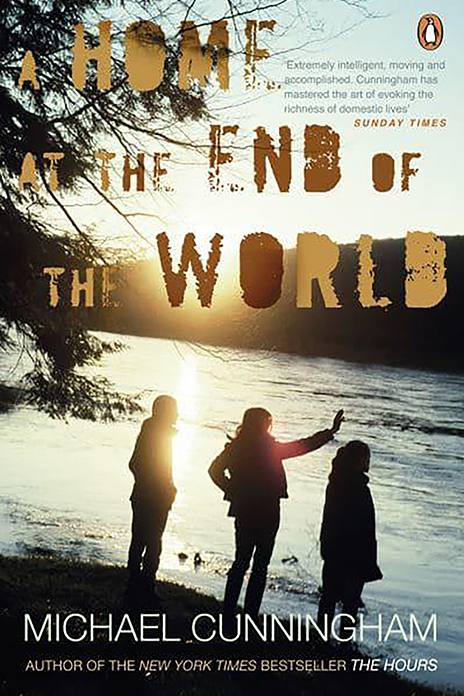

Michael Cunningham is best known for his third novel The Hours (1998), later made into an equally successful film. But it’s his second, A Home at the End of the World (1991), which I consistently reread, knowing that its lyrical voice and profound insights will never fail to move me.

The story is told by four voices, two male and two female, with such tenderness and sympathy that it’s clear how much the author loves his flawed characters. Bobby and Jonathan are young men growing up during the 1960s and ’70s, in Cleveland, Ohio. Bobby has a conventionally happy home with an adored older brother. His life has been infused by the ordinary and the actual – meals, school, parents. But by his early teens, his life has imploded. His mother and brother are dead and his father has become an alcoholic. At Junior High, spaced out and almost feral, he meets clever, self-contained Jonathan who lives with his mother and father. They bond immediately and ferociously.

It was the kind of reckless overnight friendship particular to those who are young, lonely and ambitious. Gradually, item by item, Bobby brought over his records, his posters and his clothes to my room. He was escaping from a stale, sour smell of soiled laundry, old food and a father who moved with drunken caution from room to room.

It’s not that Jonathan’s family becomes Bobby’s. It’s that Jonathan has become Bobby’s family.

The whole question of family – how it makes and mars you in almost equal measure – is one of Michael Cunningham’s main concerns. But as a gay man, the questions he asks transcend the norms of the nuclear family. Who are our real family? Is it those to whom we’re connected by blood? Or is it possible, through friends and lovers, to create a reconfiguration which answers our real emotional needs?

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inMichael Cunningham is best known for his third novel The Hours (1998), later made into an equally successful film. But it’s his second, A Home at the End of the World (1991), which I consistently reread, knowing that its lyrical voice and profound insights will never fail to move me.

