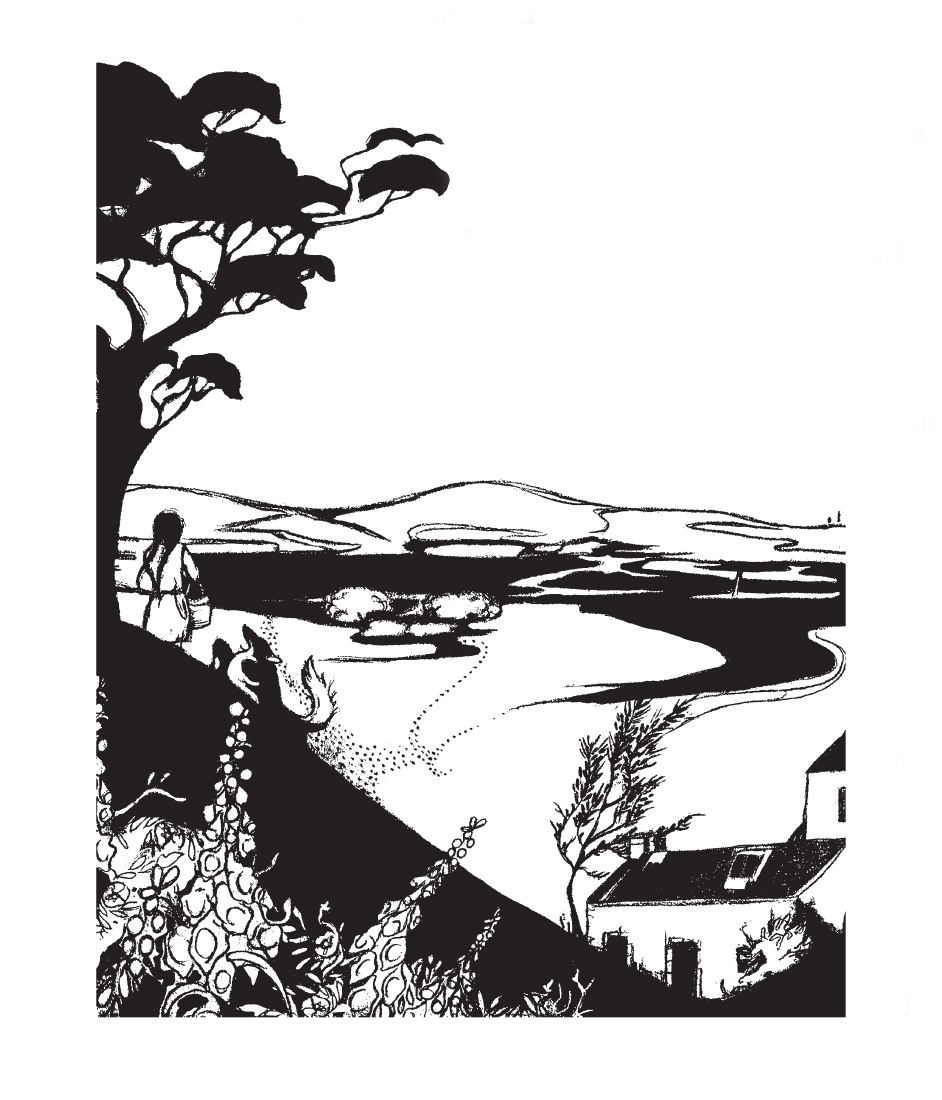

Reachfar is a ruin now. Approach, as we did, from the north, across rough, boulder-strewn fields, and it has a blind, sad look, just one small window in its long stone front. Go round to the other side and the mood changes. You are greeted by a blaze of gorse and a yard that has reverted riotously to moorland. Only a stone trough remains. But, for all its decay, the croft has a companionable air, although parlour, kitchen and attics are now all one and ivy pushes its way in over crumbling sills.

Reachfar, as it was in its bustling heyday, is the heart of Elizabeth Jane Cameron’s first book, My Friends the Miss Boyds. I came across it when I was still at school, reading everything I could lay hands on as long as it wasn’t one of my A-level set texts. For a Buckinghamshire girl who had never been further north than Rhyl, the portrayal of life in a remote, closely knit Highland community was bewitching, a glimpse of an unguessed-at world.

