For me, some books act like a time machine, leading me back into my past, reminding me of how it felt to be young. This doesn’t happen often, but when it does, the effect is intense. Sensations that I had forgotten arise afresh, and the world seems new again.

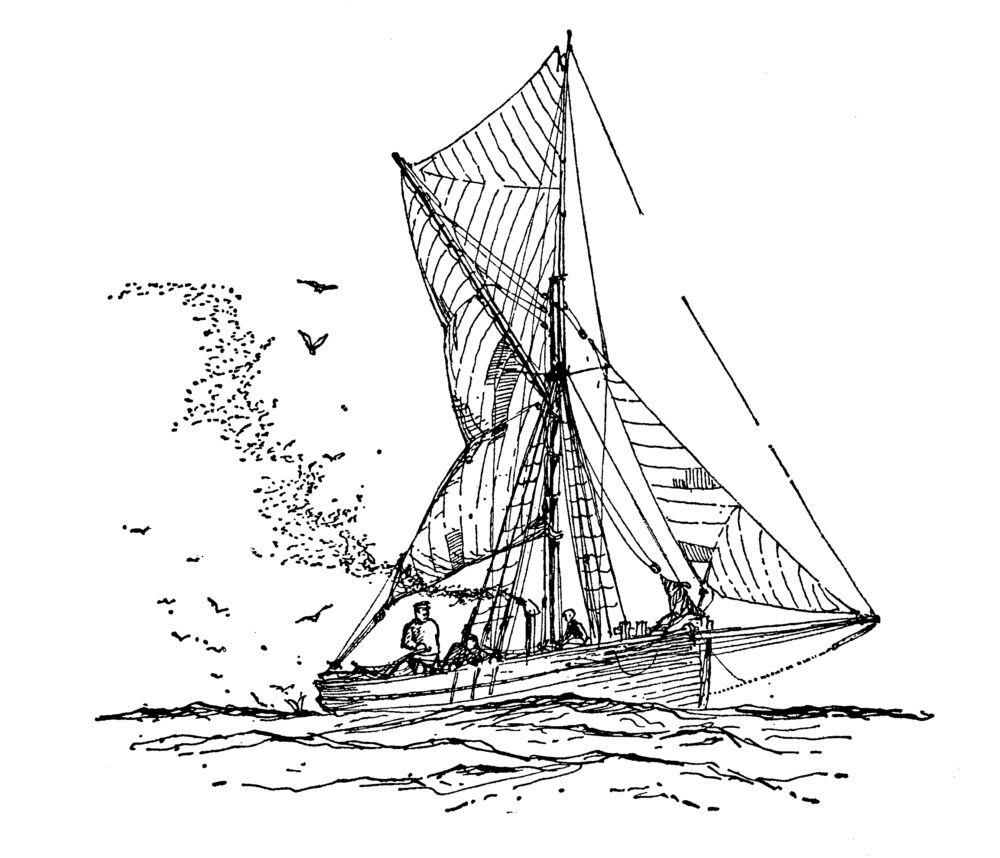

Hugh Falkus’s The Stolen Years (1965) is one of those books, evoking for me the simplicity and innocence of boyhood. Not that his upbringing was anything like mine: far from it. He was a child of the inter-war period, inhabiting first a converted Thames barge on the Essex coast, and later an old sixty-ton, straight-stemmed cutter, moored in a Devon estuary; I grew up in the 1960s and 1970s, in a house in West London. Nevertheless, his reminiscences stir my own.

Falkus’s childhood was spent among mudflats, reed-beds and shorelines. He caught his first fish at the age of 4, learned to shoot when he was 6, and became an expert helmsman while still in short trousers. He passed many contented hours afloat, messing about in boats, sometimes with an adult, sometimes alone. Most of these boats had rotting boards, unreliable engines or ancient sails, liable to tear in a strong wind; heading out to sea in one of these was always a risk. What is especially striking to the modern reader is the freedom the young Falkus was allowed to roam unaccompanied, on land or water. No fuss then about handing a shotgun to a boy and letting him venture out on the marshes before dawn in pursuit of wildfowl. The Stolen Years is a memoir of this happy time. There is no continuous narrative; each chapter forms a separate episode, and by the end of the book the small boy met at the outset has become a young man. An early chapter extols the qualities of Sally, in the same class as Hugh at infant school, who for a modest consideration would lift her skirts and ‘show you my bum’; the penultimate chapter is an elegy to a dark, slim girl in a green dress, glimpsed standing in the lamplight in the do

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inFor me, some books act like a time machine, leading me back into my past, reminding me of how it felt to be young. This doesn’t happen often, but when it does, the effect is intense. Sensations that I had forgotten arise afresh, and the world seems new again.

