In July 1967 the schoolmaster and part-time novelist J. L. Carr took two years’ leave of absence to see if he could make a living as a publisher of illustrated maps and booklets of poetry. Both were unusual: the maps featured small, annotated drawings of people, buildings, flowers, animals and recipes associated with places in the old English counties and were meant for framing and to stimulate discussion, while the works of British poets were presented in 16-page booklets, as Carr believed that people could only absorb a few poems at a time.

Carr designed the maps himself and wrote on his first map of Northamptonshire (1965): ‘Travellers are warned that the use of this map for navigation will be disastrous.’ The maps sold initially for £1 each and the booklets for 6d to adults or 4d to children, until he received orders from children with suspiciously mature handwriting. By the end of 1968 his savings had dwindled to £400, but with six months left of his official leave he turned the corner into profitability. The Quince Tree Press, so called because there was a quince tree in his front garden, operated from old shoe boxes (into which his little books fitted neatly) stored on shelves in a bedroom of his modest house in suburban Kettering.

The income from his maps and books of poetry allowed Carr the freedom to give up teaching for good and also to write the novels for which he is most highly regarded: A Month in the Country (see SF No. 8) won the Guardian Fiction Prize in 1980 and was short-listed for the Booker Prize, as was his next novel, The Battle of Pollocks Crossing (1985). This was a remarkable achievement for a former schoolteacher who didn’t publish his first novel until he was 52. But then, he was a remarkable man. He wrote 8 novels, all in different styles; designed nearly 100 maps; compiled 6 small d

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIn July 1967 the schoolmaster and part-time novelist J. L. Carr took two years’ leave of absence to see if he could make a living as a publisher of illustrated maps and booklets of poetry. Both were unusual: the maps featured small, annotated drawings of people, buildings, flowers, animals and recipes associated with places in the old English counties and were meant for framing and to stimulate discussion, while the works of British poets were presented in 16-page booklets, as Carr believed that people could only absorb a few poems at a time.

