In 1969, a friend and I rather rashly accepted a commission to produce from scratch a new set of guides to Britain’s inland waterway network. We were young, naïve, confident and in need of the money. Four years and 2,000 waterway miles later, the project was finished and the four books quickly became the standard waterway guides, still in print over forty years later.

It was an enjoyable, if frenetic, adventure and I gained a detailed knowledge of the history of canals and river navigation, and their place in the landscape, along with a thorough, if rather linear, vision of urban and rural Britain. I also developed an enduring passion for canals and canal life which, at its most intense point, drove me to buy my own canal boat.

Reading about other people’s canal adventures was an essential part of the learning process. There are a number of classic waterway books. Top of everyone’s list is Narrow Boat by L. C. T. Rolt. First published in 1944, and in print ever since, this is the perfect introduction to the rather secret world of canals and waterways. But it was by chance that I came across Emma Smith’s Maidens’ Trip (1948), complete with John Mintonesque dust-wrapper, in a second-hand bookshop in the early 1970s.

During the Second World War women, who from 1943 became subject to the demands of National Service regulations, were often put to work in rather unexpected areas of activity. Much of this has been well documented. However, one of the lesser known fields of female employment was canal boating, a reflection of the wartime importance of this method of transport for the movement of essential but not urgent cargoes such as coal, food, spare parts and raw materials. A number of women, generally young, fit and adventurous, responded to advertisements placed by the Ministry of War Transport’s Women’s Training Scheme. Most had little or no boating experience but, after some rather basic and brief training, they were

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIn 1969, a friend and I rather rashly accepted a commission to produce from scratch a new set of guides to Britain’s inland waterway network. We were young, naïve, confident and in need of the money. Four years and 2,000 waterway miles later, the project was finished and the four books quickly became the standard waterway guides, still in print over forty years later.

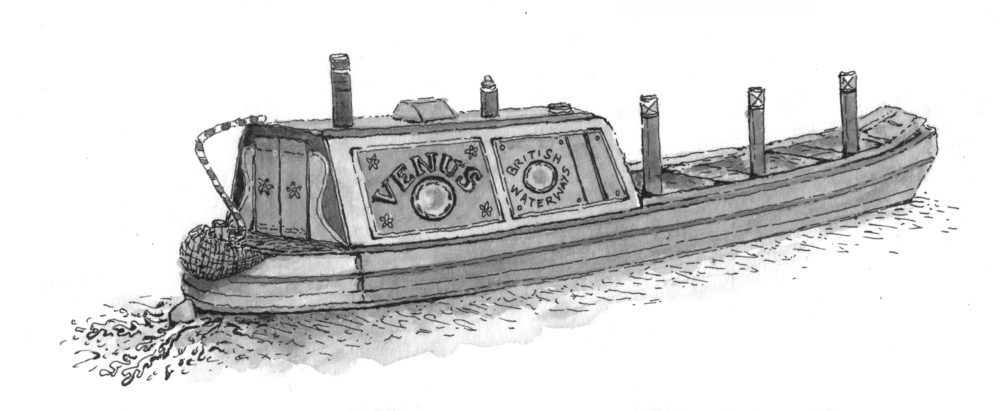

It was an enjoyable, if frenetic, adventure and I gained a detailed knowledge of the history of canals and river navigation, and their place in the landscape, along with a thorough, if rather linear, vision of urban and rural Britain. I also developed an enduring passion for canals and canal life which, at its most intense point, drove me to buy my own canal boat. Reading about other people’s canal adventures was an essential part of the learning process. There are a number of classic waterway books. Top of everyone’s list is Narrow Boat by L. C. T. Rolt. First published in 1944, and in print ever since, this is the perfect introduction to the rather secret world of canals and waterways. But it was by chance that I came across Emma Smith’s Maidens’ Trip (1948), complete with John Mintonesque dust-wrapper, in a second-hand bookshop in the early 1970s. During the Second World War women, who from 1943 became subject to the demands of National Service regulations, were often put to work in rather unexpected areas of activity. Much of this has been well documented. However, one of the lesser known fields of female employment was canal boating, a reflection of the wartime importance of this method of transport for the movement of essential but not urgent cargoes such as coal, food, spare parts and raw materials. A number of women, generally young, fit and adventurous, responded to advertisements placed by the Ministry of War Transport’s Women’s Training Scheme. Most had little or no boating experience but, after some rather basic and brief training, they were assembled into teams of three and sent off in charge of a pair of narrow boats. Such pairs, one equipped with a motor towing another without an engine and known as a butty, were the long-established backbone of canal transport. Each was equipped with a small cabin, with two of the crew living in the slightly larger motor-boat, and the third alone in the butty. The canal world was then a secret one, with its own rituals and attitudes, and famous for close family values and traditional working methods. Like many civilians employed on war service the women were given badges to explain their lack of uniform. Those worn by canal boatwomen carried the initials IW, for Inland Waterways, but in the hidden and mysterious world in which they operated the IW came quickly to stand for Idle Women. One of those who answered the call was Emma Smith. Born Elspeth Hallsmith in Newquay in 1923, she had a challenging childhood, redeemed by a close relationship with her siblings and the eternal presence of the sea. She left school at 16, moved to London and found a job in the Records Section of the War Office. Desperate to escape the boredom of this life she volunteered in 1943 to become a trainee boatwoman, based on the Grand Union Canal in west London. Maidens’ Trip is an account of her first canal trip, taking steel bars from London to Birmingham, and then bringing coal from Coventry back. The opening lines set the scene:Emma is teamed up with Charity and Nanette, three girls who in ordinary life would probably have had little in common. They are set to work on Venus, their motor-boat, and Ariadne, their butty. Despite their differences, they have to learn very quickly to work together and, more important, to live together in the cramped, damp, cold, crowded and muddled world of the canal-boat cabin, a small space the management of which demands a well-developed sense of order and tidiness. As young girls in their late teens, they mostly lacked this fundamental necessity, and so lived for weeks in chaos and even squalor. And as canal boatwomen there was no respite, no escape from the claustrophobic world in which they found themselves. What they faced was relentless hard work, hasty and often ill-prepared food eaten on the run, extremes of exhaustion and the constant challenges posed by boats, locks, bridges, tunnels and the unpredictable behaviour of the professional boat families encountered along the way. Their trip, described by Emma in the third person, is a sequence of excitements, adventures and disasters. It is also an insight into the minds of three young women randomly thrown together, and forced to cope, not only with their alien world, but also with each other. Of course they do cope, and are driven onwards by the need to complete the trip, to deliver the goods, and to survive every challenge thrown at them along the way. They fall into the canal, hurt themselves in various unpleasant ways, fall in and out with boating families, and with each other, suffer mechanical breakdowns, boating crises, including a near sinking, and lock mishaps. The weather too is often appalling.It must have been an astonishing imposition for the canal people when war brought them dainty young girls to help them mind their business, clean young eager creatures with voices so pitched as to be almost impossible to understand . . . For years, for generations, they had worked out their hard lives undisturbed, almost unnoticed. Then suddenly – the war: and with it descended on them these flighty young savages, crying out for windlasses, decked up in all manner of extraordinary clothes that were meant to indicate the marriage of hard work with romance.

