Mountaineers can obviously take a joke. In 1981, four years before W. E. Bowman died and a quarter of a century after the publication of his spoof mountaineering book, The Ascent of Rum Doodle, he discovered to his amazement that members of the 1959 Australian Antarctic Expedition had affectionately named a small mountain Mount Rumdoodle and that this had been duly incorporated into Antarctic maps.

Travelling recently from London up to Scotland, I took with me a paperback reissue of his book to read on the train. I was going to visit my daughter, Sophie, who has relocated from London to Argyll and now lives in a cottage surrounded by mountains. Most of these are Munros (named after Sir Hugh T. Munro who in 1891 surveyed all of Scotland’s mountains over 3,000 feet). It is a place of wild waterfalls, wind and fast scudding clouds, and her kitchen cupboards are full of ropes and rock-climbing tackle. I thought she would enjoy Bowman’s book and planned to make her a present of it, but first I was keeping up the family tradition of book-giving: well-thumbed and with a bookmark still inside.

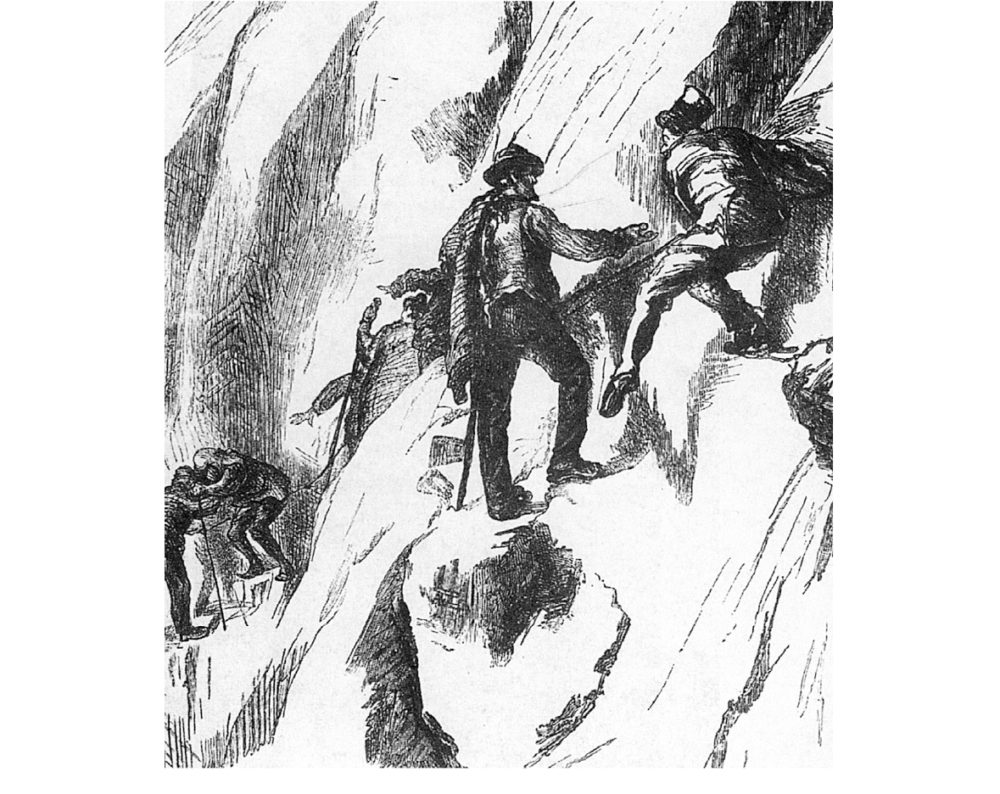

The new Rum Doodle contains an introduction by Bill Bryson and plenty of delightful illustrations featuring old engravings and possibly genuine photographs of mountaineering exploits, suitably

recaptioned with quotes from the book. Soon I was chuckling and smiling, not something I usually do on trains – all the way up, in fact, until we passed through the Lake District. There I laid down the book, not because it had in any way palled, but because I find it impossible to pass mountains without giving them my attention.

As a child, I lived in a grey granite house on the edge of the Cairngorms. In front of the house, across the road, was a municipal park with asphalt paths and tidy lawns but if you squeezed through

a gap in the railin

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inMountaineers can obviously take a joke. In 1981, four years before W. E. Bowman died and a quarter of a century after the publication of his spoof mountaineering book, The Ascent of Rum Doodle, he discovered to his amazement that members of the 1959 Australian Antarctic Expedition had affectionately named a small mountain Mount Rumdoodle and that this had been duly incorporated into Antarctic maps.

