My brother, my sister and I grew up in a rambling farmhouse in Hampshire hung with pictures by friends of our parents, for they knew a wide range of artists and tended, naturally, to buy works by people they knew.

Some of these paintings seemed gloomy and frankly baffling, but those by Julian Trevelyan and his wife Mary Fedden danced with life and colour. Julian and Mary were among our favourite weekend guests, and we were particularly in thrall to Julian, who loomed over us from his immense height with his ‘craggy welcoming face and patriarchal beard’, in the words of his cousin Raleigh Trevelyan. He would spend hours entertaining us with comic drawings, notably of himself as Edward Lear’s ‘old man with a beard/ Who said “It is just as I feared!/ Two Owls and a Hen/ Four Larks and a Wren/ Have all made their nests in my beard.”’

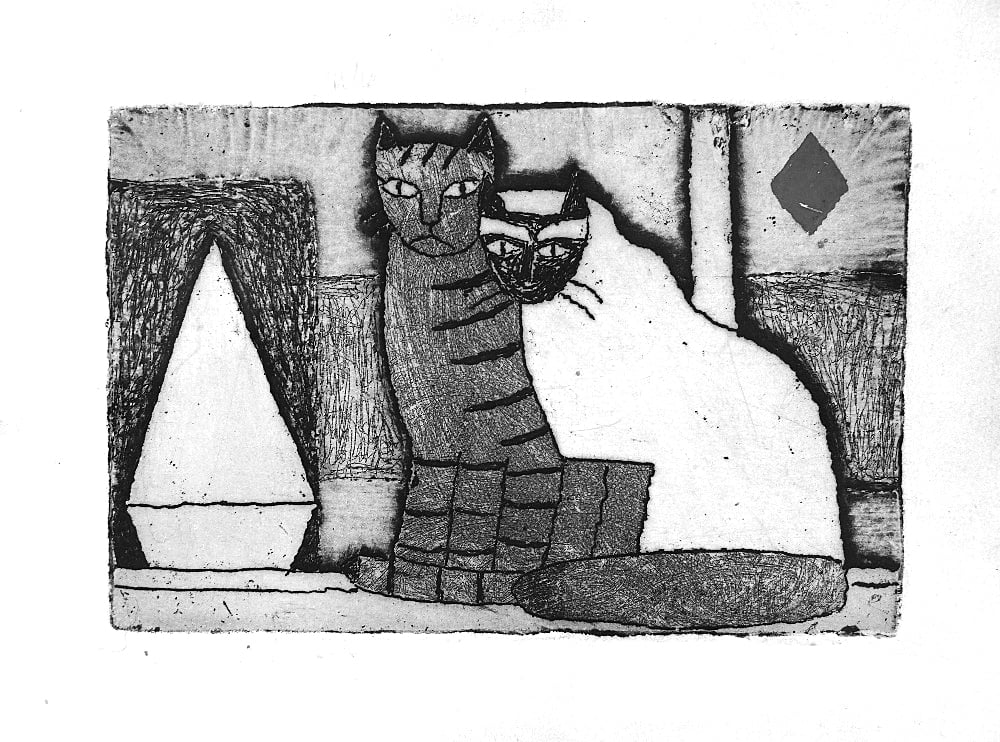

We looked forward, too, to their Christmas cards, etched by Julian and usually featuring their cats; in our dog-only household these alluring felines insinuated their way into our imaginations and took firm hold. I was to meet those cats and their successors when I moved to London in my twenties and took to visiting the Trevelyans in their studio at Durham Wharf in Hammersmith, two boathouses that seemed to float above the shifting tides of the Thames, interconnected by a luxuriant small garden.

The wonderful living-room with its broad window giving on to the ever-changing Thames waterscape is memorably described by Julian in his memoir Indigo Days (1957):

The walls, beams and ceiling we painted white, and we were enchanted with the ever-changing patterns of the reflections from the water on the ceiling whenever the sun shone. At times the sailing boats seemed almost to sail into the room and the gulls to swoop around the beams.