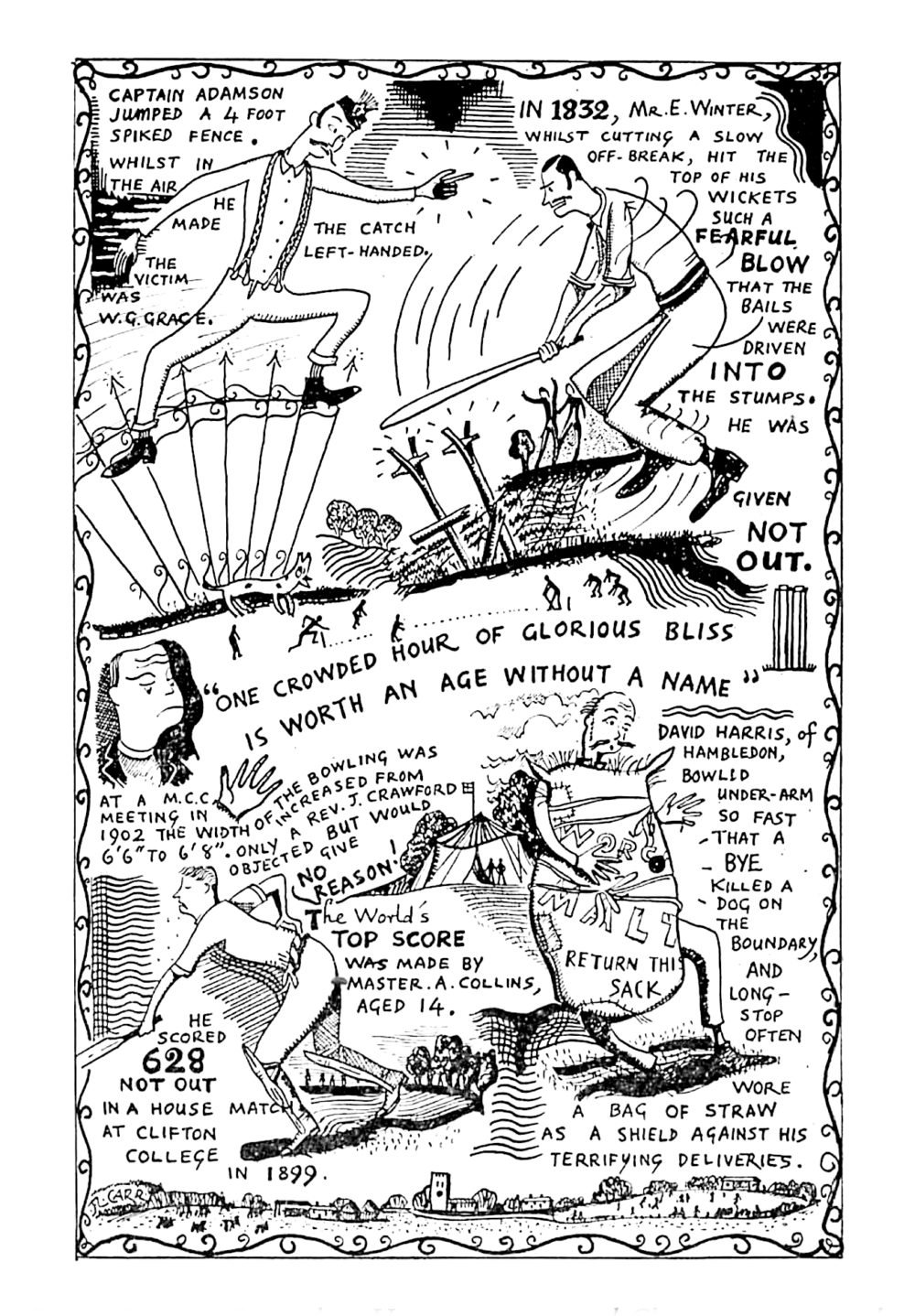

Carr designed the maps himself and wrote on his first map of Northamptonshire (1965): ‘Travellers are warned that the use of this map for navigation will be disastrous.’ The maps sold initially for £1 each and the booklets for 6d to adults or 4d to children, until he received orders from children with suspiciously mature handwriting. By the end of 1968 his savings had dwindled to £400, but with six months left of his official leave he turned the corner into profitability. The Quince Tree Press, so called because there was a quince tree in his front garden, operated from old shoe boxes (into which his little books fitted neatly) stored on shelves in a bedroom of his modest house in suburban Kettering. The income from his maps and books of poetry allowed Carr the freedom to give up teaching for good and also to write the novels for which he is most highly regarded: A Month in the Country (see SF No. 8) won the Guardian Fiction Prize in 1980 and was short-listed for the Booker Prize, as was his next novel, The Battle of Pollocks Crossing (1985). This was a remarkable achievement for a former schoolteacher who didn’t publish his first novel until he was 52. But then, he was a remarkable man. He wrote 8 novels, all in different styles; designed nearly 100 maps; compiled 6 small dictionaries; published about 50 small books of other people’s poetry and 19 booklets of artists’ woodcuts; wrote a social history of the early settlers of South Dakota and 8 children’s English language books; sculpted stone gargoyles for his local church; and created a huge record in watercolours of the interiors and exteriors of buildings in Northamptonshire, his adopted county. His extraordinary life is described in an excellent biography, The Last Englishman, by Byron Rogers. In 1977 Carr published the first of his pocket dictionaries, the Dictionary of Extra-ordinary English Cricketers. It was an almost instant success and led to several other biographical dictionaries with quirky and often improbable entries. But what gave him the idea? Joseph Lloyd Carr was born in May 1912 in a railway cottage at Thirsk Junction in Yorkshire where his father was night stationmaster. His given names caused him grief: he replaced the first with Jim or even James, so his family called him Lloyd, a name for which he was teased at school. In the note he sent with a copy of his map of Wales to the National Library in Cardiff he wrote: ‘Presented . . . by James Lloyd Carr, a Welsh patriot by proxy, who alone and without allies defended the land of his fathers (by baptism) on many a bloody-nosed Yorkshire playground while scarcely knowing that Wales existed.’ Carr knew academic failure twice. He failed his Eleven Plus but was sent as a paying pupil to Castleford Secondary School – something his parents could ill-afford. Then he failed to get into teacher-training college because, allegedly, when asked why he wanted to be a teacher he replied, ‘It gives so much time for other pursuits’ – a glib remark that he regretted when he was forced to take a job as a lowly teaching assistant. The next year he gained admission to a teacher-training college in Dudley and became a supply teacher in Birmingham. Five years later, in 1938, Carr applied for an exchange visit to teach in the USA and travelled by sea and train the 4,000 miles to Huron, a small town in South Dakota. In 1989 he wrote in a Penguin paperback copy of The Battle of Pollocks Crossing: ‘In 1938/39 I taught a year in Dakota. This is the background. The message is that we should be as wary of the Americans as we are of the Russians.’ Arriving home just after war broke out, he joined the RAF and was sent to West Africa to work on aerial photographic reconnaissance, then served as an Intelligence Officer. After the war he returned to teaching in the Midlands and settled back into English life, getting married and joining a cricket club. He had played football before the war for an extraordinarily successful village football team, but his main love was cricket and it is said that his batting was of minor county standard. The origin of his first dictionary may be found almost thirty years before it was published, in the Year Books of the Midlands Club Cricket Conference for 1950 and 1951. For the 1950 Year Book Carr wrote a 6-page ‘Miniature Anthology for Damp Days’ containing 28 entries on notable people who played cricket. In the following year he acted as joint editor of the Year Book and contributed more biographical details and small anecdotes, seemingly to fill blank spaces at the ends of pages. However the main feature was a full-page cartoon by Carr with illustrated biographical entries. At the end of the 1951 cricket season Carr left Birmingham to become headmaster of a new primary school in Kettering, where he lived for the rest of his life. There he edited the Year Books of the Northamptonshire County Cricket League and became involved with the local branch of the National Union of Teachers, writing articles for their magazine, the Northants Campaigner. Carr’s Dictionary of Extra-ordinary English Cricketers was an inspired idea. It contained 123 entries on cricketers or people who had commented on cricket, plus an entry on a horse that seemed to know when an innings was over and it was needed to pull the heavy roller across the wicket. A typical example was this: ‘Dr Heath DD, Headmaster of Eton, a perfectionist, who flogged the School XI, including (possibly unjustly) the scorer, when they returned from a defeat by Westminster School.’ The book was well reviewed and within a month had sold 10,000 copies. I was introduced to the extraordinary Mr Carr by my father, who had been compelled by his love of cricket statistics to point out some small errors in the dictionary. Although the errors are still there, the fact that Carr bothered to reply with a handwritten note of thanks was endearing. It made the writer seem less remote. Carr said that the idea for the next dictionary came from his wife, Sally, who proposed the subject of English Queens to coincide with Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee. This booklet contained 90 entries on English Queens, Kings’ Wives, Celebrated Paramours, Handfast Spouses and Royal Changelings, to give its full title. Carr commented, somewhat tongue-in-cheek I suspect, that he might have sold more copies if he had used the term ‘concubines’ rather than ‘handfast spouses’, but ‘I cherish my father’s memory’ (Carr’s father was a Methodist lay preacher). This dictionary, too, was published in 1977 and reprinted eleven times in Carr’s lifetime. The Dictionary of English Queens was also one of the last books published by the Quince Tree Press to be assigned an isbn. Perhaps Carr’s initial enthusiasm for this numbering system had waned and he had become cynical about the requirement to provide a free copy to the British Library and to any of the other copyright libraries that asked for one – not that he always did. In his last novel, Harpole and Foxberrow, General Publishers, A Business History (with footnotes), Emma Foxberrow writes a note to her business partner George Harpole when told of this statutory requirement: ‘The barefaced cheek! . . . If academic spongers want books let them cut off the wine tap to their High Tables and pay for them.’ The lack of a registered isbn or year of publication in most of his dictionaries makes it difficult to date them accurately. It is likely that he followed the Dictionary of Queens with a Dictionary of English Kings, Consorts, Pretenders, Usurpers, Unnatural Claimants and Royal Athelings. This in turn may have been followed by Welbourn’s Dictionary of Prelates, Parsons, Vergers, Wardens, Sidesmen and Preachers, Sunday-school Teachers, Hermits, Ecclesiastical Flower-arrangers, Fifth Monarchy Men and False Prophets, but I am guessing. Carr’s mother’s maiden name was Welbourn and his life-long interest in Christianity, the Bible and church architecture strongly suggests that he was the author. Carr was not the Quince Tree Press’s only dictionary