Asked which book has had the greatest influence on me, I’d like to nominate several for an Oscar, even though I already know which is going to carry it off. As a biographer – leaving aside the inevitable, incomparable Boswell’s Johnson – I was most inspired by two great two-volume biographies completed in the 1960s, when I was in my impressionable twenties: George D. Painter’s Marcel Proust and Michael Holroyd’s Lytton Strachey. Both biographers, through phenomenal research, had reached the souls of their subjects.

In history, A. J. P. Taylor showed me how chronicles could be made entertaining – though I admit there was sometimes justice in what Lord David Cecil said about him: ‘He will always sacrifice the truth for a paradox.’ In Herbert Butterfield’s little book on Napoleon, published in a Duckworth series in the year of my birth (1940), and in John Bowle’s The Unity of European History I saw how the threads could be drawn together in penetrating generalizations, all vivified by picturesque language. I learned passages from both men so that their cadence throbbed in my bloodstream. And the Pelican edition of Dorothy Whitelock’s The Beginnings of English Society, about the Anglo-Saxons, taught me how to bring different sources together to illustrate a single fact or idea – like training many searchlights on one spot.

But the book I unhesitatingly choose as my most powerful exemplar is William Gaunt’s The Pre-Raphaelite Tragedy. Like Butterfield’s Napoleon, it was published during the Second World War – in 1942. (Later the publishers changed the title to The Pre-Raphaelite Dream, after some self-righteous busybody complained that what the Pre-Raphaelite artists suffered could hardly be considered tragedy, compared with what ‘our lads’ were enduring in the war.) Just as Taylor’s books had shown me that history could be made very palatable, Gaunt’s book – and his later works on other artistic movements – disclosed the secret of making art history enjoyable, not merely an arid probing of what X owed to Y in technique or iconography. The secret was to understand X and Y as people, not just as artists. Such revelations are seldom irrelevant.

I first read the book when I was 16; later, Gaunt became a recurring figure in my life, cropping up unexpectedly like one of the incidental characters in Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inAsked which book has had the greatest influence on me, I’d like to nominate several for an Oscar, even though I already know which is going to carry it off. As a biographer – leaving aside the inevitable, incomparable Boswell’s Johnson – I was most inspired by two great two-volume biographies completed in the 1960s, when I was in my impressionable twenties: George D. Painter’s Marcel Proust and Michael Holroyd’s Lytton Strachey. Both biographers, through phenomenal research, had reached the souls of their subjects.

In history, A. J. P. Taylor showed me how chronicles could be made entertaining – though I admit there was sometimes justice in what Lord David Cecil said about him: ‘He will always sacrifice the truth for a paradox.’ In Herbert Butterfield’s little book on Napoleon, published in a Duckworth series in the year of my birth (1940), and in John Bowle’s The Unity of European History I saw how the threads could be drawn together in penetrating generalizations, all vivified by picturesque language. I learned passages from both men so that their cadence throbbed in my bloodstream. And the Pelican edition of Dorothy Whitelock’s The Beginnings of English Society, about the Anglo-Saxons, taught me how to bring different sources together to illustrate a single fact or idea – like training many searchlights on one spot. But the book I unhesitatingly choose as my most powerful exemplar is William Gaunt’s The Pre-Raphaelite Tragedy. Like Butterfield’s Napoleon, it was published during the Second World War – in 1942. (Later the publishers changed the title to The Pre-Raphaelite Dream, after some self-righteous busybody complained that what the Pre-Raphaelite artists suffered could hardly be considered tragedy, compared with what ‘our lads’ were enduring in the war.) Just as Taylor’s books had shown me that history could be made very palatable, Gaunt’s book – and his later works on other artistic movements – disclosed the secret of making art history enjoyable, not merely an arid probing of what X owed to Y in technique or iconography. The secret was to understand X and Y as people, not just as artists. Such revelations are seldom irrelevant. I first read the book when I was 16; later, Gaunt became a recurring figure in my life, cropping up unexpectedly like one of the incidental characters in Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time. It was Mr Sweatman, my art master, who first gave it me to read and it had me utterly enthralled. Mr Sweatman was meant to be conducting the art class, but he was obsessed by a school society called the Marionette Circle. He gave most of his attention to the few boys, members of the Circle, who arrived in class with tiny gibbeted figures dangling from their hands. He and they would disappear behind a lime-green screen, where the marionettes were made to perform their antics and danses macabres. Occasionally Mr Sweatman would emerge from behind the screen to bellow ‘Noisy!’ or ‘Guy Fawkes Night’ (a subject for us to paint). He was equally happy for the non-marionetteers to study art history; and with Gaunt’s book he found a perfect way of keeping me occupied. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in 1848, the ‘year of revolutions’, by a gang of artists: William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and four others. Strongly influenced by a group of German artists called the Nazarenes, and encouraged by the critic John Ruskin, they rejected Raphael as the ultimate model for painters, and also the academic school of art derived from Sir Joshua Reynolds – whom they called ‘Sir Sloshua’. Their aim was to ‘get back to nature’, with minute depiction of grass blades and tree blossom. Much of their inspiration was religious; and they broke down the barriers between ‘fine art’ and ‘craft’ by creating furniture, tapestries, stained glass, pottery, metalwork and printed books. Edward Burne-Jones became a leading member of the Brotherhood, and William Morris was influenced by them. A lonely child, I wished I could be a member of a ‘Brotherhood’ like the Pre-Raphs – later on, I had the same feeling about the Bloomsbury set and the Algonquin Hotel coterie in New York who laughed at Dorothy Parker’s wicked jokes. In 1956 I was just revelling in Gaunt’s story. I was not analysing how he produced his effects. But in rereading the book recently, half a century on, I have been admiring his skills and realizing how much he taught me. The first skill is one that all journalists have to pick up: that of plunging right into one’s story, grabbing the reader’s attention, rather than making his eyes glaze over with a long-drawn out mise en scène or unrolling of ancestry. You begin in the middle, then track back. The first chapter of The Pre-Raphaelite Tragedy is headed ‘A Child Wonder’: interest is sparked straight away – who is this child? The chapter is about prize-giving day at the Royal Academy in 1843. William Holman Hunt, then 16 – just the age I was when reading about him – becomes intent as the name of the gold medallist in the Antique School is announced: John Everett Millais. He it was whom Hunt had come especially to see: the famous child prodigy, who, a year or two earlier, at the age of ten, had been the youngest student ever to get into the Academy; whose miraculous talent was the talk of the whole art world.Standing up was a quaint, angelic little creature – an Early Victorian angel. Long light curls fell over his goffered collar . . .I had to look up ‘goffered’ in the dictionary: pleated, crimped, ruffled. Gaunt’s prose is wonderfully varied. It can be luscious; but it can also become staccato. This is how he introduces Dante Gabriel Rossetti:

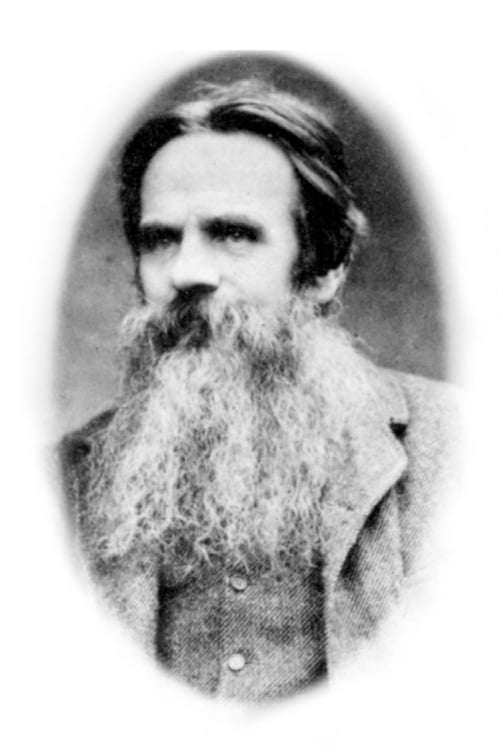

It was at this point and in the year 1847 that a strange being crossed the path of the two young artists [Millais and Hunt]. A fascinating, careless, wayward, capricious, irreverent, dominating being. A London Italian. Not even a professional painter – a sort of poet or a poet and something of a painter as well. Spouting endless verses, some of them his own. A genius, perhaps, in a way, but not a straightforward way like Millais’. Full of contempt for authority. Cascading out words, beautiful words, grotesque and invented words, slang words . . .Gaunt manages to achieve two things, apparently contradictory, at the same time. He conveys, with emotion, why the Pre-Raphaelites thought and behaved as they did; but he also maintains an objectivity. A highly developed sense of humour is one of his chief assets; he is always prepared to laugh at the Pre-Raphaelites, inviting us to share the joke, as in this passage: [Rossetti] would shoot off at a tangent and draw up a memorandum on immortality: making out a list of immortals who would constitute ‘the whole of our creed’ and denoting the grade of each by one, two or three stars. Jesus Christ had four: the Author of Job three, Homer two, and the list included Joan of Arc and Mrs Browning, Kosciusko and Columbus, Tennyson (one star) and King Alfred (two). Thanks to Gaunt, I became obsessed with the Pre-Raphaelites, entered their dream-world; and, like him, they seemed to crop up in my life. My grandfather had been Burne-Jones’s postman, delivering letters to his house, The Grange, in Fulham – a building destroyed in the 1950s. My maternal grandmother was a friend of Millais’s son who kept a pub near the Wallace Collection. At university I saw the badly faded murals that Morris and Burne-Jones had painted in the still gas-lit Oxford Union – their condition had provoked the pun on O tempora, O mores!, ‘O tempera, O Morris!’ And I and some college friends visited Kelmscott Manor, the ‘Nowhere’ of Morris’s book News from Nowhere. Later, the writer Diana Holman-Hunt, the artist’s granddaughter, was a friend. In a rag-and-bone shop in the North End Road, near the site of the demolished Grange, I bought for 10 shillings some cartoons for murals by a Pre-Raph hanger-on called Frederick Shields. I swapped them for some seventeenth-century pottery with a college friend. Through a friend of my mother I was introduced to Mrs A. M. W. Stirling of Old Battersea House (the seventeenth-century mansion later owned by the American tycoon Malcolm Forbes, a major collector of Pre-Raphaelite works). I was in my twenties, she in her nineties. She was the sister-in-law of the great potter William De Morgan, a friend and associate of Morris. The house was full of his lustre wares, and there were also allegorical paintings by Mrs Stirling’s late sister, Evelyn Pickering. These were so Pre-Raphaelite in spirit that unscrupulous dealers used to alter the artist’s initials E. P. to E. B. J. and try to pass off the works as by Edward Burne-Jones. By the time I went up to Oxford, in 1959, I knew enough about ceramics to submit an article to The Times. It was about a minor Staffordshire potter, John Turner, who was to be the subject of my first book. The article was accepted by Iolo Williams, the paper’s Museums Correspondent, himself an authority on water-colours. Just as I was about to leave Oxford, in 1962, I read an obituary of Williams. I wrote to the Editor of The Times: ‘I hope it is not indecently early to enquire whether this has created a vacancy lower down the scale’ – meaning, could I have Williams’s job. After four interviews I was told: ‘You can’t walk straight into the job of Museums Correspondent; but we will appoint you to a traineeship and you will have that post eventually. In the meantime, William Gaunt will act as a stopgap.’ I was in my twenties, Gaunt in his sixties; but in this curious way he became, as it were, my understudy. In those days I often got invited to gallery private views. Always, Gaunt was there, swigging wine and looking rather like a punch-drunk boxer. In 1975 I wrote an article in The Connoisseur about Gaunt, to mark his seventy-fifth birthday. Tribute had already been paid to him in The Spectator by Benny Green (better known as a writer on jazz), who wrote of him: ‘I have no hesitation in saying that over the years his books have been the source of more pleasure and instruction to me than any other ten books on painting whose existence I know of.’ In my anniversary piece, which was accompanied by a photograph of the bespectacled Gaunt when young, I noted that in 1914, when he was a schoolboy at Hull Grammar School, he had won a Connoisseur prize for an essay. I chose just one passage from his writings to represent him. It was that in which he described how Holman Hunt painted The Scapegoat on the shore of the Dead Sea. He evoked the sea:

The swimmer in this leaden element would roll over and over, feet above head, driven by the current against the dead arms of submerged trees: smarting from the salty bite. The caves of Oosdoom (the ancient Sodom) were hung with stalactites of curious form and if you shouted ‘Remember Lot’s wife’ the rumour of sound hurtled round every silent crag and repeated with morbid accuracy, ‘Remember Lot’s wife.’In that year I tried to obtain Gaunt a public honour. A CBE would have been nice; but I didn’t carry enough guns for the task and he received nothing. He died in 1980. His benevolent spirit haunts me still. Only this year I was twice reminded of him. First, I decided to begin work on a book about the restaurateur X. Marcel Boulestin, who after being secretary to Colette’s husband Monsieur Willy, and an actor with Colette, opened a restaurant in London in the 1920s. I found that The Studio had published a superb description of the restaurant’s décor, by the young Gaunt. More recently still, I gave a talk on ‘John Betjeman and Architecture’ at the Art Workers’ Guild in London, mentioning among other things the poet’s admiration of, and friendship with, the arts and crafts architect C. F. A. Voysey. I found that the meeting’s organizer, Alan Powers, had put out on a table a masterly painting of Voysey attending a session of the Guild. In a caricature-like style – as it were, H. M. Bateman out of Rowlandson – it was signed ‘William Gaunt’.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 15 © Bevis Hillier 2007

About the contributor

Bevis Hillier is best known as the author of the three-volume authorized biography of John Betjeman. He is also infamous for having conned A. N. Wilson into printing a spoof Betjeman love-letter in his later life of the Laureate, incorporating a very rude acrostic about Wilson.