He captured this watery quality in a numinous painting of 1946, Interior, Hammersmith, which was exhibited in Paris and admired by Georg

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inMy brother, my sister and I grew up in a rambling farmhouse in Hampshire hung with pictures by friends of our parents, for they knew a wide range of artists and tended, naturally, to buy works by people they knew.

Some of these paintings seemed gloomy and frankly baffling, but those by Julian Trevelyan and his wife Mary Fedden danced with life and colour. Julian and Mary were among our favourite weekend guests, and we were particularly in thrall to Julian, who loomed over us from his immense height with his ‘craggy welcoming face and patriarchal beard’, in the words of his cousin Raleigh Trevelyan. He would spend hours entertaining us with comic drawings, notably of himself as Edward Lear’s ‘old man with a beard/ Who said “It is just as I feared!/ Two Owls and a Hen/ Four Larks and a Wren/ Have all made their nests in my beard.”’ We looked forward, too, to their Christmas cards, etched by Julian and usually featuring their cats; in our dog-only household these alluring felines insinuated their way into our imaginations and took firm hold. I was to meet those cats and their successors when I moved to London in my twenties and took to visiting the Trevelyans in their studio at Durham Wharf in Hammersmith, two boathouses that seemed to float above the shifting tides of the Thames, interconnected by a luxuriant small garden. The wonderful living-room with its broad window giving on to the ever-changing Thames waterscape is memorably described by Julian in his memoir Indigo Days (1957):The walls, beams and ceiling we painted white, and we were enchanted with the ever-changing patterns of the reflections from the water on the ceiling whenever the sun shone. At times the sailing boats seemed almost to sail into the room and the gulls to swoop around the beams.He captured this watery quality in a numinous painting of 1946, Interior, Hammersmith, which was exhibited in Paris and admired by Georges Braque, who subsequently invited Julian to tea to encourage his ambitions as a painter. Julian writes of stumbling upon the property in 1935 with his first wife, the potter Ursula Darwin: newly married, they were searching for a home where Ursula could erect her kiln on a plot of land or a derelict wharf, when they passed a ‘To Let’ sign outside a couple of dilapidated sheds on the river, the former studio and home of the sculptor Eric Kennington. ‘The tide was up and gulls flew screaming round us while tugs and sailing dinghies slapped about in the choppy water; we realized instinctively that this was our home and that we could live nowhere else.’ Though primarily an artist, both painter and experimental printmaker (he taught at Chelsea School of Art and the Royal College of Art, where he became Head of Printmaking), Trevelyan had a flair for writing, and was the author of essays on a wide variety of subjects, as well as several books about the artist’s life and calling, of which Indigo Days is the most personal and seductive. It covers the first half of his long and eventful life, three decades during which he developed his unique artistic personality and vision. This was distilled out of the bohemian, gregarious years he spent in Paris, London and the industrial north, during which he immersed himself by turns in surrealism, abstraction, landscape painting, satire and social comment. Add in his extensive wartime travels and his love of the exotic, and you have a boldly imaginative and original take on the world. The only surviving son of R. C. ‘Bob’ Trevelyan, a classicist and minor poet, and ‘a charming eccentric, at once childish, passionate, foolish and wise’, Julian inherited many of his father’s characteristics, notably his sociable nature. Bob Trevelyan’s circle of friends extended to Bloomsbury and beyond, Roger Fry, Bernard Berenson and Bertrand Russell prominent among them. Regular expeditions from their home in Surrey to the Trevelyan family seat, Wallington, in Northumberland, took the impressionable young Julian rumbling north by train through the gritty industrial heartland of Britain, instilling in him a lifelong love of factories, ‘vast railway stations, and valleys full of smoking chimneys’. Going up to Cambridge in 1929 to read English, he found it dominated by a generation of poets, and fell in with the likes of William Empson, ‘who rolled his great eyes round and round as he read his poems’, Malcolm Lowry, Julian Bell, who would tragically be killed in the Spanish Civil War, Kathleen Raine, ‘slight and beautiful as a flower’, and Humphrey Jennings, who kept Julian up to the mark with the admonishment, ‘That picture of yours hasn’t got 1931ness.’ It was Jennings who opened his eyes to contemporary French art. Paris seemed to be the epicentre of all that was exciting, so Julian abandoned his studies, packed his bags and moved to Montparnasse. There, he found himself among ‘a sort of international riff-raff of writers, painters, tarts and scroungers, all speaking together in bad French, [who] floated through the cafés, peering amongst the sea of tables on the pavements for a friend or acquaintance’. When not attending painting classes, or prowling round unknown corners of the city, he would frequent the legendary Café du Dôme – ‘the hub of the world, the cauldron in which all the races on this planet were being cooked into one gigantic bouillabaisse’. His neighbour was the American sculptor Alexander Calder, who was then developing his mechanized circus of wire acrobats, sword swallowers, tightrope walkers and chariots, which he would set to performing on a green baize circle in his studio. More often than not they came to grief, for ‘the frailty of his mechanisms was part of their charm. Over his bed were a series of strings that put on the light, turned on the bath, lit the gas under the kettle and so forth; often they failed to function and he would have to hop out of bed to fix them. When I last saw him,’ Julian writes, ‘he told me he was making a machine for tickling his wife Louisa in the next room.’ He also met the painter and engraver Stanley William Hayter, owner of the legendary studio Atelier 17. Here, he presided over a laboratory of printmaking by artists as various as Joan Miró, Alberto Giacometti, André Masson and occasionally Pablo Picasso – who was reputed to have flambéed his lunchtime steaks on the etching plates. The possibilities of this form of image-making fascinated Trevelyan, setting him on a course of experimentation that would make him one of the notable printmakers and teachers of his day. And the work of his surrealist contemporaries inspired a series of dream-like images that would culminate in his magical ‘Dream Cities’ of the mid-1930s. Ever interested in the workings of the subconscious, he later volunteered for experiments with the hallucinogenic drug mescaline, under the influence of which, he wrote, he had ‘fallen in love with a sausage roll and a piece of crumpled newspaper from out of the pig-bucket’. Back in London, the raging Spanish Civil War diverted his attention to politics, and thence to the experimental Mass Observation movement, dreamed up by the anthropologist Tom Harrisson to record the habits and concerns of the English, just as he had studied the peoples of Polynesia. The northern town of Bolton became the anonymous ‘Worktown’ and its pubs, shops and dance halls the sites of research. As designated artist for the project Trevelyan found himself trundling around with ‘a large suitcase full of copies of news-papers, copies of Picture Post, seed catalogues, old bills, coloured papers and other scraps’, applying the collage techniques he had learned from the surrealists to his depiction of that Depression-era industrial world. From Bolton they travelled to Northumberland to meet the Ashington miners, or ‘Pitman Painters’ as they are now known, whose talents and intellectual curiosity profoundly impressed Julian; a lively debate on the motion ‘That anyone can paint’ and a touring exhibition of their work followed. Then came war, and conscription to a camouflage unit, where he and the theatre designer Oliver Messel were initially charged with disguising pillboxes newly erected against the German threat. We camouflage officers were given full rein to our wildest fancies . . . and to this day, I believe, there exists [a pillbox] on the pier of St Ives that I had turned into an old Cornish cottage with cement-washed roof and lace curtains. Elsewhere I had erected garages complete with petrol pumps, public lavatories, cafés, chicken-houses and romantic ruins. Camouflage techniques took him on zany expeditions across Africa and the Middle East, where the tones and textures of the jungle, the desert, Cairo, Alexandria, Jerusalem and Lagos answered his appetite for the strange and exotic. When asked by his commanding officer to identify his religion at this time he defiantly wrote ‘Surrealist’. This is a painter’s memoir, informal, intimate, steeped in colour, vivid, deeply serious yet often comic in detail – and fresh as paint, still, after all these years.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 73 © Ariane Bankes 2022

About the contributor

Ariane Bankes co-curated the exhibition Julian Trevelyan: The Artist and His World at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester (October 2018 – February 2019), and still loves the nonsense verse of Edward Lear.