The dog pricked up his ears, which was surprising because so far he hadn’t seemed all that bright. Vanya and I turned to look. At the edge of the clearing a man in a white woollen suit was just visible against the snow, returning our stares and clasping a rifle. For half a minute or so nobody moved or spoke. Vanya’s gun was out of reach, leaning against a tree stump. All around us the forest gaped. Apart from the crackle of twigs we were burning to ward off frostbite, silence reigned – and all waited to see if there would be blood.

The Bilimbé, the Lifudzin, the Sanhobé, the Iman; sometimes it’s the exotic sounds of places that turn a book into an inspiration. For me it was partly the names of these remote river systems and partly the excitements of Russia’s Far Eastern forests through which they course and where Vladimir Arseniev’s Dersu the Trapper is set that made them so irresistible I had to see them for myself.

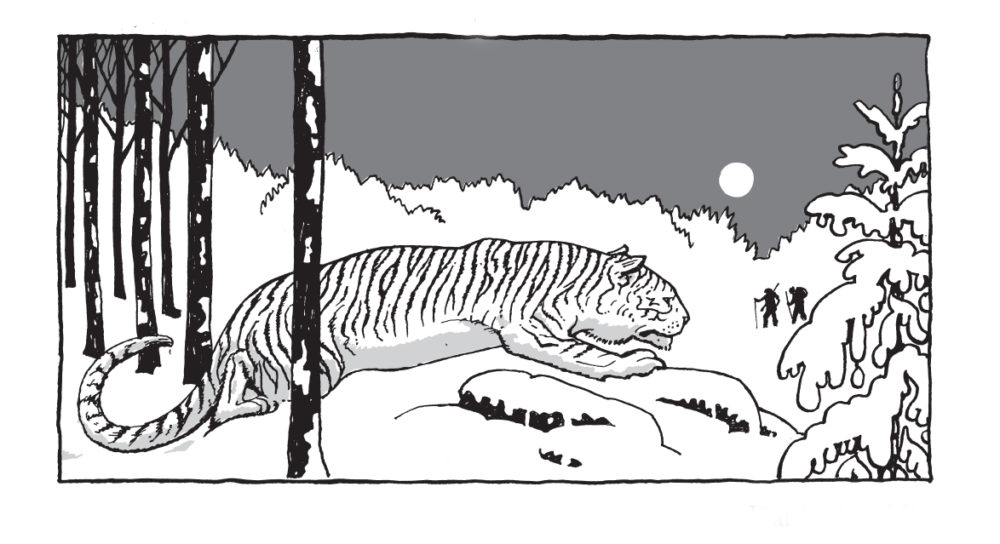

Vanya, a descendant of Dersu’s tribe, was a squirrel hunter and we had walked up a frozen stream through ancient stands of pine in search of his quarry. Fearsome big predators – Siberian tigers and brown bears – were nearby, but as Arseniev tells us in his little known classic of adventure in remotest Siberia, ‘in the taiga . . . the most dangerous meeting of all is with a man’.

In 1902 Vladimir Arseniev was a 30-year-old captain in the Russian army. He had been posted to the Russian Far East to conduct military surveys of a mountain range called the Sikhote-Alin which was awash with bandits, ginseng hunters, native fur-trappers and ferocious wild animals. His orders were to reconnoitre thousands of kilometres of ridgelines and riverbeds to prepare for war with Japan, but Arseniev got hooked on wilderness adventure, and it took over his life.

Over the next twenty-five years, Arseniev led twelve major geographical expeditions and wrote sixty works on the nature and people of a densely forested region

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe dog pricked up his ears, which was surprising because so far he hadn’t seemed all that bright. Vanya and I turned to look. At the edge of the clearing a man in a white woollen suit was just visible against the snow, returning our stares and clasping a rifle. For half a minute or so nobody moved or spoke. Vanya’s gun was out of reach, leaning against a tree stump. All around us the forest gaped. Apart from the crackle of twigs we were burning to ward off frostbite, silence reigned – and all waited to see if there would be blood.

The Bilimbé, the Lifudzin, the Sanhobé, the Iman; sometimes it’s the exotic sounds of places that turn a book into an inspiration. For me it was partly the names of these remote river systems and partly the excitements of Russia’s Far Eastern forests through which they course and where Vladimir Arseniev’s Dersu the Trapper is set that made them so irresistible I had to see them for myself. Vanya, a descendant of Dersu’s tribe, was a squirrel hunter and we had walked up a frozen stream through ancient stands of pine in search of his quarry. Fearsome big predators – Siberian tigers and brown bears – were nearby, but as Arseniev tells us in his little known classic of adventure in remotest Siberia, ‘in the taiga . . . the most dangerous meeting of all is with a man’. In 1902 Vladimir Arseniev was a 30-year-old captain in the Russian army. He had been posted to the Russian Far East to conduct military surveys of a mountain range called the Sikhote-Alin which was awash with bandits, ginseng hunters, native fur-trappers and ferocious wild animals. His orders were to reconnoitre thousands of kilometres of ridgelines and riverbeds to prepare for war with Japan, but Arseniev got hooked on wilderness adventure, and it took over his life. Over the next twenty-five years, Arseniev led twelve major geographical expeditions and wrote sixty works on the nature and people of a densely forested region which lies waist-deep in snow in winter, and steams with humidity and biting flies in summer. Yet despite his prolific output, the defining moment of Arseniev’s life was meeting Dersu Uzala, an ageing member of a dwindling indigenous furtrapping tribe known as the Golds.Dersu had survived a serious mauling by a tiger and lived on his own in the forest, carrying only a knapsack made of birch bark. He knew the taiga intimately, and Arseniev hired him as guide on two military surveying expeditions into the Sikhote-Alin. In the book Arseniev frames his friendship with Dersu as lasting for three expeditions spanning six years, beginning in 1902. The purpose of this literary free-handedness (Arseniev and Dersu Uzala in fact did not meet until 1906) is to cast the literary Dersu as hero. Initially Arseniev finds the pidgin-speaking man curious, almost laughably so. Dersu talks to the plants and animals as if they’re people, even addressing the sun as a man. Slowly, however, his appreciation of Dersu’s qualities changes as he learns from the native’s view of nature a wisdom crucial to his survival:His weather-beaten face was typical . . . with high cheekbones, small nose, slanting eyes with the Mongolian fold of the lid, and broad mouth with strong, big teeth. Most remarkable of all were his eyes . . . dark grey . . . Through them looked out upon the world directness of character, good nature, and decision.

