Notes from Town and Country

From Hazel, Highbury, 23 October 2020

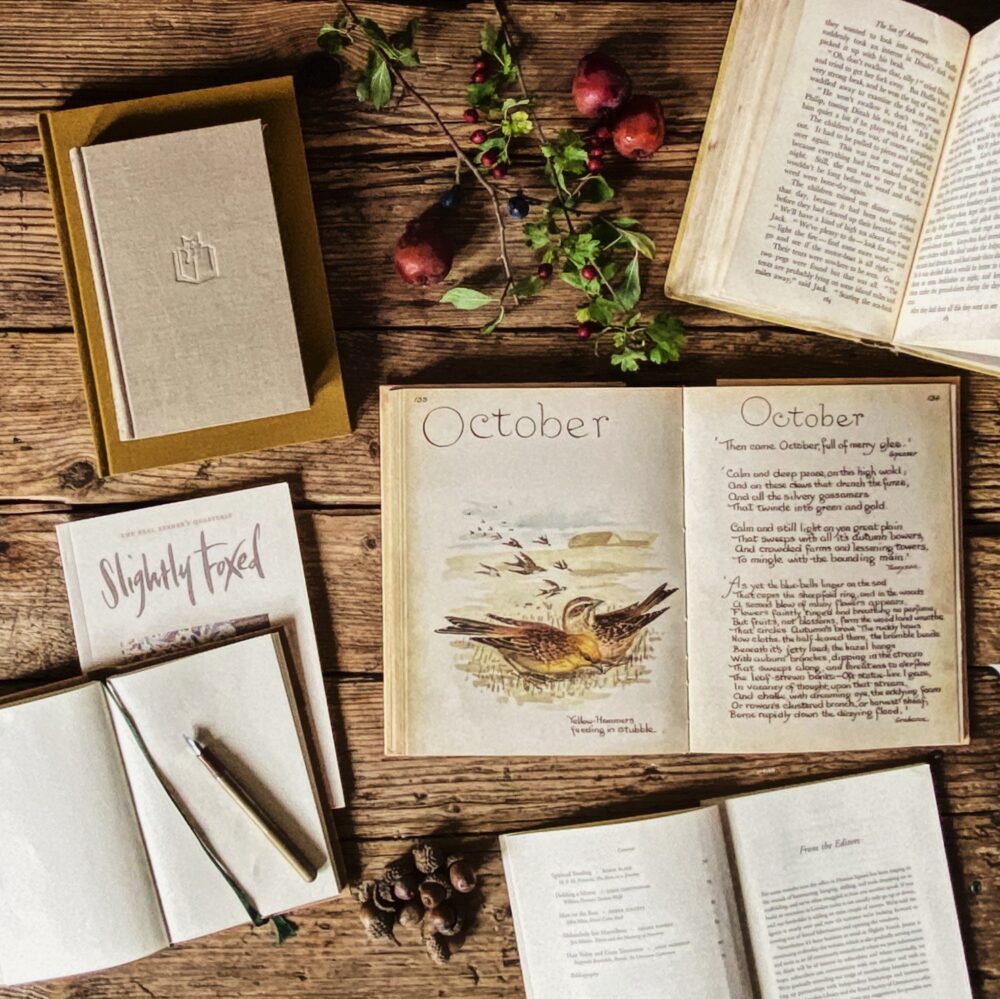

A Brief Pageant of English Verse

I won’t arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

I’ll sanitize the doorknob and make a cup of tea.

I won’t go down to the sea again; I won’t go out at all,

I’ll wander lonely as a cloud from the kitchen to the hall.

There’s a green-eyed yellow monster to the north of Katmandu

But I shan’t be seeing him just yet and nor, I think, will you.

While the dawn comes up like thunder on the road to Mandalay

I’ll make my bit of supper and eat it off a tray.

I shall not speed my bonnie boat across the sea to Skye

Or take the rolling English road from Birmingham to Rye.

About the woodland, just right now, I am not free to go

To see the Keep Out posters or the cherry hung with snow,

And no, I won’t be travelling much, within the realms of gold,

Or get me to Milford Haven. All that’s been put on hold.

Give me your hands, I shan’t request, albeit we are friends

Nor come within a mile of you, until this trial ends.

This rather brilliant little verse arrived in the SF inbox recently from our contributor Alastair Glegg. No one seems to know who wrote it, but it certainly strikes a note with me. Out of my study window I can see fat woodpigeons pecking at the red berries on the hawthorn tree at the bottom of the garden, and the grass in the park is strewn with conkers. Autumn brings on dreams of misty lanes and convivial drinks in country pubs, but not this year, alas.