The story is told by four voices, two male and two female, with such tenderness and sympathy that it’s clear how much the author loves his flawed characters. Bobby and Jonathan are young men growing up during the 1960s and ’70s, in Cleveland, Ohio. Bobby has a conventionally happy home with an adored older brother. His life has been infused by the ordinary and the actual – meals, school, parents. But by his early teens, his life has imploded. His mother and brother are dead and his father has become an alcoholic. At Junior High, spaced out and almost feral, he meets clever, self-contained Jonathan who lives with his mother and father. They bond immediately and ferociously.It was the kind of reckless overnight friendship particular to those who are young, lonely and ambitious. Gradually, item by item, Bobby brought over his records, his posters and his clothes to my room. He was escaping from a stale, sour smell of soiled laundry, old food and a father who moved with drunken caution from room to room.It’s not that Jonathan’s family becomes Bobby’s. It’s that Jonathan has become Bobby’s family. The whole question of family – how it makes and mars you in almost equal measure – is one of Michael Cunningham’s main concerns. But as a gay man, the questions he asks transcend the norms of the nuclear family. Who are our real family? Is it those to whom we’re connected by blood? Or is it possible, through friends and lovers, to create a reconfiguration which answers our real emotional needs? There are two female voices in the narrative, the first of whom is Alice, Jonathan’s mother. Without pleasure she recalls: ‘Our son brought Bobby home when they were both thirteen. He looked hungry as a stray dog and just as sly and dangerous.’ But Jonathan’s father Ned, who runs the local cinema, has a different take. ‘That kid’s in a bad way,’ he remarks, after seeing Bobby ravenously demolish one of Alice’s exquisite meals. ‘He’s a boy with no one but a father, growing up half wild. We have enough resources to give shelter to a wild boy, don’t we?’ So Bobby stays and sleeps in Jonathan’s room. Alice, not happy in her marriage and who’s always prized her closeness to her only child, finds that that part of her life is abruptly over. She’s even less happy when she discovers her son and his friend engaged in a rudimentary sexual relationship. But Bobby becomes a fixture and Alice, to her own surprise, enjoys teaching him how to cook. Jonathan leaves home for college. Bobby tries to open a restaurant, fails, then eight years later follows Jonathan to New York. At this point in the story the final narrative voice is added: Clare, Jonathan’s New York flatmate. Orange-haired, sassy, strident, a jewellery designer in her late thirties, she’s ‘the kind of woman always fated to play second banana in Thirties comedies’. They are, in Jonathan’s words, half lovers. They share everything except a bed. Jonathan’s sexual needs are taken care of by a blushing and monosyllabic bartender called Erich, referred to derisively as Dr Feelgood. Clare has officially given up on men. But when Bobby moves into their flat she realizes there is one thing she wants that Jonathan can’t give her and that is a baby. After she seduces Bobby the balance of the trio is abruptly destabilized. But eventually, uneasily, it is reconfigured. And when Clare becomes pregnant they decide the three of them will leave New York and bring up the baby together, creating the kind of family they’ve always yearned for. That New York is somewhere you experience, as opposed to making it your permanent home, is wonderfully conveyed by the fact that Clare and Jonathan have furnished their flat by picking up other people’s discards off the sidewalk. When they decide to leave, they simply take all their furnishings downstairs. Immediately other people appear to bear them gleefully away. You leave New York with what you brought with you: your records and your books. But Clare has inheritance money due so they can make a proper home in an old house near Woodstock. Jonathan and Bobby successfully open the Home Café nearby. Baby Rebecca is born and adored. Finally the trio have created their own version of a family. Even Alice, widowed at 50, has begun a new life. She sets up a catering company and begins a passionate relationship with a younger man. For each of the four narrators, some kind of stability has been achieved. Except. The time is the 1980s. This is not a novel ‘about’ AIDS but it offers some of the best, most truthful and most poignant writing about that terrifying time. The first, ominous note is sounded when Jonathan tells us, laconically and completely out of the blue: ‘The day our friend Arthur went to hospital, I traded histories with Erich. I just want us to have an idea about the scope of each other’s past. And for almost an hour we called in all our stray business, the affairs both good and bad.’ They conclude that, in terms of risk, they are somewhere towards the middle of the spectrum. ‘We’d hoped vaguely to fall in love but hadn’t worried because we thought we had all the time in the world. And in the meantime we’d had sex. And with each new adventure I’d imagined the prim houses and barren days of Ohio falling further away.’ At this stage AIDS is something that’s happening to other people. It’s only when Dr Feelgood arrives for a country weekend that a chain of events is precipitated that will determine the story’s outcome. As Erich steps down from the train, Jonathan says: ‘I knew as soon as I saw him.’ Can their new, fragile family absorb this information – and eventually Erich himself, as his family have disowned him? Each time I reread this book I am reminded again of the lesson that grace, insight and kindness can be found in the most appalling circumstances. Perhaps Bobby, privately, sums it up best: ‘There is a beauty in the world, though it’s harsher than we ever expect it to be.’

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 79 © Frances Donnelly 2023

About the contributor

Frances Donnelly still lives in the Waveney valley in Suffolk and is profoundly grateful for her Covid vaccinations. She never got a rescue dog.