For many people in the countryside, life just after the Second World War had not changed so very much from a hundred years before. When I was a young boy in the 1950s our family lived in a small farmhouse in mid-Wales, a couple of miles from the nearest village. We had no mains water or electricity; water came from a well through a hand pump in the kitchen; electricity was provided by a generator – when that burned out one night in November we relied on candles and oil lamps for the whole winter. There was no bathroom, only a tin bath hung on the kitchen door, and an outside privy. Neighbouring farms were much the same, and families scratched a living from the sheep dotted on the surrounding hills. The children spoke Welsh and English and sang Welsh songs on the school bus. Most people went to Chapel on Sunday. It all seemed perfectly normal and likely to last forever.

But the writer Norman Lewis, returning to London in 1946 after three years on active service in North Africa and Italy, wrote that he ‘looked for the familiar in England, but found change . . . it was the search for vanished times that drew me back to Spain’. This is from the foreword to Voices of the Old Sea, the account Lewis wrote of Farol, ‘the least accessible coastal village in north-east Spain’. You will look in vain for Farol on any map: Lewis made the name up. It doesn’t matter: for him the real place had long ceased to exist by the time his book came to be published in 1984.

Like most of his writing, Voices is a warning against corruption – he had already written about the distortion of moral and political life by the Mafia in Sicily and later targets included the destruction of ancient cultures by American evangelical missionaries in South America, and the industrialization of rural India. At first, in 1948, he thought he had found in Farol w

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inFor many people in the countryside, life just after the Second World War had not changed so very much from a hundred years before. When I was a young boy in the 1950s our family lived in a small farmhouse in mid-Wales, a couple of miles from the nearest village. We had no mains water or electricity; water came from a well through a hand pump in the kitchen; electricity was provided by a generator – when that burned out one night in November we relied on candles and oil lamps for the whole winter. There was no bathroom, only a tin bath hung on the kitchen door, and an outside privy. Neighbouring farms were much the same, and families scratched a living from the sheep dotted on the surrounding hills. The children spoke Welsh and English and sang Welsh songs on the school bus. Most people went to Chapel on Sunday. It all seemed perfectly normal and likely to last forever.

