There is something about a memoir describing a young person starting their first job that makes an older reader’s heart beat faster with sympathetic recall. Especially when it’s funny and beautifully written like Joanna Rakoff’s My Salinger Year (2014).

The year in question is 1996 when, aged 24, she lucked into an assistantship at one of New York’s most distinguished literary agencies. Joanna doesn’t even know what a literary agency does and, furthermore, has lied about her typing speed. And the porkies don’t end there. Her parents think she’s sharing an apartment with an old college friend (female). In reality she’s living with Don, a penniless charmer and unpublished Marxist novelist. His only job is watering the plants at Goldman Sachs. So, on an intern’s salary, she is paying off her student loan and all their rent for a hovel heated by the oven. At this point a cry of recognition must go up from most readers. Yes! Broke, hungry and freezing! The default setting for your first job!

And yet. And yet. From that very first January day, snow piled six feet high outside on the sidewalks, Joanna is enchanted by this strange, time-warped world she’s strayed into. A literary agency, she rapidly discovers, is where creativity meets commerce. The author writes the book, the publisher publishes the book. In between, literary agents sell serial rights, represent the author and negotiate the advance for the next book. In addition, Joanna, an English graduate, discovers she has wandered into the literary annex of Ali Baba’s Cave. The dimly lit, Turkish-carpeted offices are packed, floor to ceiling, with shelves of first editions of the works of major American writers since 1930. The Agency has represented them all.

But why are the business practices of this sophisticated, successful agency so firmly fixed in the mid-1940s, an era of ‘steamship travel and fox fur capes’ as Joanna vividly describes it? Why do the staff accept working conditions so stuck in the past that both Dickens’s Jarndyces would feel entirely at home there? Take Hugh, a kindly agent who wants to help Joanna. A visit to his office is . . . revealing.

Hugh sat behind a pile of paper high enough to obscure his chest and neck, letters opened and unopened: crinkled envelopes, yellow carbon copies and the black sheets of the carbon paper that had created them. A mess so vast and unfathomable I shook my head to make sure it was real.

‘I’m a little behind,’ he said. ‘Christmas.’

‘Oh,’ I said.

Now keen-eyed readers will have spotted the trigger word here and it is ‘carbon’! Yes, the Agency still uses carbon paper which can only mean that in this Year of Grace 1996, the year the technology industry gave us the MP3 player and the use of emojis, the Agency does not use computers. Hence the carbons, the endless filing cabinets and the desks snowed under with correspondence. Also Joanna’s Selectric typewriter, which emits a typing noise like low-level machine-gun fire.

Mysteriously the agents accept and are of a piece with their surroundings. Joanna’s female boss – never named, with a low, patrician voice – arrives at work in a ‘whiskey mink, her eyes covered with enormous sunglasses’. Plus a cigarette-holder which is absolutely not a prop. These people smoke like chimneys. The strangeness of this new, smoke-filled world is spelt out by Joanna’s first conversation with her boss. Far from being the usual meet-and-greet about when she should take her lunch break, it’s a stern, CIA-style briefing prefaced by the ominous words: ‘We need to talk about Jerry.’ ‘Jerry who?’ wonders our green-as-grass intern, fortunately only to herself. ‘Seinfeld?’

Drawing deeply on her cigarette, the agent continues:

‘People are going to call and ask for his address, his phone number. Reporters will call. Students. Graduate students. They’ll say they want to interview him or give him a prize or an honorary degree . . . They may be very persuasive, very manipulative. But you must never, never, never give out his address or phone number. Just get off the phone as quickly as possible.’