writer. In February 1978 he published a Dictionary of Eponymists, 124 entries on people whose names were applied to ideas or things, compiled by A. J. Forrest. This was followed by Sandbach’s Dictionary of Astonishing British Animals, which contains 107 entries mostly on dogs, cats and horses, although Charles Kingsley’s slow-worm is mentioned, as is a tortoise presented by Captain Cook to the King of Tonga. The last non-Carr dictionary was a selection of misanthropic definitions written by the American journalist Ambrose Bierce for his Devil’s Dictionary. I suspect that Bierce and his dictionary were a source of inspiration to Carr, for Bierce was notable for his judicious and economical use of words as well as his social criticism and use of satire. For example: ‘Distance, the only thing that the rich are willing for the poor to call theirs, and keep’. In Huron in 1938 Carr had attended meetings of the local historical society. On his return with his wife and son in 1956 to teach for another year at the same school, he found the notes of the society’s meetings and used them as the basis for his Social History of the Old Timers (1957) and as the setting for the novel The Battle of Pollocks Crossing. To celebrate publication of the latter, Carr issued another small dictionary, Gidner’s Brief Lives of the Frontier, containing 88 entries on the men and women who lived between the Mississippi and the Rockies between 1810 and 1890. George Gidner was the young English narrator of the novel, who had travelled to Pollocks Crossing to teach at a local school and got caught up in the tragic events thattook place there, so Gidner is Carr himself. Other dictionaries were planned. In an interview in 1990 Carr mentioned that a dictionary of alchemists had been suggested, while in 1991 he said that he was thinking of compiling a dictionary of freedom fighters. This would probably have included Thomas Willingale, who saved Epping Forest from encroachment and to whom Carr dedicated one of his maps of Essex. Carr’s vision of a freedom fighter was the small man or woman who stood up to Authority and fought for social freedom, rather than a military leader. But after publishing his last novel, Harpole and Foxberrow, in 1992 and reissuing The Battle of Pollocks Crossing under the imprint of the Quince Tree Press the next year, he developed leukaemia and died in February 1994 aged 82. I cannot tell you if all the entries in Carr’s dictionaries are true. Carr said his customers liked the ‘social gossip of history’, but some entries sound so improbable as to be pure fiction. Or perhaps the reductive process of dictionary writing has stripped the facts to their unqualified essentials, which then just seem improbable. Did Pierre Trudeau, a scout pursued by Cheyenne Indians, really blind a rattlesnake with a squirt of tobacco juice when he was too scared to move in his hiding-place? Was Richard Daft, born in 1831, really the last practitioner of the underleg stroke, however that is played? Frankly I don’t care, but I suspect that, if challenged, Carr could have pointed to a source to confirm all his entries. When Carr was interviewed by a reporter from Vogue for their May 1986 issue, she cleverly asked him for a dictionary definition of himself. This is it: ‘James Lloyd Carr, a back-bedroom publisher of large maps and small books who, in old age, unexpectedly wrote six novels which, although highly thought of by a small band of supporters and by himself, were properly disregarded by the Literary World’.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 32 © Andrew Hall 2011

About the contributor

Andrew Hall works as an advisor on nutrition for the charity Save the Children. He has published a biography and bibliography of the Jersey artist Edmund Blampied and is compiling a bibliography of the work of J. L. Carr.

Some of Carr’s maps, dictionaries and small books are available from the Quince Tree Press, 116 Hardwick Lane, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, ip33 2le, or at www.quincetreepress.co.uk.