Some days, the longing to re-experience childhood is so strong I imagine it might actually happen. My longing is not whimsical nostalgia: childhood happiness was shot through with anxiety about upsetting nanny, my father or God. So while sometimes I would like to be a child again, my real longing is to re-experience first readings of now familiar books. I’d willingly trade a week of old age to recapture first encounters with Heathcliff, Mr Rochester, Mary Poppins, Ken McLaughlin and Flicka; first glimpses of Narnia, Gormenghast and Malory Towers. I’d trade more than an hour to open, with no fore-knowledge, The Once and Future King. I’d trade nothing, though, to re-experience the delight of discovering Violet Needham’s The Black Riders (1939). No need. The delight has never left me.

The first in Violet Needham’s Ruritanian, or Stormy Petrel, sequence, The Black Riders is set in a fictional Central European empire. Though I’d never been to Austria, I imagined it to be similar; friendlier and tidier than my bleak familiar Lancashire moors. Where we had dishevelled farmyards, derelict gates and rusting baths as water troughs, in ‘the Empire’ farms were cosy, gates swung briskly and baths were found indoors. It was discouraging to realize that though I longed to be wild as Emily Brontë’s Catherine Earnshaw, I was actually more like Needham’s Antoinette, Countess of Valsarnia, alias Wych Hazel, whose nerves undermine her best conspiratorial intentions. I didn’t like the discovery, but I kept reading.

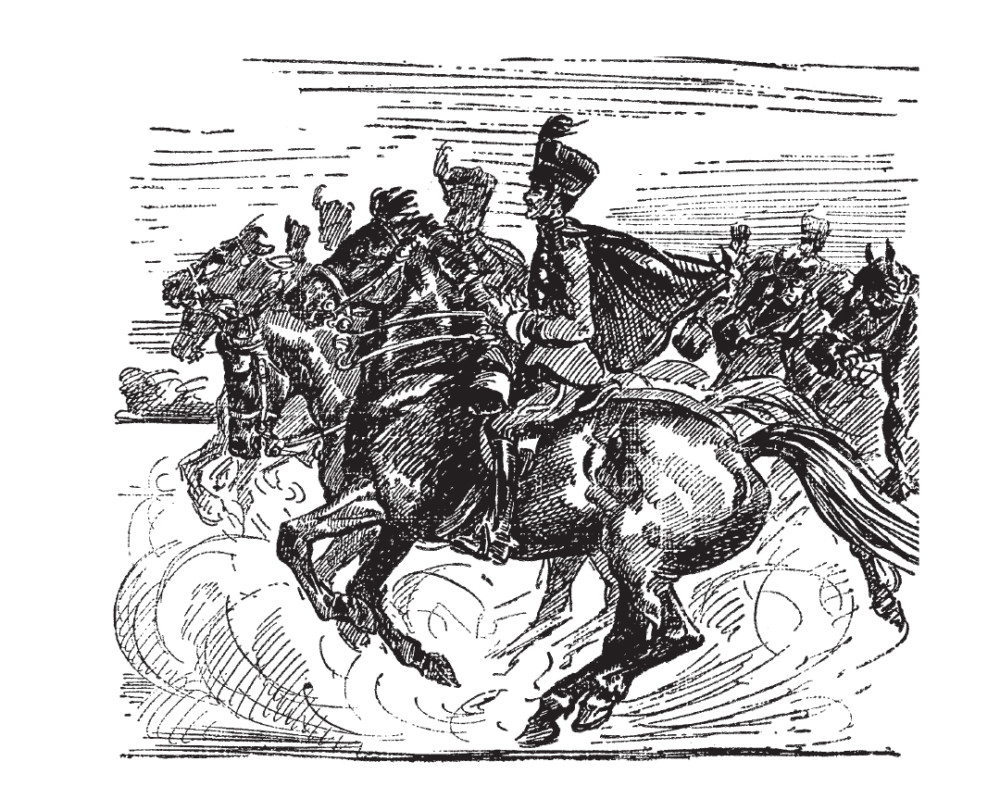

The Black Riders of the title form part of the imperial army. ‘Magnificent men they were,’ Needham writes, ‘in black uniforms, riding magnificent black horses; not a speck of colour anywhere about them, black tunics and breeches, black saddle-cloths and bridles, black astrakhan busbies with black aigrettes; only the steel of bit and stirrup shone like silver.’ Magnificence and threat are a potent mix and,