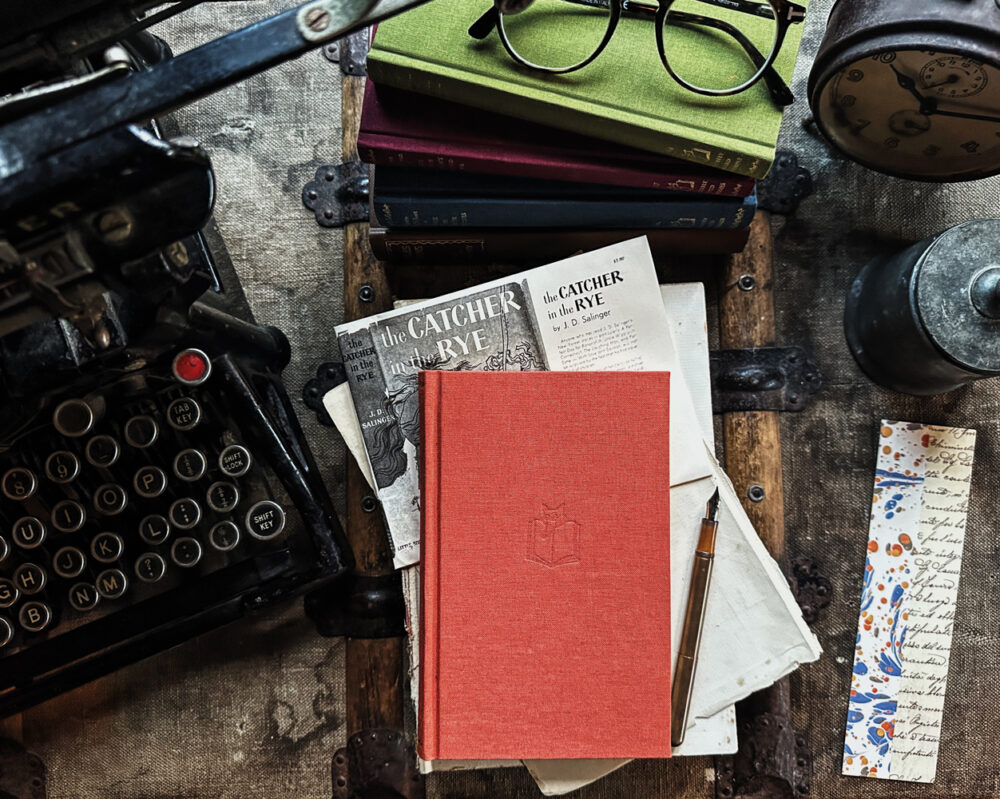

Promising to honour this strange omertà, Joanna returns to her desk and continues to type letters, rather badly (she has a problem with margins). It’s only when she raises her eyes to the titles in the bookshelf opposite that the penny drops. The Catcher in the Rye. Franny and Zooey. Nine Tales. J. D. Salinger.

‘Oh, I thought. That Jerry.’

Enter, stage left, the kindly Hugh, bent double under an enormous pile of unopened letters and with a hopeful look on his face. ‘These are today’s fan letters to Salinger. We always get a lot after Christmas. Perhaps you could deal with them?’ Almost struck dumb with dismay, she still has the wit to ask: ‘Is there a pro forma letter?’

Yes, there is, dated 1963, the year in which J. D. Salinger gave up hope of being able to reply to his fan mail. So all letters are to be answered by the Agency, stating firmly that it is not their policy to forward them.

A bot could accomplish this task without difficulty. But not Our Girl, who reads each letter and is undone by the pain and longing expressed in them. She replies to every single one, usually with the pro forma letter but sometimes, fatally, writing a personal letter herself. (You would think people would be grateful. Not so teenage girls, who write back, livid, and demand to be properly put in touch with their hero.) The unifying thread that binds together all this wildly disparate correspondence is the writers’ absolute certainty that Salinger is their friend.

The sheer volume of those letters made me want to know the back story of J. D. Salinger. Why, in 1996, is fan mail continuing to pour in about a novel written forty-five years before? Many post-war novels grace the Agency shelves, but none are still selling a million copies a year like The Catcher in the Rye, or, furthermore, retain an absolute moral authority with each succeeding generation. Let me be upfront and say that, when I read this book in my teens, I could get no purchase on it at all. I thought it must be a chap’s book. It was only after reading Ian Hamilton’s excellent biography In Search of J. D. Salinger (1988) that I understood for the first time what the book was really about.

Jerry Salinger was a boy from a well-off background who knew he wanted to write and honed his craft vigorously throughout his elite, fractured education. His reputation as an aloof smart alec bothered him not at all, particularly as, by his early twenties, he was having stories accepted by Esquire. Pearl Harbor prompted him to volunteer. By 1944 he was in Europe. We know he had already written the opening chapters of The Catcher because, preposterously, he had them with him as he waded ashore at Utah Beach in the D-Day landings of June 1944. His Twelfth Division was one of the ones that liberated Paris.

Though there is a photograph of Salinger during a lull in the fighting, that picture is misleading. His was an indescribably terrible war. In the late autumn of 1944 he fought in the battle for Hurtgen Forest against an enemy made crazed and desperate by the thought of defeat. Then his regiment moved straight on to the infamous and bloody Ardennes offensive, the so-called Battle of the Bulge. There he experienced 200 days of continuous fire and appears to have had a breakdown. The smart-alec preppie was shocked into becoming someone different.

The Catcher in the Rye came out in 1951. Reading it now, I can see that the book is fuelled entirely by his grief and horror about the war he’s witnessed. The older combatants who write to him know he’s seen what they saw: for young men and women the lasting appeal of the book is the protagonist Holden Caulfield’s struggle to find a way of living that isn’t false or inauthentic.

The fan letters come from all over the world. All the Scandinavian countries. Many from Japan where whole forests have given their lives to provide Hello Kitty stationery for teenage girls to confide that they are looking for a boy like Holden Caulfield. Teenage American boys are well represented. They, too, despise the falseness and inauthenticity of the adult world. On a more sombre note, there are long letters from Second World War veterans of Salinger’s own age who shared his wartime experience. They write because they cannot forget the comrades who died in their arms, and the cadaverous bodies they saw in the death camps they liberated. Then there are the dark but thankful letters from people whose loved ones had found solace in Salinger’s books during a long struggle with cancer.

Braced against this tsunami of grief is one frail English graduate wearing a Black Watch tartan skirt and penny loafers. She does her very best. But her learning achievement of the year is discovering what Holden Caulfield found out: you can’t be responsible for healing all the hurt in the world.

Other lessons are also learnt. The most important thing is that, to become a writer, she can’t spend her life taking care of other writers. On a more joyful note, she gets to meet J. D. and he is cordial and friendly, even if he does sometimes call her Suzanne (he’s deaf.) And she’s there to witness the earth-shattering moment when technology crashes through the Agency doors with the arrival of a computer, singular. Finally, in matters of the heart, she realizes that the unpublished Marxist boyfriend is never going to make a life partner.

I loved this book and feel sure you will. Read it for your own pleasure, but with the additional satisfaction of knowing that Christmas present dilemmas for grand- and godchildren are now solved forever.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 81 © Frances Donnelly 2024

About the contributor

Frances Donnelly still lives on the Norfolk/Suffolk border and considers herself very fortunate.