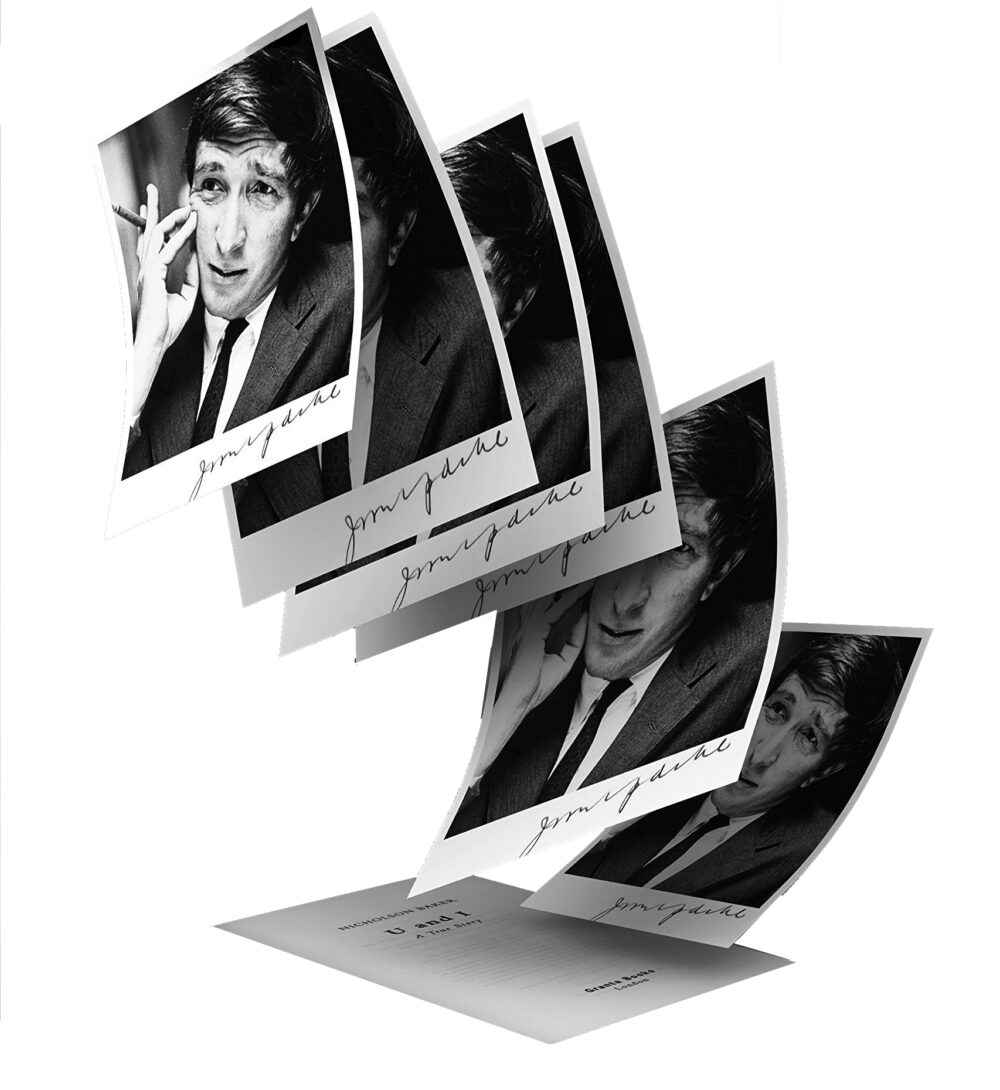

I hadn’t read much John Updike when I picked up Nicholson Baker’s book on him during lockdown; but then neither had Baker when he wrote the book. This is one of the novelties of U and I. Where most non-fiction strives for mastery of its subject, this little book pursues that ‘very spottiness of coverage [that] is, along with the wildly untenable generalizations that spring from it, one of the most important features of the thinking we do about living writers’. The result is a funny, profound meditation on what writers actually mean to readers as opposed to what academics tell us they should mean.

