Can anyone reconcile us with death?

Michel de Montaigne, one of the great sages of the Renaissance, tried his best; and he was trying to reconcile himself as much as any readers he might have. ‘We must always be booted and ready to go,’ he writes in an early essay. To be ready we need to familiarize our- selves with this final destination. ‘So,’ he tells us, ‘I have formed the habit of having death continually present, not merely in my imagination, but in my mouth . . . He who would teach men to die would teach them to live.’

When in 1571 Montaigne retired from his position at the parliament of Bordeaux to the estate he had recently inherited, he wasn’t yet 40. Though no subject preoccupied him so much as death, he was still in good health, still free of the crippling kidney stones that would make his later years a torment. But to his surprise, all set as he was to dedicate the rest of his days to ‘liberty, tranquillity and leisure’, he found himself overwhelmed by depression. The only remedy he could think of was to write, as he explains to a friend in one essay:

It was a melancholy humour, and consequently a humour very hostile to my natural disposition, produced by the gloom of the solitude into which I had cast myself some years ago, that first put into my head this daydream of meddling with writing.

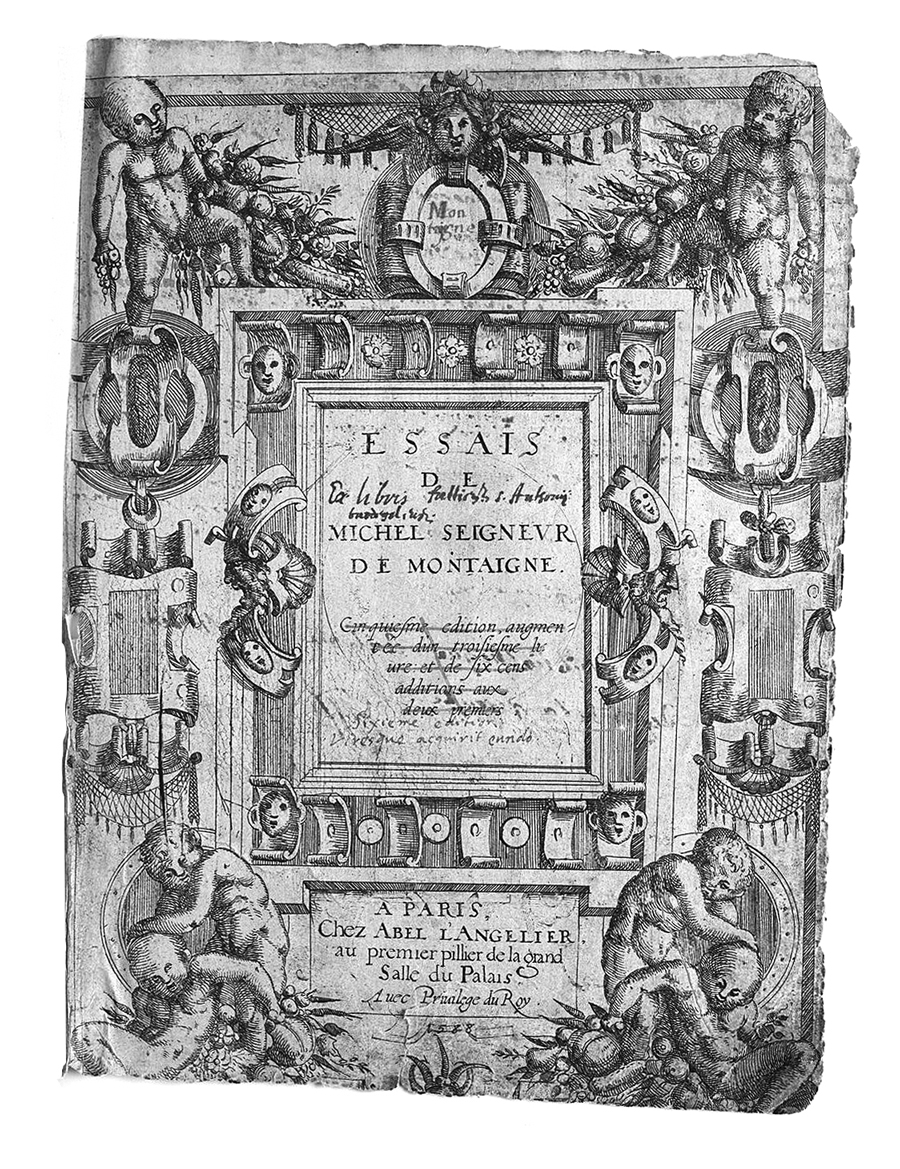

He could think of nothing to write about, however; so, with no other subject suggesting itself, ‘I offered myself to myself as theme and subject matter.’ If others could make portraits of themselves in pictures, why shouldn’t he portray himself with the pen?

In doing so, Montaigne takes as his watchword a motto from Plato: ‘Do what thou hast to do, and know thyself.’ To which he adds a characteristic rider: ‘Whoever would do what he has to do would see that the first thing

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inCan anyone reconcile us with death?

Michel de Montaigne, one of the great sages of the Renaissance, tried his best; and he was trying to reconcile himself as much as any readers he might have. ‘We must always be booted and ready to go,’ he writes in an early essay. To be ready we need to familiarize our- selves with this final destination. ‘So,’ he tells us, ‘I have formed the habit of having death continually present, not merely in my imagination, but in my mouth . . . He who would teach men to die would teach them to live.’

When in 1571 Montaigne retired from his position at the parliament of Bordeaux to the estate he had recently inherited, he wasn’t yet 40. Though no subject preoccupied him so much as death, he was still in good health, still free of the crippling kidney stones that would make his later years a torment. But to his surprise, all set as he was to dedicate the rest of his days to ‘liberty, tranquillity and leisure’, he found himself overwhelmed by depression. The only remedy he could think of was to write, as he explains to a friend in one essay:It was a melancholy humour, and consequently a humour very hostile to my natural disposition, produced by the gloom of the solitude into which I had cast myself some years ago, that first put into my head this daydream of meddling with writing.

Well now, leaving books aside and talking more simply and plainly, I find that sexual love is nothing but the thirst for enjoyment of that pleasure within the object of our desire, and that Venus is nothing but the pleasure of unloading our balls.This in the case of men, clearly, but he does not believe women are so different in their motivation. Males and females are cast in the same mould: ‘except for education and custom,’ he argues, ‘the difference is not great’. Like any other pleasure, though, sex ‘becomes vitiated by a lack of either moderation or discretion’. The key, as in so many other aspects of life, is to follow ‘the fine and level road that Nature has traced for us’. As he reached the end of his great undertaking – by the time of the second edition of the Essays (1588), he had written 107 of them, ranging in length from a single page to 170 pages – he laid increasing stress on the virtues of experience over intellectual knowledge. In his last essay, he gives us his conclusion: ‘Nothing is so beautiful, so right, as acting as a man should: nor is any learning so arduous as knowing how to live this life naturally and well.’ As for death, the subject to which he has returned so frequently, by his last essays his thinking has changed. ‘If you don’t know how to die, don’t worry,’ he comforts us. ‘Nature will tell you what to do on the spot, fully and adequately.’ You will only have to follow the example of his own farm workers at the time of a recent plague: ‘Here a man, healthy, was already digging his grave; others lay down in them while still alive. And one of my labourers, with his hands and feet, pulled the earth over him as he was dying. Was that not taking shelter so as to go to sleep more comfortably?’

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 69 © Anthony Wells 2021

About the contributor

Like Montaigne, Anthony Wells has retired from the world of work and has plans to write a book. There any comparison ends.