Narrated by 8-year-old Janet Sandison, the novel has immense vitality. An only child growing up at Reachfar in the First World War, Janet observes unfolding events with a wit and fierce intelligence inherited from her elders. When the local town of Achcraggan is invaded by a covey of Miss Boyds, a discordant note enters the even tenor of country life. Their desire to show how things are done in sophisticated circles in Inverness and their determination to catch a man – any man – provokes widespread amusement, masked by inscrutable Highland politeness. But, as the war ends, irresistible comedy gives way to an Ophelia-like tragedy. Though life returns to its normal rhythms and everyone but Janet seems to have forgotten Miss Violet Boyd, profounder changes loom: economic depression will threaten the rural way of life in a way that the foolish Miss Boyds never did.

The book carries unshakeable conviction: this is a writer who knows her landscape and people intimately. Indeed, Cameron is drawing a map of th

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inReachfar is a ruin now. Approach, as we did, from the north, across rough, boulder-strewn fields, and it has a blind, sad look, just one small window in its long stone front. Go round to the other side and the mood changes. You are greeted by a blaze of gorse and a yard that has reverted riotously to moorland. Only a stone trough remains. But, for all its decay, the croft has a companionable air, although parlour, kitchen and attics are now all one and ivy pushes its way in over crumbling sills.

Reachfar, as it was in its bustling heyday, is the heart of Elizabeth Jane Cameron’s first book, My Friends the Miss Boyds. I came across it when I was still at school, reading everything I could lay hands on as long as it wasn’t one of my A-level set texts. For a Buckinghamshire girl who had never been further north than Rhyl, the portrayal of life in a remote, closely knit Highland community was bewitching, a glimpse of an unguessed-at world. Narrated by 8-year-old Janet Sandison, the novel has immense vitality. An only child growing up at Reachfar in the First World War, Janet observes unfolding events with a wit and fierce intelligence inherited from her elders. When the local town of Achcraggan is invaded by a covey of Miss Boyds, a discordant note enters the even tenor of country life. Their desire to show how things are done in sophisticated circles in Inverness and their determination to catch a man – any man – provokes widespread amusement, masked by inscrutable Highland politeness. But, as the war ends, irresistible comedy gives way to an Ophelia-like tragedy. Though life returns to its normal rhythms and everyone but Janet seems to have forgotten Miss Violet Boyd, profounder changes loom: economic depression will threaten the rural way of life in a way that the foolish Miss Boyds never did. The book carries unshakeable conviction: this is a writer who knows her landscape and people intimately. Indeed, Cameron is drawing a map of the part of her childhood she loved best, her school holidays at her grandparents’ croft, the Colony, her ‘real home’. The croft, the countryside and the hard, satisfying, self-sufficient life provide the setting and dictate the pace of the story – just as the eccentricities of her family and friends colour it, and her own early fascination with words lends freshness to the telling. The Colony stands high on the northern flank of the Black Isle. Despite its name, the Black Isle isn’t an island at all but a peninsula just north of Inverness, between the Moray and Cromarty Firths. Tiny, attractive towns dot the coast, while behind them rises moorland. The area was known to relatively few until My Friends the Miss Boyds took the literary world by storm in 1959. Cameron had written it (and six other books) while living in Jamaica with her partner Sandy. She kept her writing secret, hiding the manuscripts in her linen cupboard and only seeking a publisher when Sandy became seriously ill. Publishing history was made when Macmillan accepted all seven. Back in the UK after Sandy’s death, she became a reluctant overnight celebrity. I’d wanted to visit the Black Isle ever since I first read the book but it was to be nearly forty years before I did so. In the late spring of 2008, two old university friends, Christine, who is married to the author’s nephew Neil, Kate, a writer, and I arranged a long weekend there. We were to stay in the cottage in Jemimaville that Cameron shared with her Uncle George when she returned from Jamaica. I was thrilled but apprehensive. The once best-selling Miss Boyds was long out of print and I wondered if the places it brought so triumphantly to life would still be there. They were. We walked up to the Colony on our first morning, leaving the sparkling blue of the Cromarty Firth below us. A narrow path led us through dappled woodland and swathes of bluebells, past broken, mossy walls and a silent, reed-filled lake, until the way was barred by impenetrable thickets and we were forced to wriggle through barbed wire and negotiate ploughed fields to reach our goal. Bypassing the byre and stepping inside the living quarters, we found remnants of mottled plaster clinging to the rough stones, deep slots where attic floor beams had rested, a battered frame askew in the small north window. Against one wall was the rusting kitchen range where poor, mad Miss Violet Boyd sat docilely while Grandmother and Lady Lydia admired her dead rabbit ‘baby’. Next, Christine drove us along the shore road to Cromarty, the real-life Achcraggan. Today the little town, with its plain, pleasing Georgian houses, bright gardens and short streets seeming to end in the sea must still look much as it did a hundred years ago. Any visiting Miss Boyds fans will, I promise, feel a surge of delighted recognition as they wander round. Here is the pier where the coal boat arrived once a year (a great event, for it always carried interesting extras along with the official cargo); here the maze of whitewashed cottages in Fisher Town, where ‘the brown-faced, sloe-eyed, barefoot’ fish-seller Bella Beagle lived; here the sea wall where the six Miss Boyds sat giggling as a destroyer dashed in with news that the Great War was finally over; and here the long white inn where the child of shame ‘Andra’ Boyd made his reappearance as a fully fledged spiv in the 1940s. By some miracle, the early twentieth century has survived into the twenty-first. Beside the sea, a sweep of close-cropped turf leads to a tall, gaunt stone, a memorial to those driven out by the Clearances – still fresh in sheep-hating Grandmother’s folk-memory. On the hill above is the church where the black-bearded Reverend Roderick battled against his congregation’s tendency to sin. Many Camerons are buried here but not Elizabeth Jane. To find her grave, you must return along the shore road to the inner curve of Udale Bay. Here, in a tranquil graveyard by the ruins of Kirkmichael church, a simple headstone looking over the water to Jemimaville records the nom de plume by which readers all over the world knew her: Jane Duncan.* * *