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inSome days, the longing to re-experience childhood is so strong I imagine it might actually happen. My longing is not whimsical nostalgia: childhood happiness was shot through with anxiety about upsetting nanny, my father or God. So while sometimes I would like to be a child again, my real longing is to re-experience first readings of now familiar books. I’d willingly trade a week of old age to recapture first encounters with Heathcliff, Mr Rochester, Mary Poppins, Ken McLaughlin and Flicka; first glimpses of Narnia, Gormenghast and Malory Towers. I’d trade more than an hour to open, with no fore-knowledge, The Once and Future King. I’d trade nothing, though, to re-experience the delight of discovering Violet Needham’s The Black Riders (1939). No need. The delight has never left me.

The first in Violet Needham’s Ruritanian, or Stormy Petrel, sequence, The Black Riders is set in a fictional Central European empire. Though I’d never been to Austria, I imagined it to be similar; friendlier and tidier than my bleak familiar Lancashire moors. Where we had dishevelled farmyards, derelict gates and rusting baths as water troughs, in ‘the Empire’ farms were cosy, gates swung briskly and baths were found indoors. It was discouraging to realize that though I longed to be wild as Emily Brontë’s Catherine Earnshaw, I was actually more like Needham’s Antoinette, Countess of Valsarnia, alias Wych Hazel, whose nerves undermine her best conspiratorial intentions. I didn’t like the discovery, but I kept reading. The Black Riders of the title form part of the imperial army. ‘Magnificent men they were,’ Needham writes, ‘in black uniforms, riding magnificent black horses; not a speck of colour anywhere about them, black tunics and breeches, black saddle-cloths and bridles, black astrakhan busbies with black aigrettes; only the steel of bit and stirrup shone like silver.’ Magnificence and threat are a potent mix and, though that’s the longest mention they get, the Black Riders stalk the reader just as they stalk the novel’s young hero. Twelve-year-old Dick Fauconbois is drawn into a rebel confederation whose cause, unfashionably, isn’t democracy in the empire, only better imperial government. Not politics but conflicted loyalties are centre- stage here. Dick’s father, now dead, was a Black Rider. Dick longs to follow in his footsteps yet before the first chapter is out, the Black Riders are Dick’s enemies. His new father figure, the marvellously named confederate leader Far Away Moses, so-called because ‘when my enemies look for me I am always far away’, is a quieter kind of influence. Under his gentle tutelage, Dick exchanges the freedom of ordinary life for life undercover, delivering vital messages between confederates, his methods of travel – on foot, by train, barge, fast car, sledge, caravan and even skates – pitching the reader between the pre- and post-industrial worlds. Cliffhangers abound: can Dick, nicknamed Stormy Petrel by the secret police, survive the sword-thrusts through the brushwood under which he is hidden? Can he burn the confederates’ papers in time? Has he given too much away to Nicholas the Shepherd? Will lovely Wych Hazel crack under pressure? Can Judith, the feisty little daughter of the ruthless, charming and unimpeachable Count Jasper the Terrible, save Far Away Moses from the firing squad? But the plot, for all its masterly pace and excitement, is the least of it. We neither know nor care much about the ideology that drives Far Away Moses. Instead the novel taps into the perennial childish fear of not measuring up. When Far Away tells Dick that ‘before the end’ he will have to do things that will ‘sear your spirit, not your flesh’, I was terrified, not that Dick would die, but that he would let his friends down. Coming, as I do, from a family whose ancestors sacrificed all to uphold what they considered the ‘one, true religion’, this fear felt personal. Faced with abjuring my faith, I was pretty sure I’d be found wanting. I dreaded this failure for Dick. And it’s not quite what happens: it’s worse for being more tangled. After some vicissitudes, Dick, now Count Jasper’s prisoner, is offered a bargain. In exchange for the confederates’ names, Jasper will free Far Away Moses from the life imprisonment which is, for Far Away, worse than death. Dick’s response haunted me for years: ‘Can one do one’s country a good service by betraying one’s friends and going back on one’s word of honour?’ As if that wasn’t drama enough, by this time I was secretly in love with Count Jasper. Only later did I realize that in this I was at one with the author. In my imagination, and perhaps in Violet Needham’s, Count Jasper looked like a young Omar Sharif and had a similar effect. We weren’t alone. The novelist and poet Michèle Roberts, like me brought up a Catholic, describes how the book ‘both turned me on and made me feel guilty. Secret pleasure reading it; secret guilt.’ Perhaps that’s part of the novel’s enduring appeal: the older you is reminded not only of being tucked up on the sofa, book glued to hands, but also of early disconcerting stirrings in hitherto unexplored parts of the body. A late developer, I think my stirrings were only in my head. Though the masculine glamour of Count Jasper invaded my dreams, I was actually mostly with Dick, learning the meaning of loyalty ‘with bitter knowledge’. Violet Needham was 63 in 1939 when this, her first book, was published, a time when the gender stereotypes of dominant men and fluttery women were still perfectly acceptable. Since my own family was hobbled by male primogeniture, the stereotypes were familiar and, so I thought then, unchallengeable. Years later, I should have come to regard the whole Ruritanian series as a historical relic: distinguished but outdated. Yet dismissal was impossible. Needham’s mindset might be dated – Dick thinks nothing of taking a baby squirrel from its nest or catching moths – but what a storyteller she was! Eschewing comic-book heroes and villains, she paints, with perfect perspective and in clear language, a muddled, emotionally complicated world into which any child of any time or place might imagine him or herself. Like us, Dick is not impossibly brave: he cries and makes mistakes. Wych Hazel’s feelings for Count Jasper mirror those of Michèle Roberts ‒ secret pleasure and secret guilt. Both Count Jasper and Count St Silvain (Far Away Moses’s real name) are honourable men facing the consequences of troubling decisions. Gender roles in The Black Riders might be problematic to modern editors but the novel’s dilemmas endure. And Needham has much to teach modern writers about neither over-egging the pudding nor describing for description’s sake. ‘Perfect obedience,’ Far Away Moses replies softly to ‘no one in particular’ when, after professing total obedience to confederate orders, Dick questions being sent to bed. Dick goes very red and runs out of the room. Needham says nothing more. Behaviour is allowed to speak for itself. With the same economy, the ‘scented gloom of the pine forests’, the ‘great chestnut woods’ and the ‘broad plain, golden with harvest and cut with the silver ribbon of the mighty river’ serve to make doubly dreadful the prospect of civil war’s killing fields; Dick’s grey and steadfast eyes connect him to his dead father; and the grand gloom of the Citadel from which Count Jasper conducts state business contrasts with the chintz curtains and gay wallpaper of the nursery at Souvenir, the grand house the Count shares with his daughter. No words are wasted. Sometimes Needham’s grown-up voice intervenes, as in Dick’s ‘poor little head’, but these moments are few. More often, the author shares her shivery delight in ciphers, codes, notebooks and map tracings; the nervous romance of wrapping reports in oiled silks and secreting them under a jacket; the boredom of waiting and the terror of muddling a secretly agreed exchange of words. Along with Dick, I copied maps on tracing paper, thrilling to its flimsy crackle under my pencil, before folding the tracings into notebooks. Where Dick had Far Away and, eventually, a graceful bay mare called Sweetbriar, I had my dog and a stocky piebald gelding called Mischief. Best of all, there’s a word which, once heard, always means The Black Riders. The word is, of course, the confederates’ password: ‘fortitude’. Those three syllables struck readers’ hearts very particularly at the time of the book’s publication and continue to strike readers’ hearts today. We all know what fortitude means. We all know its worth. Even now I never hear the word or use it without also hearing Far Away saying, ‘Should you be walking in the street, and a passer-by bend down and whisper “fortitude”, you must leave whatever you are doing and do as the speaker bids you.’ As yet, nobody has ever whispered ‘fortitude’ to me, but I’m always waiting and just hoping I’ll be up to my task.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 53 © Katie Grant 2017

About the contributor

Katie Grant, author, columnist and Royal Literary Fund Consultant Fellow, wishes she had one name. Untidily, she has three: Katie Grant (for everyday), K. M. Grant (for children’s and young adult fiction), and now Katherine Grant, the name under which her latest novel, Sedition, is published.