Around here the sense of claustrophobia has been increased by a new policy known as ‘quiet streets’. In various parts of London, councils have installed huge planters – some of them already overturned by furious motorists – blocking off residential side roads and nifty short cuts. As a result the main roads are gridlocked with stationery cars, idling with their engines running. Near total paralysis has struck Euston Road, one of our main escape routes out of London.

The first shock of a great earthquake had, just at that period, rent the whole neighbourhood to its centre. Traces of its course were visible on every side. Houses were knocked down; streets broken through and stopped; deep pits and trenches dug in the ground; enormous heaps of earth and clay thrown up; buildings that were undermined and shaking, propped by great beams of wood . . . Everywhere were bridges that led nowhere; thoroughfares that were wholly impassable . . .

That’s Dickens describing the coming of the railways to London in Dombey and Son, but it could equally describe what’s happening to large areas around Euston Station which are being demolished to make way for that other controversial project, HS2.

In an effort to combat lockdown lethargy we set off last weekend to Alexandra Palace. You can’t live in this part of North London without being aware of this vast structure. Set on the rise between Crouch End and Muswell Hill – those Victorian and Edwardian suburbs so beloved of John Betjeman – and surrounded by a large landscaped park, it looms over the surrounding area like some prehistoric beast that has somehow survived into the present, though ‘white elephant’ might be a better description.

The original Ally Pally, as it’s always known, was planned as a ‘People’s Palace’ to rival Prince Albert’s Crystal Palace. It was finally opened in 1873, and sixteen days later burned to the ground. Two years later a second spectacular palace was opened, named after the popular Princess Alexandra of Denmark who in 1863 had married the future King Edward VII. Within its cavernous interior was a Great Hall seating 14,000, a Willis Organ, a Palm Court, a theatre modelled on Drury Lane, a concert room seating 3,500, and various museums and banqueting suites. The park was redesigned to include a trotting ring and cycle racing track, a cricket ground, ornamental lakes, a Japanese village, tennis courts, a permanent fun fair and an open-air swimming pool.

Since those first glory days the fate of Ally Pally and its upkeep has been a long-lasting bone of contention. The threat of demolition has hung over it, parts of the park have been sold off or redesigned, and it has changed hands several times. During the First World War it was requisitioned as a transit camp for Belgian refugees, in 1934 part of it was leased by the BBC who made the first TV transmission from an aerial attached to the south-east tower. It was bombed during the Second World War and Gracie Fields sang there (though not simultaneously), and in 1974 there was another major fire which gutted or severely damaged large parts of the building.

Haringey Council took it over in 1980 and with the help of the GLC and £42 million of insurance money, began a gradual restoration. Now it is very much a local go-to place and normally the building would be busy with community activities, entertainments of all kinds, and a bar and a restaurant. Now of course it is closed – though on TV the other night we did watch the first ever drive-in version of La Bohème, put on by English National Opera in the Ally Pally car park (see amusing Guardian review). So we walked along its massive frontage gazing out eastwards over Wood Green and on towards the far towers of Canary Wharf, walked in the hilly park, and sat in the café by the lake, watching the passing scene of dog owners and walkers and runners and families circling the central island in swan-necked pedalos. Not a convivial drink in a country pub but inspiriting all the same to see how yet again this old phoenix has risen.

*

Attempts at a general clear-out continue, and my husband has just entered the room to say that he has been trying to book an appointment online at our local recycling centre and his efforts have now been answered by an instruction in Chinese (or Japanese?) and he has neither language. We decide to have lunch and accept it as one of the mysteries of this baffling new Covid world, in the same category as trying to contact one’s GP or working out what’s happening to the Archers.

From Gail, Manaton, 23 October 2020

A few weeks ago we took ourselves off to Tewkesbury, which I’ve long wanted to visit because it was the birthplace of John Moore, author of the Brensham trilogy which we’ve reissued as Slightly Foxed Editions. In the first volume, Portrait of Elmbury, Moore records his childhood in this small English market town on the confluence of the River Severn and the River Avon. Before the advent of mass travel, mass media and the changes wrought by two world wars, it had a distinct and sturdy life of its own.