At one point Charity is nearly killed when she hits her head against an unseen bridge, and has to go home. Emma and Nanette struggle on and, finding they can’t manage, enlist the help of Wilfred, a much older male friend with nautical experience. In the process, and unwittingly, they break the strict moral code of the canal world.We awoke to the racketing of a gale, and by gale our day was distinguished. There were no hills to break its fury. The wind tore straight across flat fields and caught us broadside on. The boats, poor empty shells, staggered against the bank and there were pinned as helpless as butterflies on a board. Again and again we shafted them out and whipped the engine up to its full speed. Again and yet again they disobeyed us and obeyed the cruder strength that bore down on them across the thorny hedges.

Emma and Nanette only escape opprobrium by putting it about via the efficient gossip network of the canal world that Wilfred is an uncle.There are none who embrace orthodoxy with greater ardour than the canal boaters . . . And their morals, they could proudly add, are above reproach, are narrow almost to the exclusion of breathing. If a young man takes a girl to the pictures, he is courting her, and no other girl from that moment may be treated to more than a ‘how d’you do’ and a nod. If a woman talks to someone else’s husband, and the wife not by, she runs the risk of serious calumny.

Inevitably, they encounter young canal boatmen, and entertain various fantasies about the life such a union would represent. Nanette courts, very briefly and mostly in her head, a comely young boatman called Eli, but when he asks her to the cinema a second time, she sees the trap and escapes by taking Emma and Charity along. After the cinema they go for fish and chips, and try in vain to draw Eli into their world but soon realize the gulf is unbridgeable. In the end, it is the appeal of a return to their own world that drives them onwards.News on the cut travels with lightning speed . . . No accident can be kept a secret; no encounter is private; no conversation unrepeated. Courting can never be clandestine, and behaviour is hung out like a flag for all to see. A spotlight illuminates the life of a boating girl or boy from birth in a cabin to the grave . . .

And this is how Elspeth Hallsmith spent the rest of the war. In September 1946 she went off to India with a team of documentary film-makers that included Laurie Lee and during the next nine months she, and others, encouraged him to write Cider with Rosie. Back in England in 1947, Elspeth turned herself into Emma Smith and wrote Maidens’ Trip. It was published the following year and won the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize. Emma’s next book, The Far Cry (1949), a novel about a family in India, was an even greater success, winning the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. But that was the end. Married in 1951, and widowed not long after, Emma moved to rural Radnorshire to bring up her two children. Many years passed before she wrote anything again. Long out of print, Maidens’ Trip and The Far Cry were forgotten until the novelist Susan Hill found a copy of the latter in a jumble sale and encouraged its reissue by Persephone Books, where it joined a list of forgotten classics by women writers. Having lived long enough to enjoy the process of rediscovery, Emma Smith wrote her final book, The Great Western Beach, a memoir of her childhood in Cornwall, which was published in 2008. My rediscovery of Emma Smith had taken place about thirty years before Susan Hill’s. But I had done nothing about it, other than greatly enjoy her description of a world about which I knew quite a bit. This knowledge probably blunted my vision to the extent that I did not really appreciate what I was reading. I also knew that Emma was not alone in writing about that extraordinary wartime chapter in waterway history, for adjacent on my shelf is a copy of Susan Woolfitt’s Idle Women (1947). Mrs Woolfitt’s book, covering a similar experience in a broadly similar way, but from the point of view of a much older, married woman, is of great interest to a canal enthusiast like myself but lacks those vigorous, poetic and comic qualities that make Maidens’ Trip so exceptional. The fact is that Emma Smith wrote a book whose appeal should be universal, and far beyond the narrow limits of the waterway world.The web of London, with its million cries and movements, took us back. On the whole we were glad. Deserts turn lonely after a time, and cows as companions seem inadequate. Besides, we knew that after plunging into the hurly-burly for a few days we should then withdraw again into our deserts and find them twice as agreeable for the change. The slowness of cows, lately an irritation, would then seem philosophic.We needed our contrasts and were given them, lucky and undeserving creatures that we were, as regular as clockwork.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 46 © Paul Atterbury 2015

About the contributor

When not appearing on the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow, Paul Atterbury lives by the sea in Weymouth and writes books. Subjects range from pottery and silver to the First World War, but railways and canals remain perennial favourites.