The green colour of the sky turned to orange, then to red. As a closing phenomenon the purple-red horizon darkened, as though by smoke. Simultaneously with the sunset, on the east appeared the shadow of the earth . . . I gazed in admiration, but at that moment heard Dersu grumble: ‘Me think will be big wind.’In describing a beautiful sunset, Arseniev demonstrates the richness of his prose. His technique – repetitive imagery and sounds – is lullingly poetic and has purpose, for the taiga is so full of such soul-drenching visions of nature that this is the only way to describe it. In the same moment, Arseniev stresses the reality – that Dersu knows much more about it than he. The next day, Dersu’s prediction comes true, and the two men are caught in a cataclysmic storm on a lakeshore bedevilled with shifting sands. During the storm the Captain passes out from hypothermia while Dersu frantically cuts reeds to build a shelter. Even though it probably never took place, this act saves Arseniev’s life, and in writing about it as if it were true Arseniev sets up an unshakeable, archetypal bond between two unlikely friends. From this moment, the romance of the book becomes clear. Dersu the Trapper is not only the fable of a heroic and noble savage, it also encapsulates a distant, nigh-unreachable land which Arseniev desperately wants to protect. Evocative illustrations and mouth-watering maps make Arseniev’s faraway idyll irresistibly seductive. The impenetrable taiga, like the endless grassy steppe and the inhumane tundra, is something that feels inherently Russian, colours on the palette of a vast psychological Motherland. And yet it is foreign too. In Arseniev and Dersu’s time the Sikhote- Alin were full of non-Russians. The Trans-Siberian railway had only recently arrived, and although it would transform the landscape irrevocably, the hills were still wild, and most of their inhabitants were Chinese, Korean or of native origin. During his years of exploration, Arseniev developed a potent dislike for the activities of these first two peoples. Unlike Dersu’s kind, who would harvest from the forest only what they needed to survive, Arseniev saw the Chinese and the Koreans as dangerously wasteful and exploitative. Were he to know that these two nations (along with Russia) are today responsible for the continued depletion of the forests Arseniev cherished so dearly, he would no doubt be doubly incensed. This degradation includes sustained poaching of one of its rarest and most symbolic inhabitants, the Siberian tiger. Arseniev constructed his book with respect for the environment as his primary goal. After the storm by the lake, he and Dersu part company, but some years later they reunite delightedly to embark on long travels together through the taiga. Once again Dersu saves the Captain’s life, carrying him across a river to escape a forest fire. ‘Enormous cedars, gripped by the flame, were burning like colossal torches. Everything was burning, grass, fallen leaves, trunks, logs, stumps. We could hear living trees groan and burst from the heat.’ Other terrifying perils await them, including a charging bear and flash floods. On a third expedition the men are forced to winter in the forest in almost unimaginably cold and harsh conditions. But most poignant of all is the day when Dersu’s eyesight fails him. This physical deterioration marks the end of his days as a hunter, and Arseniev insists he come to live in his apartment in the city. Like most wild beings, Dersu adapts poorly to urban life. Dismayed at not being able to go shooting in the park and incredulous that anyone should pay money for firewood, he has soon had enough and returns to his forest abode. This end to their friendship marked Arseniev deeply, so he set about finding a way to commemorate Dersu and the nature he had taught Arseniev to love. The result is the book Dersu the Trapper. Arseniev died prematurely in 1930, while under arrest and accused of being a Japanese spy. Had he lived longer he would certainly have met a more sinister fate. His widow was executed after a trial lasting just ten minutes in the Vladivostok cells of Stalin’s secret police, and their daughter was sent to the gulag for fifteen years. Although Arseniev was initially discredited under Stalin, his reputation was later revived to espouse Soviet ideals which Arseniev himself would have vehemently disliked. Nowadays in the Russian Far East Dersu the Trapper is regarded as a children’s book rather than as the journey towards environmental wisdom that Arseniev had intended. Free from historical associations, it may be easier for an outsider to read Arseniev this way. I travelled to follow in his footsteps, and found much of his world under threat of eradication. The forests of the Sikhote-Alin are still dangerous, but their most lethal adversary now is man himself.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 31 © Patrick Evans 2011

About the contributor

Patrick Evans is on the hunt for more Russian adventures.