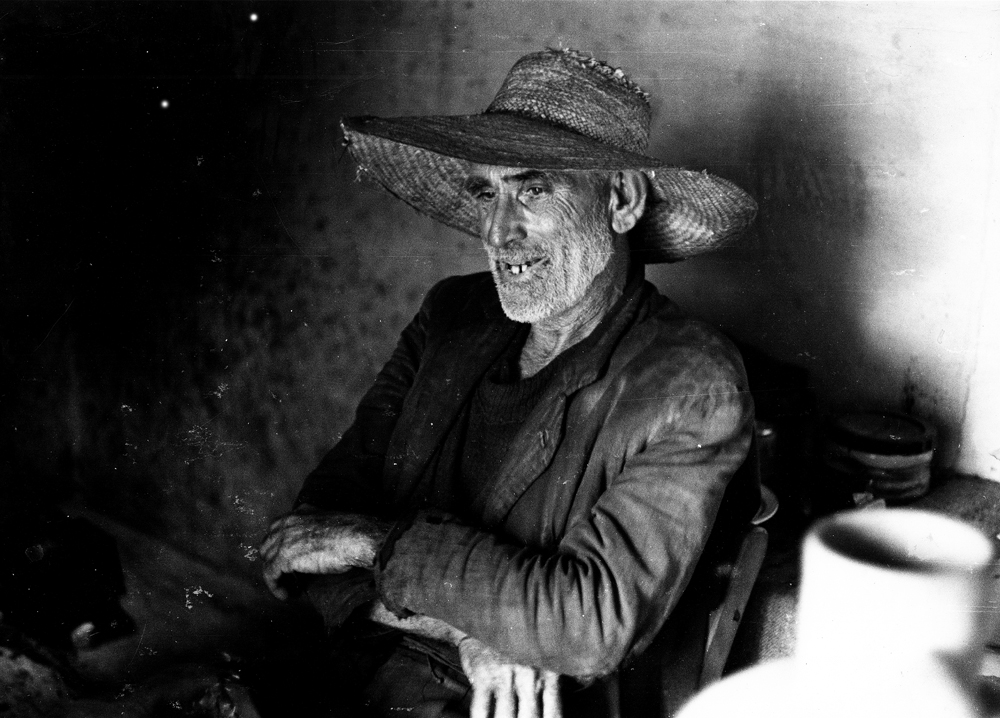

But the writer Norman Lewis, returning to London in 1946 after three years on active service in North Africa and Italy, wrote that he ‘looked for the familiar in England, but found change . . . it was the search for vanished times that drew me back to Spain’. This is from the foreword to Voices of the Old Sea, the account Lewis wrote of Farol, ‘the least accessible coastal village in north-east Spain’. You will look in vain for Farol on any map: Lewis made the name up. It doesn’t matter: for him the real place had long ceased to exist by the time his book came to be published in 1984. Like most of his writing, Voices is a warning against corruption – he had already written about the distortion of moral and political life by the Mafia in Sicily and later targets included the destruction of ancient cultures by American evangelical missionaries in South America, and the industrialization of rural India. At first, in 1948, he thought he had found in Farol what he had always searched for: an untouched and ancient society. When Lewis arrived he lodged in the village inn, ‘generally agreed to be the worst in Spain’. He was driven out by the smell of cats. The village was overrun with them, ‘an ugly breed, skinny with long legs, and small pointed heads. You saw little of them in the daytime, but after dark they were everywhere.’ He moved quarters to lodge with a formidable woman known to everyone as Grandmother. ‘Large, dignified and slow-moving’, she dominated the lives of the women of Farol, prescribing herbal remedies, providing advice on birth control (condoms were illegally supplied by the local clairvoyant), giving permission for when it was proper for a couple to have a child, and even naming their children. The names were taken from a book on great generals, so the village was full of ‘inoffensive little boys called Julio César, Carlo Magna and Napoleon’. Her daughter and son-in-law, Sebastian, lived with Grandmother in a state of some friction over Sebastian’s seeming unwillingness, or inability, to produce a grandchild. Farol had fifty houses, a small, decayed church, a ship’s chandler’s, a butcher’s shop and a general store selling a wide range of goods ‘from moustache wax to hard black chocolate that had to be broken up with a hammer’. There was also a bar, used by the local fishermen and called The Mermaid for its display of ‘the mummified corpse of a dugong’ hanging from the ceiling. The fishermen gathered under the ‘mermaid’ every evening. Their usual language was Catalan, but to tell tales of their days at sea they used classic Castilian in a form of rhythmic verse that was an extraordinary mixture of the everyday and the Homeric. If a stranger entered and took too much notice, they reverted to gossip in the local Catalan dialect. Lewis was schooled by Sebastian to make himself modestly retiring in the bar, so that the often very beautiful incantations could continue, and he finally felt accepted by Farol when he heard his own name pop up only half satirically in a fishing yarn. The local church was neglected, as custom prevented any male from attending Mass, and the unmanly piety of the nearby village of Sort was ridiculed. Fortunately, Farol’s priest Don Ignacio, whose main interest was in digging up whatever small artefacts he could find in nearby Roman ruins, was an easy-going, lovable and comic figure, as was his friend, Don Alberto, the aristocratic, quixotic local landowner. The two men had much in common:Don Ignacio’s house was bare and claustrophobic as Don Alberto’s, and he lived uncomfortably attended by an old woman virtually interchangeable from the one who looked after the old landowner . . . This grey-haired slatternly old creature was generally accepted – as in the case of Don Alberto’s housekeeper – to have been his mistress . . .This, in an irreligious village, gave a little prestige to the genial priest. And his friend Don Alberto was a charitable and generous landlord to his tenants, though not a rich man by any means. The two were the only educated men for miles around, scholars who loved to discuss local customs and traditions, to regret the passing of some and to laud the staying power of others. All in all, for them, and for Lewis, the two villages, Farol and Sort, had remained unchanged in their customs and essentials of