nadder. The central figure in this landscape is a picturesque old man called Caleb Bawcombe, the pseudonym Hudson chose for a retired head shepherd from a hilltop village he calls Winterbourne Bishop – in fact, Martin on the Hampshire/Wiltshire border. Over a period of time, Hudson got to know Caleb well and heard tales of shepherds and shepherding stretching as far back as 1830.

Hudson’s tone is often elegiac: the great bustard was already extinct, and animals and birds, as well as the country folk, were now barred from many woods by Edwardian landowners determined to preserve their pheasant shoots. Hudson rarely has a good word to say about them or their tenants since, as far as he is concerned, they were both exploiters of the landless labourer. He is also vitriolic about Victorian judges who hanged or deported poachers and sheep-stealers and those members of the starving peasantry who were caught breaking up threshing machines.

His choice of a hill shepherd to tell tales of the countryside is not surprising. Shepherds get the most favourable press in the Bible, and ever afterwards have been admired for their sagacity, strength of character and practical expertise – the result of using their sharp eyes on long, lonely vigils. Hudson certainly believed there was a very particular wisdom in shepherds, whom he plainly considered the aristocracy of agricultural labourers: they might earn no more than seven shillings a week, but they were entrusted with valuable stock by their employers and left alone to get on with it. And he admired their inevitably close partnership with that most intelligent of dogs, the Border Collie sheepdog, which can only work well for a master who has considerable patience and understanding.

I was at first struck by Caleb’s appearance, and later by the expression of his eyes. A very tall, big-boned, lean, round-shouldered man, he was uncouth almost to the point of grotesqueness . . . The hazel eyes were wonderfully clear, but that quality was less remarkable than the unhuman intelligence in them – fawn-like eyes that gazed steadily at you as one may gaze through the window, open back and front, of a house at the landscape beyond.

The book is not all about this shepherd. Hudson also got to know a number of gipsies, whom he liked and admired for their knowledge of natural things, as well as their contempt for a settled life, but about whose attitudes to other people’s property he had few illusions.

Hudson was fascinated by what were once called ‘old characters’, people without schooling or who had left school before they were fully formed, and so went their own way, acquiring in time the gnarled and individual personality of an old oak. Unlettered, they often had a particular richness of speech, both in phrase-making and rhythm, since it was their only means of communication. (Hudson marvels at how, though the Bawcombe family are scattered, they never think to write letters to each other.) I lived in Wiltshire for a time in the mid-1970s and worked on Saturdays with a semi-retired gardener, who used to say about our task of pruning the roses: ‘We do be going to nip them climbers.’ The rhythms of rural Wiltshire speech therefore have an especial appeal for me, and in A Shepherd’s Life they are fully on display.

To Hudson, what Caleb had found was a land of lost content. Right at the end of the book he reports him as saying: ‘I don’t say that I want to have my life again, because ’twould be sinful. We must take what is sent. But if ’twas offered me and I was told to choose my work, I’d say, Give me my Wiltsheer Downs again and let me be a shepherd there all my life long.’ Though Hudson is chronicling a life of serenity that he contrasts starkly with that lived by those who crowd together in cities, it would not be fair to call him a sentimentalist (even if many of his followers were). He knew how hard and boring and unrewarding manual labour mostly is, but he also saw how it could forge stout-hearted and admirable, if narrow, characters.

Over the forty or so years since I last read A Shepherd’s Life, it has lost a little of its charm for me. Hudson is not a particularly elegant stylist, and a few of the stories trail off into inconsequentiality. Lovers of wild flora and fauna will find Hudson’s Hampshire Days (about the New Forest) a more satisfactory read, since it shows how careful and observant a naturalist he was.

Each man kills the thing he loves, and the way of life that Hudson chronicles – very hard, very poor, and sometimes downright cruel, but rich in texture, and with its own rewards – could not survive urban man’s hankering after the countryside. As soon as he was prosperous enough to own a motor-car, he invaded that countryside and chased out its poorer, long-established inhabitants. What the commuter did not do, changes in agriculture, especially during two world wars, achieved. Employed upland shepherds have mostly gone, and those who survive do so in part thanks to the taxpayer. At the turn of the last century, they needed a Hudson to tell their story; these days, they tell their own.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 53 © Ursula Buchan 2017

About the contributor

Ursula Buchan is an enthusiastic but woefully amateur and ignorant field naturalist.

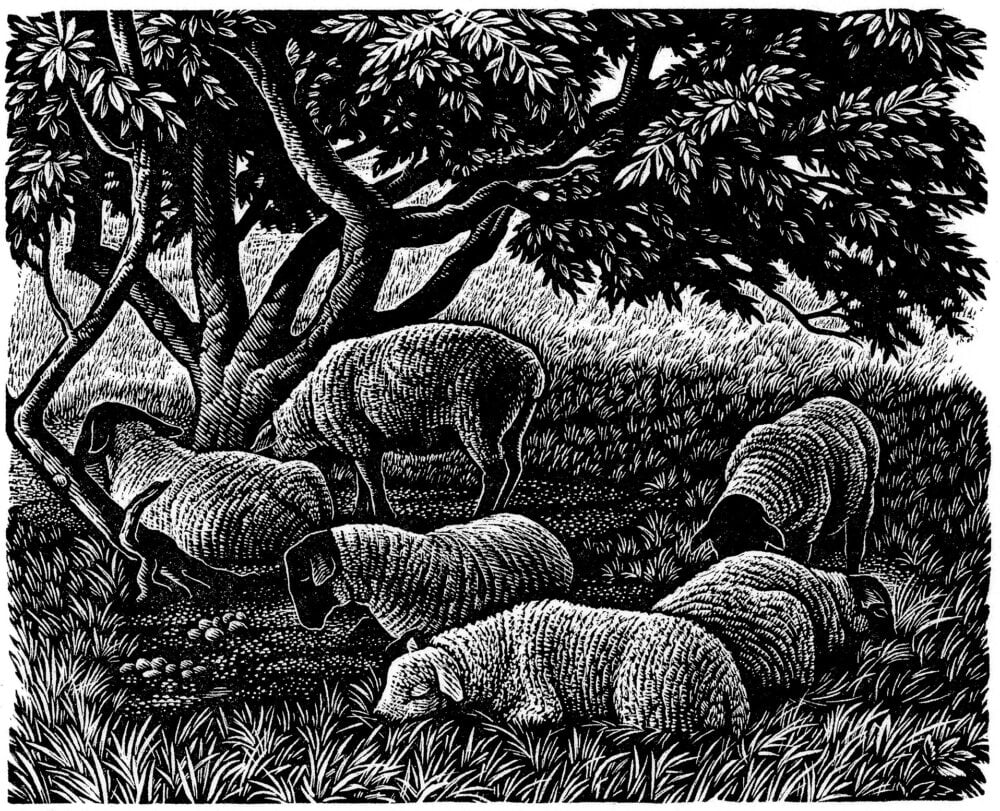

Wood engraving by Howard Phipps.