Much of course has changed since Moore’s day but it’s still possible to see Tudor House, where he lived as a child. It’s a magnificent building, three storeys of black-and-white timber and diamond-shaped leaded windows. As I stood at its entrance I tried to imagine Moore and his sister, their noses pressed against the windowpanes,

gazing out with lively interest and eager anticipation at the black and gaping maw of Double Alley, which was the name of the slum opposite us . . . even among Elmbury’s slums, Double Alley was something to be wondered at . . . A fair example of its inhabitants would be Mr and Mrs Hook. The domestic disagreements of this hot-tempered couple always took place in ‘coram populo’, at the street entrance to the Alley . . . Mr Hook would return, lurching and staggering, from his festivities, and Mrs Hook, hearing his approach or being warned of it, would rush out to greet him with blows and blasphemy; and in a confused flurry of attack and counter-attack they would disappear together into the alley’s dark maw . . .

In Moore’s day the town was threaded by dozens of these alleys, and though many have since disappeared beneath modern development there are still about thirty of them left. They are much more respectable now, which in a way is a pity, but even so we spent a happy hour weaving our way up one alley and down the next ‒ Yarnell’s Alley, Fish Alley, Hughes Alley, Fletcher’s Alley ‒ past medieval timbered houses, small well-tended gardens, a Baptist chapel, and a graveyard where one of Shakespeare’s relatives is said to be buried. So much history compressed into small spaces.

History seems to be everywhere in Tewkesbury. We were staying in the gatehouse that sits to one side of the Norman Abbey and ate our breakfast beneath the fourteenth-century carved stone heads of angels and monks. We spent another morning following a trail that winds between houses and gardens through fields to the south of the town. Here, on 4 May 1471, the forces of the Yorkists and Lancastrians met in one of the last battles of the Wars of the Roses. There’s a brilliant account of the battle in Ronald Welch’s Sun of York. Sitting in the Abbey on Sunday morning, gazing up at the delicate tracery of its fan vaulting and listening to the organ playing, it was hard to imagine so much bloodshed just beyond its walls.

Now it’s October and we’re home again, well and truly in the midst of Keats’s season of mists and mellow fruitfulness. For several weeks, on our daily walk to collect the newspaper from the bus-stop, we’ve been pausing by one particular tree on the bridlepath. It’s a Cercidiphyllum japonicum, and in spring its delicate leaves turn from bronze to pale green. Then, with the advent of autumn, the leaves turn again, to yellow, orange, pink, and as they turn the air is filled with the smell of caramel.

Down in the orchard the branches of the apple trees are bowed by the weight of their fruit and we’re bracing ourselves for a weekend of picking and pulping and pressing. In past years we’ve used a manual crusher to turn the apples into pulp but it’s an awful sweat cutting them all up and then wrestling with the cast-iron handle that turns the cogs of the crusher. This year, remembering blisters and aching arms and backs, I splashed out and bought an electric version. An extravagance, I know, but twenty trees’ worth of apples takes a long time by hand.

We’ve had another harvest too. One morning we woke up to see several white rings in the grass of the field opposite. I’m always uneasy about identifying mushrooms but there was no mistaking these – dozens of horse mushrooms, some as big as dinner plates, and all in perfect condition. So it was mushrooms on toast for lunch and several pots of soup for the freezer.

Haze, your visit to Ally Pally brought an ache to be with you both as you sat in the cafe, watching the passing scene, though I must confess I had to look up swan-necked pedalos, unknown in conventional Marlborough.

Gail, while you were buying a new electric apple machine for your twenty trees, we were removing our two apple trees to replace them with stepover apples for old age gardening! At the foot of our compost bins was a clump of enormous mushrooms. They looked delicious but, longing to cook them, I chucked them uncertainly on to the heap. I wish I’d had your knowledge.

A quick note to say how much I enjoyed “A Brief Pageant . . .” It made me smile and also caused me to remember how much English verse I have remembered from my school days.

I just want to say a simple thank you to all at SF for all of your efforts to maintain a sense of normality and peace in these turbulent times. There seems to be so much hate and criticism on the radio and in newspapers. None of which is helpful and morale raising. You do a wonderful job and all the observations of the natural world are a great solace and a balm to the soul!! I love the poem. Very clever. THANK YOU.

What an apt poem, I love it !

The collecting of apples for juicing is an autumn ritual. For many years we crushed them with an ancient barrel gadget encircled by hundreds of nails, and then folded them into “cheeses” of sacking which were then stacked and squeezed by an ancient oak press. Next up for some years was an industrial veg grinder, followed by a French grape press, and finally (in retirement) off they went to a local orchard where they press individual owners’ apples, and bottle and pasteurise the result. Not so romantic, but it does stop the unintended explosions that sometimes occurred with the previous incarnations. There is simply nothing more seasonal than mulled apple juice – delicious!

BTW – love the stationery cars – full of writing paper and greetings cards presumably?