life for centuries, partly because of their physical isolation at the end of a precipitous dirt road that was often impassable in winter. It is easy to sympathize with Lewis’s respect for the tough, independent, bloody-minded fishermen and the eccentricities of the impoverished landowner and priest. He became a fisherman himself in partnership with his friend Sebastian, and the lovingly detailed descriptions of diving and fishing in crystal waters are superb. The two men maintained a safe distance from the professionals, diving only for those fish that the Farol men ignored. But any illusion that the people in these isolated villages lived an idyllic life, playing guitars and feasting on Elizabeth David dishes, is dispelled by this book. The guitar was despised, the meals were mostly stews of poor meat, and the wine was thin and acidic. Between October and March, hunkering down for the long winter, the fishermen had to live on the proceeds from their summer catch. Lewis may have made great efforts to fit in and he certainly helped many of the hopelessly innumerate locals order their affairs and avoid being cheated by the French dealers who came down to buy their fish, but he doesn’t seem to have hung around much when summer ended. Perhaps his unsullied vision could have lasted a little longer, but change came suddenly. Disaster and rescue, of a sort, arrived in three forms: a great storm, a virus and Jaime Muga. A poor fishing season was succeeded by an October storm that left three of the five largest fishing boats smashed to pieces on the beach. The neighbours and rivals in Sort were also suffering. The forest of evergreen oaks from which cork was traditionally harvested was greying and dying, infested by a virus. The long-term existence of the two villages was in doubt as the young began to move away to look for work in the cities. And Muga? He was a local black marketeer who set out to save Farol and Sort from themselves – and for himself. Lewis noticed the first changes when he returned for his second summer. The local inn bore a new sign: ‘Guests admitted. Salubrious accommodation, and meals served at all hours.’ Builders had ripped out the labyrinth of odd-shaped rooms and replaced them with fourteen bedrooms. ‘Three bathrooms were incorporated, an exotic extravagance in local eyes.’ The first guests arrived at the end of May, ‘providing instant and final confirmation that all outsiders were basically irrational, when not actually mad’. Muga’s grip on the village rapidly grew stronger. He persuaded the younger fishermen to provide boat trips for the tourists and he cleaned up the waterfront. Three more hotels were quickly built. The general shop now sold tourist trash, and a new café served frozen hake brought up from Barcelona. By the time Lewis came back for his third and last season, the old bar had been redecorated, the ‘mermaid’ had disappeared and the poetry had gone, replaced by ersatz flamenco music. His friend Sebastian had abandoned fishing; Lewis found him working, rather shamefaced, behind the desk at one of the hotels. There were many tourists now and some of the better-looking young fishermen earned handsome tips by sleeping with women tourists. The cats had been hunted down and killed. In three years, the ancient life of Farol had been destroyed and replaced by a tourist economy, while Sort had become a ghost town. A few things had not changed: Lewis called on the priest Don Ignacio who, as usual, was entertaining his good friend Don Alberto. Talking of one of the few remaining fishermen who continued to hold to the belief that the tourists would depart and the good old days return, Don Ignacio said, ‘Sometimes it is necessary to believe things that are absurd. When an illusion dies, a hope is born. He has as much right to his hope as we to our resignation.’ But Muga won. Welcome to the Costa Brava. And our old cottage in Wales? We moved away in the ’60s. A little while ago I found it on the Internet advertised as a ‘self-catering holiday facility’, with all mod cons.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 74 © William Palmer 2022

About the contributor

William Palmer’s study of the place of alcohol in the lives and work of writers, In Love with Hell, was published in 2021 by Little, Brown. You can also hear him on our podcast, Episode 38, ‘Literary Drinking’.