Hugh Falkus’s The Stolen Years (1965) is one of those books, evoking for me the simplicity and innocence of boyhood. Not that his upbringing was anything like mine: far from it. He was a child of the inter-war period, inhabiting first a converted Thames barge on the Essex coast, and later an old sixty-ton, straight-stemmed cutter, moored in a Devon estuary; I grew up in the 1960s and 1970s, in a house in West London. Nevertheless, his reminiscences stir my own.

Falkus’s childhood was spent among mudflats, reed-beds and shorelines. He caught his first fish at the age of 4, learned to shoot when he was 6, and became an expert helmsman while still in short trousers. He passed many contented hours afloat, messing about in boats, sometimes with an adult, sometimes alone. Most of these boats had rotting boards, unreliable engines or ancient sails, liable to tear in a strong wind; heading out to sea in one of these was always a risk. What is especially striking to the modern reader is the freedom the young Falkus was allowed to roam unaccompanied, on land or water. No fuss then about handing a shotgun to a boy and letting him venture out on the marshes before dawn in pursuit of wildfowl. The Stolen Years is a memoir of this happy time. There is no continuous narrative; each chapter forms a separate episode, and by the end of the book the small boy met at the outset has become a young man. An early chapter extols the qualities of Sally, in the same class as Hugh at infant school, who for a modest consideration would lift her skirts and ‘show you my bum’; the penultimate chapter is an elegy to a dark, slim girl in a green dress, glimpsed standing in the lamplight in the doorway of a Devon farmhouse, never to be seen again. These two chapters are the exception, however; otherwise women scarcely feature in the book. Neither does school; most of the action takes place outside, in or around water. Incidents that might seem inconsequential to an adult are related with a child-like zeal that imbues them with emotional significance. Thus we are told of an epic struggle with a giant eel, dragged to the surface, that thrashes its monstrous tail before plunging back into the depths, leaving a line broken and a rod smashed; of a huge lobster, speared in a rock-pool, and triumph turning to despair when the captive crustacean, after feigning lifelessness, stealthily escapes back into its element. One of the most dramatic chapters describes sailing single-handed into a gale as the sea whips up into a fury and the light fades, the old yacht plunging into the blackness, taking on water as its worn-out seams gape under the strain. Falkus manages to navigate a foaming reef and reach the shelter of the estuary, but his boat is sinking beneath him. Eventually he beaches her and falls asleep in the bows, exhausted. Soon after sunrise he wakes, cold and stiff, the taste of salt on his lips, and jumps down on to firm sand, his legs rubbery. Sadly he contemplates his beloved old boat, knowing that she will never sail again. These stories are told in lucid, muscular prose. In Falkus’s vivid descriptions one can smell the tang of the sea, feel the cold wind against the skin and the cling of wet clothes in driving rain, hear the crunch of boots on frozen ground. Through the clear gaze of a child we also meet old eccentrics such as Puggy Dimmond, a one-eyed old man with a long, bent nose who lives alone aboard an ancient fishing smack, retired to the mud of an Essex estuary. There is comedy as well as drama in these anecdotes, much of it deriving from the mistaken optimism of Falkus’s sweet-natured father. One relates an evening sail across the Channel to Holland, aboard a converted ship’s lifeboat. Tacking against a headwind for hour after hour, they lose their way in thickening fog and decide to anchor until morning. When the day dawns and the mist clears, they find themselves back where they had started. The book opens with a character sketch of Falkus’s father:It is true that my father had other interests besides fishing. Boats and budgerigars, for instance, and occasionally the world of commerce. But fishing was the thread which bound his life together and he fished, as he lived, with infectious and inexhaustible enthusiasm. A great big broad fellow, with a merry mouth and an astonishing constitution, he lived to the fullness of eighty-five, and to say that there were not many like him is no sentimental exaggeration. There have been men who fished longer; many who fished more skilfully; but few, I fancy, who fished harder . . . During the contemplation of a fishing trip his naturally sanguine temperament reached a state of sustained euphoria bordering on the beatific. Lunatic, my mother called it.The final chapter tells of a wild December night when Falkus’s father, who had been fishing that afternoon from a dinghy on a reef where the tide ran fast, fails to come home. Seized with apprehension, Falkus runs down to the shore. The wind is blowing in great gusts, with flurries of snow; the weed-covered rocks are wet and slimy. Peering into the blackness, he makes out something rolling in a ridge of foam – his father’s dinghy, still anchored but capsized. The man himself is nowhere to be seen. By this time, Falkus calculates, six hours must have passed since he went overboard. Frantically he tries to imagine what his father might have done: by kicking off his boots and outer clothes, he might have been able to stay afloat for a while. The current would have carried him towards the Susannah, an old fishing smack moored three-quarters of a mile away, just off the main channel. It is just possible that he found it in the failing light and managed to climb aboard. Flashing his torch, Falkus runs panting towards a small cluster of rowing boats drawn up on the sand. Miraculously he finds one still equipped with rowlocks and oars – though not a pair. He pushes off into the night, and with the strength of desperation rows across the choppy water, trying to guess where Susannah lies. Then he hears a voice crying out; and immediately afterwards, a shadowy hull looms out of the darkness. Falkus swings the rowing boat into the lee of the smack, grasps the gunwale and peers over the side. There is his father, crouching in the cockpit, clad only in his underwear. ‘Oh Hugh,’ he says, ‘I am glad to see you.’ The adult Falkus was a handsome, virile man, with a commanding presence. After leaving school he learned to fly and enrolled in the RAF. In the summer of 1940, his Spitfire was shot down over France after he had downed three enemy bombers; underneath his flying suit he was still wearing his pyjamas. The Germans took him for a spy and sentenced him to death. In a gesture of contempt he turned his back on the firing squad to watch trout rising in a river outside the fence – before receiving a miraculous, last-minute reprieve. As a prisoner-of-war, he spent years tunnelling in a series of frustrated attempts to escape, until he eventually succeeded, reaching England only ten days before the German surrender. After the war Falkus became known as a broadcaster on natural history and made a series of award-winning films. It was while he was shooting one of these, about basking sharks, that his boat was caught in a sudden squall off the west coast of Ireland and sank. Falkus took charge and, as the strongest swimmer, struck out for the shore, leaving his wife and the three members of the film crew clinging to floating debris. After a long struggle he made landfall and raised the alarm, but by the time help arrived, the others had perished. In the final paragraphs of The Stolen Years Falkus reflects on his father, and on a life well lived.

