The pub was at the end of an ill-lit side street. Under the back bar’s nicotine-stained ceiling, half a dozen sombre-faced men sat round a table and planned to set the world free from capitalism. It was winter, 1963; I was 18 and had been drawn here by the rumour of free beer for student recruits to the Party. It soon became clear that these men were in no way bloody revolutionaries – the Party was dedicated to peaceful persuasion, by the distribution of leaflets and patient argument. I couldn’t help thinking, as I looked at their faces, that we were few and mankind many. The meeting was long, serious and very dull. The most surprising thing, as we prepared to depart, was a warning by the chairman (a revolving position to guard against temptations of Stalinism) to watch out for police surveillance. We were advised to leave the pub one by one and at intervals and to take a roundabout route to our bus stops. Outside it was raining. I was a bit drunk on free beer but failed to detect any operatives of Special Branch as I swayed homeward.

When, a few years later, I started to read G. K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday, I thought how feeble we were as revolutionaries compared to the seven anarchists of that book – at the beginning of the book anyway, for it has many surprises up its sleeve. Of all of Chesterton’s stories this novel, published in 1908, is the most fantastic and ultimately mysterious. Chesterton was profoundly religious and politically conservative, and he regarded with horror a world in which, as now, revolutionaries demanded attention by indiscriminate bombings and assassinations.

We are in the London suburb of Saffron Park, at the end of a summer’s day. The evening sky is suffused with a peculiar and slightly menacing light: the brick-built houses are ‘as red and ragged as a cloud of s

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe pub was at the end of an ill-lit side street. Under the back bar’s nicotine-stained ceiling, half a dozen sombre-faced men sat round a table and planned to set the world free from capitalism. It was winter, 1963; I was 18 and had been drawn here by the rumour of free beer for student recruits to the Party. It soon became clear that these men were in no way bloody revolutionaries – the Party was dedicated to peaceful persuasion, by the distribution of leaflets and patient argument. I couldn’t help thinking, as I looked at their faces, that we were few and mankind many. The meeting was long, serious and very dull. The most surprising thing, as we prepared to depart, was a warning by the chairman (a revolving position to guard against temptations of Stalinism) to watch out for police surveillance. We were advised to leave the pub one by one and at intervals and to take a roundabout route to our bus stops. Outside it was raining. I was a bit drunk on free beer but failed to detect any operatives of Special Branch as I swayed homeward.

