- Magazine The Quarterly

Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly

Each issue of Slightly Foxed offers 96 pages of lively personal recommendations for books of lasting interest – books, including fiction and non-fiction, that have stood the test of time and have left their mark on the people who write about them.

View the Spring 2024 issueCurrent Issue & Back Issues

- Books Books

Slightly Foxed Books

Slightly Foxed brings back forgotten voices through its Slightly Foxed and Plain Foxed Editions, a series of beautifully produced little pocket hardback reissues of classic memoirs, all of them absorbing and highly individual. For younger bookworms – and nostalgic older ones too – there’s the Slightly Foxed Cubs series, in which we’ve reissued a number of classic nature and historical novels. Our online bookshop also includes a carefully-curated selection of titles from other publishers’ lists.

View BooksBrowse Slightly Foxed Books

Browse All Books

Delectable, collectable hardback books | Made in England

- Goods Goods & Gifts

Goods

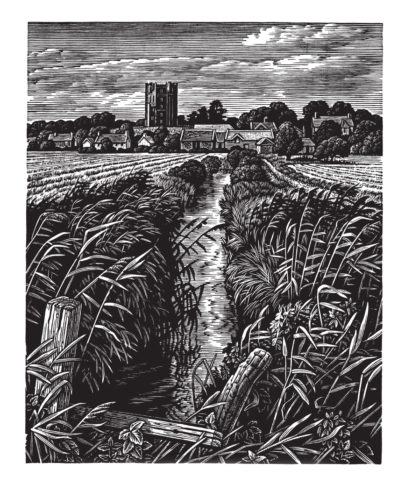

Whether you’re in search of a present for a bookish friend or relative, or a treat for yourself, Slightly Foxed offers a range of book-related merchandise, including cloth-bound notebooks, sturdy and good-looking book bags, beautifully crafted bookcases, shelves and bookends, handy bookplates featuring a specially-commissioned woodcut and a number of illustrated bookmarks, postcards and seasonal greetings cards.

View GoodsBrowse Goods & Vouchers

Gifts

Almost everything listed on our website can be sent to you, or directly to a gift recipient together with a hand-written gift card. The office is well-stocked with smart gift cards, reams of brown wrapping paper and foxed ribbon. For last-minute gifts, we can send an e-gift card in advance of sending the subscription or item. You can arrange to do this during the checkout process.

- Etc Et cetera

Welcome

Welcome to our virtual kitchen table. Here you can read articles and extracts from the quarterly magazine and our books, catch up with newsletters, find out more about our writers and artists, use the online index to hunt down articles published in back issues and seek out books featured in the magazine, listen to episodes of our podcast, and much more besides.

Dive inHighlights

- Podcast Episode 49: Down to Earth: A Farming Revival

- Press & Reviews

- Bookshop of the Quarter: Spring 2024

- SF Edition No. 66, My Salinger Year | New from the Slightly Foxed Bookshelves

- ‘Sauntered homeward by unfrequented ways . . . ’ | A Countryman’s Spring Notebook

- Supper with the sun in our eyes | A Countryman’s Summer Notebook

- Michael Holroyd | Basil Street Blues Extract

Favourites

You can listen to every episode of the Slightly Foxed podcast in full for free

Click here to browse the podcast archive

Click here to browse the podcast archive