I like to think that he found his lonely creek – and lies always by the sea-lavender-covered marshlands, where there is no sound but the distant sea and the curlews crying. In later years, my own narrow escapes and a world crashed into ruin put me beyond wonder at the mystery of life on this spinning planet. We cling by our fingernails to the rim of a great wheel, and some of us give up and slip off, and some cling for a time, and some stick. Although sooner or later all visions fade; the most tenacious grip loosens. What do men do with stolen time? Everyone lives in the tight little house of his mind, each with its own façade, and no one really knows what goes on in the next house. But sometimes, when the wind raved in the chimney, we would sit together snug beside a fire in some smoke-darkened tap-room and drink a pint to the stolen years.Falkus wrote several other books, among them one revered as the bible of sea-trout fishing, yet he considered The Stolen Years his best. Some years after his death a ‘warts-and-all’ biography by Chris Newton, Hugh Falkus: A Life on the Edge, revealed an unpleasant side to his character. In later life, it seems, Falkus became an irascible bully and a sexual predator. It is perhaps better not to know too much about one’s heroes. Yet nothing can spoil the pleasure I find in rereading The Stolen Years. I have only to dip into Falkus’s memoir of his boyhood and I am 11 years old again, my hand poised over a split-cane fishing rod or gripping an oak tiller.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 71 © Adam Sisman 2021

About the contributor

Adam Sisman is a writer, specializing in biography. His most recent book is The Professor and the Parson: A Story of Desire, Deceit and Defrocking (2019).