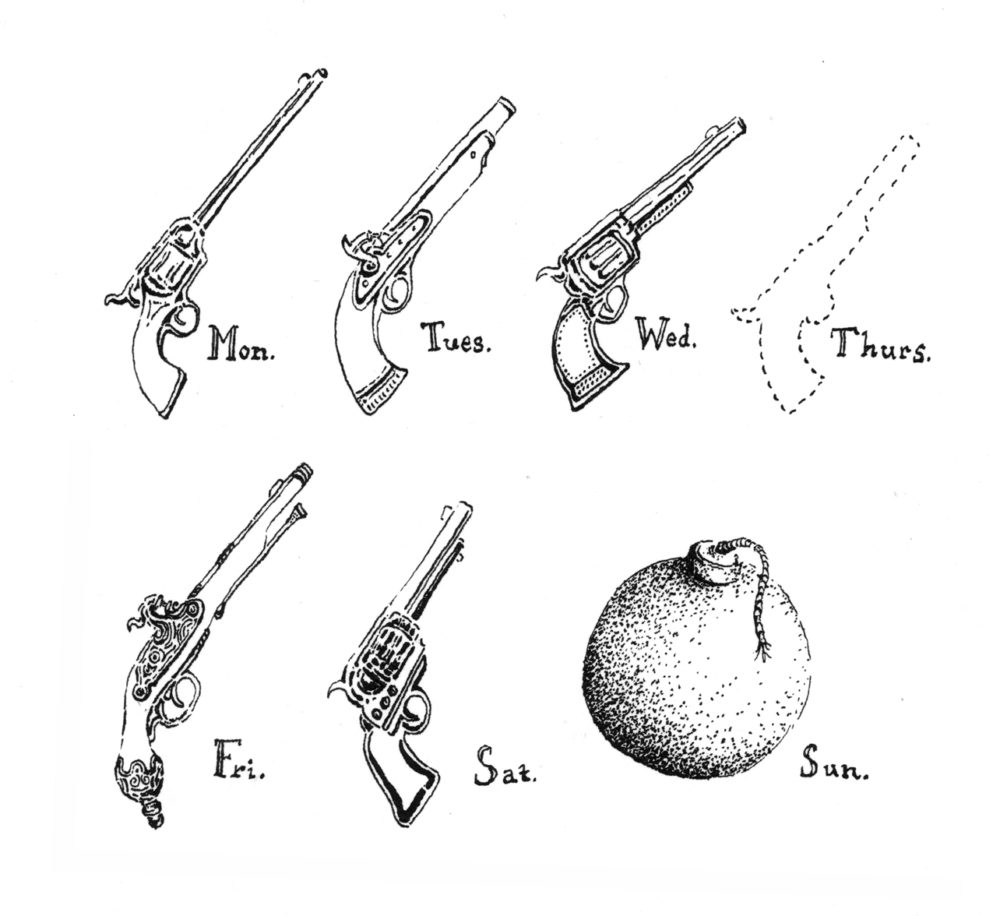

When, a few years later, I started to read G. K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday, I thought how feeble we were as revolutionaries compared to the seven anarchists of that book – at the beginning of the book anyway, for it has many surprises up its sleeve. Of all of Chesterton’s stories this novel, published in 1908, is the most fantastic and ultimately mysterious. Chesterton was profoundly religious and politically conservative, and he regarded with horror a world in which, as now, revolutionaries demanded attention by indiscriminate bombings and assassinations. We are in the London suburb of Saffron Park, at the end of a summer’s day. The evening sky is suffused with a peculiar and slightly menacing light: the brick-built houses are ‘as red and ragged as a cloud of sunset . . . the extravagant roofs dark against the afterglow’. At a party in one of the gardens, two poets, Gabriel Syme and Lucian Gregory, are locked in argument. Gregory is an indifferent poet but an anarchist who holds that ‘The man who throws a bomb is an artist . . . he sees how much more valuable is one burst of blazing light, one peal of perfect thunder than the mere common bodies of a few shapeless policemen.’ Syme disagrees vehemently and insults Gregory by pointing out the absurdity of preaching revolution in an English suburban garden. The guests gradually disperse, until Syme is left alone. What follows is ‘so improbable, that it might well have been a dream’. Outside, in the starlit street, Gregory is waiting for Syme. Their argument flares up again and, irritated by Syme’s mocking tone, Gregory grimly promises him ‘a very entertaining evening’. Syme is made to swear never to reveal what he is about to see and they set off in a hansom cab to an ‘obscure public house’ on the river. To Syme’s astonishment, Gregory orders a splendid supper of lobster and champagne. The dreary pub has further surprises. When they have finished, the stained table begins to revolve, and they descend abruptly through the floor. Below, a low vaulted passageway lined with rifles and revolvers leads to a central chamber which is hung with bombs, like ‘the eggs of iron birds’. Tonight a delegate must be chosen to fill a vacancy on the Central Anarchist Council. Each member of the Council is named after a day of the week; their President is ‘Sunday’. When elected, Gregory’s code name will be ‘Thursday’. The previous Thursday, organizer of ‘the great dynamite coup of Brighton which, under happier circumstances, ought to have killed everybody on the pier’, has perished. Syme tells Gregory he must promise not to reveal his own secret to the anarchists. Gregory, puzzled, agrees. Then Syme tells him that he is a police agent. Gregory snatches up a revolver, but Syme reminds him that, after all, he has sworn not to tell the police that Gregory is an anarchist, and now Gregory cannot tell the anarchists that Syme is a policeman. As they argue, the anarchists file into the chamber . . . This is the start of a story that revels in deception and the putting on and stripping off of masks, where the pursuers become the pursued; a book quite unlike any other in twentieth-century literature and arguably the best of Chesterton’s novels. Together with his Father Brown stories, it has always remained in print. Born in 1874, Chesterton became famous while in his twenties as a wonderfully prolific and endlessly entertaining journalist. His deliberately provocative use of paradox and epigram in those early writings is still fresh and biting. Nobody, faced with the succession of spivs and plutocrats who have lately been smoked from their fur-lined burrows and paraded for our wonderment, could disagree with Father Brown’s comment: ‘To be clever enough to get all that money, one must be stupid enough to want it.’ Chesterton became famous as a latter-day Dr Johnson, his immense physical bulk enshrouded in an enormous black cloak a familiar sight in the Fleet Street pubs. But it is as an imaginative writer that he will be remembered. And he is remembered, although he falls into that odd category of writers who, while read by generation after generation, hardly figure in critical literary histories or university curricula. It comes as a surprise, until one recognizes the justice of it, to encounter the esteem in which foreign masters such as Nabokov and Borges held Stevenson, H. G. Wells, Conan Doyle and Chesterton. The works they admired in particular were those tales whose spirit could perhaps be summed up by an entry in Coleridge’s notebooks: ‘If a man could pass through Paradise in a dream, and have a flower presented to him as a pledge that his soul had really been there, and if he found that flower in his hand when he woke – Aye! and what then?’ Indeed, in Wells’s The Time Machine, the time-traveller returns from the future with a flower of an unknown variety. In Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, an individual soul is divided and inhabits two separate mental and physical worlds. In Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, mundane detail is transformed into the significant clue; the façades of people and houses are opened up to disclose evil or good. And in Chesterton’s writings the characters are not so much interactive social beings as personifications of the state of their souls; personal identity is often a mask for another and opposite being. The only character to maintain his original persona in The Man Who Was Thursday is Sunday, the President of the Central Council of Anarchists. When, by a freakish turn of events, Syme is elected as ‘Thursday’ in Gregory’s place, he finds his new colleagues disquieting: the emaciated, ascetic Monday; the wild-haired and bearded Pole, Tuesday; Wednesday, a French Marquis with the face of a cruel sensualist; Friday, a very old Professor who looks ‘as if some drunken dandies had put their clothes upon a corpse’; and Saturday, a young man in dark glasses that remind Syme of the pennies put on the eyes of the dead. Each, thinks Syme, ‘had something about him . . . which was not normal, and which seemed hardly human’. But most abnormal of all is their leader, the monstrous Sunday, whosevastness did not lie only in the fact that he was abnormally and quite incredibly fat. This man was planned enormously in his original proportions, like a statue carved deliberately as colossal.His head, crowned with white hair . . . looked bigger than a head ought to be. He was enlarged terribly to scale [and] it looked as if the big man was entertaining five children to tea. Sunday charges the anarchists with the task of assassinating the Tsar of Russia and the President of France, who are soon to meet in Paris. We follow them to France, and through a series of terrifying and fantastic adventures in which, one by one, they reveal new, astonishing characters and roles and become the allies of Syme, committed to join him in confronting their mysterious president, Sunday. When they return to London, Sunday greets them with delight and asks, ‘Is the Tsar dead?’