That evening, as we sat nursing glasses of wine by a log fire in Rose Cottage, Christine remembered her aunt-in-law’s papers stacked in the cupboard under the stairs. Enthralled, we dragged the boxes through to the little sitting-room and began to delve. Brown-paper parcels tied up with string held typescripts of her published books; torn manila envelopes bulged with early, unpublished writing. A stack of business-like desk diaries were filled with brief, telling entries of her post-war life in Jamaica and Jemimaville; earlier fragments tucked into an exercise book gave tantalizing glimpses into her time in the WAAF. And fat scrapbooks, assiduously assembled by Uncle George, contained reviews of her books – an impressive reminder of the impact she made. By the time she died in 1976, Jane Duncan had written more than thirty books, translated into several languages, and acquired an eager readership around the world. Besides the first seven My Friends titles accepted in a batch by Macmillan, she wrote a dozen more in the sequence. The novels mirror the progress of her own life, from secretary- companion in 1930s England (My Friend Muriel ) to the WAAF and early married life (My Friend Monica), the gorgeous, alien environment of the Caribbean (My Friend Sandy and others) and the return to the Black Isle. In all of them, autobiography and imagination are blended in a witty, acerbic, compassionate mix uniquely her own; in all of them Reachfar, whether physically present or not, is an underlying force, the enduring standard by which she measures the outside world. The three of us read and drank and talked far into the night, astonished that a writer with such a distinctive voice had been allowed to fall out of print. We found her birth certificate. It was, we discovered, less than two years until her centenary. We resolved that something must be done.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 35 © Vivien Cripps 2012

About the contributor

In 2010, as part of the Jane Duncan centenary celebrations, Vivien Cripps’s publishing house Millrace brought out a new edition of Jane Duncan’s My Friends the Miss Boyds (1959) (Pb • 288pp • £12.50 • isbn 9781902173313). Reviews and reactions that summer showed that her writing has not lost its appeal. In 2011 Millrace also reissued My Friend Monica (1960) (Pb • 272pp • £12.50 • isbn 9781902173320).