Travelling recently from London up to Scotland, I took with me a paperback reissue of his book to read on the train. I was going to visit my daughter, Sophie, who has relocated from London to Argyll and now lives in a cottage surrounded by mountains. Most of these are Munros (named after Sir Hugh T. Munro who in 1891 surveyed all of Scotland’s mountains over 3,000 feet). It is a place of wild waterfalls, wind and fast scudding clouds, and her kitchen cupboards are full of ropes and rock-climbing tackle. I thought she would enjoy Bowman’s book and planned to make her a present of it, but first I was keeping up the family tradition of book-giving: well-thumbed and with a bookmark still inside. The new Rum Doodle contains an introduction by Bill Bryson and plenty of delightful illustrations featuring old engravings and possibly genuine photographs of mountaineering exploits, suitably recaptioned with quotes from the book. Soon I was chuckling and smiling, not something I usually do on trains – all the way up, in fact, until we passed through the Lake District. There I laid down the book, not because it had in any way palled, but because I find it impossible to pass mountains without giving them my attention. As a child, I lived in a grey granite house on the edge of the Cairngorms. In front of the house, across the road, was a municipal park with asphalt paths and tidy lawns but if you squeezed through a gap in the railings, you could climb up a hill covered with blaeberries and harebells. At the summit someone had built an octagonal pagoda – Scotland, contrary to its dour image, is full of strange fancies and follies – and I used to sit up there, under the gilt roof, gazing across to the rim of blue hills in the distance, where there was snow even in summer. It was in 1956, three years after the first ‘conquest’ of Everest, that W. E. Bowman published his book. His imaginary mountain, in its mysterious snowy fastness, has never been climbed before. Binder, the narrator, tells us: ‘The various estimates of the height of the true summit vary considerably, but by taking an average of these figures it is possible to say confidently that the summit of Rum Doodle is 40,000 and a half feet above sea level.’ The highest hill Bowman himself ever climbed was Scafell Pike (3,208 feet). He was born in 1911 in Scarborough, North Yorkshire, left school at 16 and spent much of his life in a drawing office as a civil engineer. According to his widow, Eva Bowman, his book was modelled on a 1937 account of Bill Tilman’s Nandi Devi expedition. Nevertheless, many readers believed him to be a famous mountaineer writing under a pseudonym. Surely no amateur could have written so amusingly about the real rigours of climbing? The Ascent of Rum Doodle is crammed with references to equipment and apparatus (including crates of top-quality champagne, for medicinal purposes), the descriptions of gorges, crevasses and precipitous ridges are entirely convincing, and there is much talk of summits, faces, saddles, Base Camp, Advanced Camp, the South Col and the Wall. It is not, however, the location that has made the book such an enduring cult classic, but its cast of likeable and eccentric characters, all as idiotic as Bertie Wooster, but somehow more touching and human in their fallibility. As Bill Bryson explains in his Introduction:There is Binder, the kindly, dogged, reliably under-insightful leader of the party; Jungle the route finder who cannot find his way to any assembly point and is forever cabling apologies from remote and inappropriate locales; Wish, the scientist, who passes the sea voyage by testing his equipment and discovers that the ship is 153 feet above sea level; Constant, the language expert who, through errors of grammar and syntax, constantly provokes to fury the Yogistani porters; and the terrifying cook Pong, whose arrival at each camp spurs the men on to ever greater heights.Pong’s cooking not only gives the men indigestion (much is made of cramps, stomach aches, nightmares, belches, pills and tablets) but is considered by its creator to be an art form: at any hint of criticism ‘he went into a kind of frenzy and threatened us with knives’. In addition, the men are prone to a series of mysterious ailments – valley lassitude, glacier lassitude, Base Camp lassitude, Italian measles, altitude deafness and vertigo, among others – but of course there is always that ‘medicinal’ champagne to hand and, as you would expect, disaster follows on from disaster. In spite of everything, Binder never fails to see his companions in a good light. Even when six members of his expedition, after a series of mishaps and contrived blunders, find themselves at the bottom of a crevasse and radio a request for champagne – what else? – Binder, teetering on the edge and peering down, tantalized by the mysterious sound of distant singing (‘Oh my darling Clementine’), rejoices that his companions have not lost heart, speculates that the singing could be a coded message, and gives thanks that his team are in good spirits in a situation of great peril. Needless to say they are retrieved later by the Yogistani porters, Bing, Bung and Bang. ‘I comforted myself ’, says Binder, ‘with the thought that our suffering was not yet over; and as I followed the happy and united party I was cheered by the reflection that our friendship had been tempered into bonds of steel by the perils we faced together. I was tasting the keener rewards of leadership.’ Although Bowman’s book is a brilliantly sustained parody, a gentle lampooning of all those virtues that mountaineering might be said to engender, it does direct the reader, over and over again, to one central, perplexing question: why exactly are they doing this? The ‘because it’s there’ answer is patently insufficient. Arriving in Glencoe, I found Sophie waiting for me. ‘I can’t believe you’ve never been up a Munro,’ she said. Shaking my head weakly, I tried to look game. Close to hand (or should that be boot?) was the Pap of Glencoe, Buchaille Etive Mòr and a host of lesser-known peaks, with Ben Nevis, the tallest of them all, just around the corner. Thankfully, during my visit it was unusually hot – in fact much too hot for an unfit Londoner like me to attempt a climb. The nearest we came to it was a stroll through Glen Nevis. There, at the base of the Ben, we found the Three Peaks Challenge under way. This involves climbing (otherwise known as ‘bagging’ in mountaineering parlance) Ben Nevis, Scafell Pike and Mount Snowdon in twenty-four hours, including driving time between peaks. The tweed jackets, corduroy trousers and wooden walking-sticks of Binder’s team had here given way to Gore-Tex, carbon fibre and polymer fleece, but the gung-ho atmosphere was pure Bowman. We watched the Challengers set off, then took a narrow rockstrewn path along the gorge beside the river. As we walked, Sophie told me about the proposed clean-up of the Ben. There was to be a removal of cairns – at the last count thirty-five – and other assorted memorial stones, plaques and urns filled with the ashes of loved ones and pets. The mountain had become a repository for memories, a place of tribute and pilgrimage. And that wasn’t all. Climbers had become used to picking their way through discarded crisp packets, bottles and chocolate wrappers, but now there was even a piano on the top. Checking this out later, I found an article from The Scotsman. ‘Our guys couldn’t believe their eyes,’ said one of the clean-up volunteers. ‘At first they thought it was just the wooden casing – but then they saw the whole cast-iron frame complete with strings.’ The mystery was solved when a veteran charity fundraiser told the newspaper that this was in fact his organ which he had carried single-handedly to the summit. He added that he had played ‘Scotland the Brave’ on it and had also taken up a plough, a gas cylinder and a barrel of beer. Others have taken up a wheelbarrow and a bed. For charity of course. Bowman’s mountaineers don’t carry objects for charity. They hire porters to carry their baggage. As the team arrive at Chaikhosi, where they are to commence their expedition, they are astonished and initially gratified to see that a vast crowd has gathered to welcome them. Although only 3,000 porters are required, 30,000 porters have turned up. It seems that the Yogistani word for three is identical to the word for thirty, ‘except for a kind of snort in the middle which is, of course, impossible to convey by telegram’. On the subject of porters, Binder says: ‘There can be no doubt that the Yogistani is a natural mountaineer. When he becomes sufficiently civilized and educated to climb mountains voluntarily he may well be unapproachable.’ In fact it is the porters who succeed in climbing Rum Doodle, while Binder and the rest of the team, inevitably, climb the wrong mountain. During the Second World War, Bowman served with the RAF in Egypt. Afterwards he became a pacifist. He was a thinker and an idealist who wrote: ‘Justice can be neither defined nor achieved: it can only be pursued, by infinitely delicate adjustment, of man to man in friendship.’ I wonder what he would have felt about the British Army’s recent advertising campaign featuring a real-time attempt by some of its soldiers to climb Mount Everest, a campaign which, according to at least one commentator, explains why the Army is currently ahead of its recruitment targets. There is a mountain behind my mother’s house in the Southern Uplands that I have climbed approximately every decade of my life. It’s nowhere near a Munro, but from its whale-backed summit, covered in summer with purple heather, you can see the Lake District and the Isle of Man. The last time I went up it was with Sophie. We were cat-sitting my mother’s bad-tempered ginger tom while she holidayed in Crete. Figuring that the cat could manage a night on its own, we set off, taking with us a packet of sandwiches, a bottle of wine and a tent. We sat up there and watched the sun go down. The tent flapped manically around us and at times I thought the wind would lift it right up and blow us away. In the morning we watched the sun rise, then dark clouds swept towards us from the west and we made our way down. Looking up at Rum Doodle before attempting the final ascent, Binder says: ‘In such moments a man feels close to himself. We stood there, close to ourselves, until sunset, the supreme artist, touched the snowfields of that mighty bastion with rose-tinted brushes and the mountain became a vision such as few human eyes have beheld.’ Maybe, clichés aside, Binder has supplied an answer. It is not ‘because it’s there’ but because we are. We do it for others – for the dead and the living, in an attempt to connect with lost time and the spirits of the departed. We climb mountains in teams and with friends or family. They bring us together and this is indeed what happens at the end of the book; the team unite for the first time, rally round and drink a toast to Binder, in cocoa – the champagne having already been consumed.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 14 © Linda Letherbarrow 2007

About the contributor

Linda Leatherbarrow is the author of a collection of short stories, Essential Kit, in which there is some mention of Gore-Tex, but none of ropes or ice-axes.