And with that, the monstrous man swings himself ‘like some huge ourang-outang’ over the balustrade of the balcony, lands on the pavement below ‘like a great ball of india-rubber’ and leaps into a passing cab. After a hugely entertaining pursuit, by turns comic and nightmarish, Syme and his new friends finally run him to ground in a large country house. It is evening; the garden is lit with bonfires and torches and there is ‘a vast carnival of people . . . dancing in motley dress’. On the terrace ‘seven great chairs’ have been placed. Each of the six men takes his place and in the centre sits Sunday. The party goes on for hours until, at last, the bonfires die down and people start to wend their way into the house. The climax of the book is as unexpected as the rest. Chesterton’s grip on the reader is playful but firm; this is one of the few books one wants to read at a single sitting. But, in a story charged with Chesterton’s love of paradox, what is to be taken as real? The policemen who become anarchists, or the anarchists who become policemen? Is Sunday God? Or a fat buffoon who loves to play practical jokes? Or, terrifyingly, both? For a relatively short book The Man Who Was Thursday packs in an enormous amount of thrilling action and philosophical speculation, and constantly confounds the reader’s expectations of both. I never went back to my own group of gentle and ineffectual revolutionaries. Middle-aged then, they must be very old or dead by now. The pub was long ago demolished. But I can’t help thinking how good it would have been if just one of their number had been a police agent, if only for the knowledge that someone, somewhere was taking note of them.In return they demand to know who – or what – Sunday is.

‘I? What am I?’ roared the president, and he rose slowly to an incredible height, like some enormous wave about to arch above them and break. ‘You want to know what I am do you? . . . You will understand the sea, and I shall still be a riddle: you shall know what the stars are, and not know what I am. Since the beginning of the world all men have hunted me like a wolf. . . I have given them a good run for their money, and I will now.’

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 39 © William Palmer 2013

About the contributor

William Palmer’s most recent novel, The Devil Is White, has just been published.