To say that Updike is a ‘living writer’ does date the book, of course. When U and I was published in 1991, however, there was no writer more alive than John Updike. He had just won his second Pulitzer Prize for the final novel in his ‘Rabbit’ tetralogy, he was still writing oodles of short stories and criticism for the New Yorker, and he had eighteen more years of equally absurd productivity ahead of him. Not that Baker could know this last part: indeed it is his very anxieties about his hero’s mortality that spur him to write about Updike. ‘To wait until a writer has died’, he reasons,

seemed to me . . . to go directly counter to one of the principal aims of the novel itself, which is to capture pieces of mental life as truly as possible, as they unfold, with all the surrounding forces of circumstance . . . The commemorative essay that pops up in some periodical, full of sad-clown sorrowfulness the year following the novelist’s death . . . is unworthy of the fine-tuned descriptive capacities of the practising novelist.

No. If he’s going to write about Updike, ‘it has to be done while he is al

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI hadn’t read much John Updike when I picked up Nicholson Baker’s book on him during lockdown; but then neither had Baker when he wrote the book. This is one of the novelties of U and I. Where most non-fiction strives for mastery of its subject, this little book pursues that ‘very spottiness of coverage [that] is, along with the wildly untenable generalizations that spring from it, one of the most important features of the thinking we do about living writers’. The result is a funny, profound meditation on what writers actually mean to readers as opposed to what academics tell us they should mean.

To say that Updike is a ‘living writer’ does date the book, of course. When U and I was published in 1991, however, there was no writer more alive than John Updike. He had just won his second Pulitzer Prize for the final novel in his ‘Rabbit’ tetralogy, he was still writing oodles of short stories and criticism for the New Yorker, and he had eighteen more years of equally absurd productivity ahead of him. Not that Baker could know this last part: indeed it is his very anxieties about his hero’s mortality that spur him to write about Updike. ‘To wait until a writer has died’, he reasons,seemed to me . . . to go directly counter to one of the principal aims of the novel itself, which is to capture pieces of mental life as truly as possible, as they unfold, with all the surrounding forces of circumstance . . . The commemorative essay that pops up in some periodical, full of sad-clown sorrowfulness the year following the novelist’s death . . . is unworthy of the fine-tuned descriptive capacities of the practising novelist.No. If he’s going to write about Updike, ‘it has to be done while he is alive’. Having ‘almost no idea what I was going to be able to say, only that I did have things to say’, Baker begins with some ground rules. The first is that he cannot read or reread a word more of Updike than he has already read, which, as I’ve mentioned, is surprisingly little: just eight of Updike’s then thirty-odd books in their entirety. To ‘supplement or renew my impressions with fresh draughts of Updike’ would mean ‘a multiplicity of examples would compete to illustrate a single point, in place of the one example that had made the point seem worth making in the first place’. The second is that any quotation must be done from memory. Only when the book is finished can Baker reopen Updike and check his recall (with the correct quotations put in parentheses after the incorrect). The results are fascinating. Though Baker’s recall is good, it is inevitably imperfect, sometimes wildly misremembering quotes, sometimes inventing them entirely. But accuracy is not the point. The point (which Baker proves beyond doubt) is that memory is always partial, and that to write about writers with all their works to hand is not actually true to how we think about them ninety-nine per cent of the time. We only ever have ‘an idea’ of a writer, not a full knowledge of them. This is most true of the living writer; their life and work being incomplete, we cannot but have a partial knowledge of them. And it is when we don’t have a full grasp of something, I suggest, that we resent it. Which brings me to one of the main joys of U and I: its envy. For as much as Baker admires that ‘serious, Prousto-Nabokovian, morally sensitive, National Book Award-winning prose style’ of his subject, he also hates him for it. One of his bitterest recollections is of

an amazing performance by Updike on Dick Cavett . . . where he spoke in swerving, rich, complex paragraphs of unhesitating intelligence that he finally allowed to glide to rest at the curb with a little downward swallowing smile of closure, as if he almost felt that he ought to apologize for his inability even to fake the need to grope for his expression.Another is of a 1980s documentary on Updike in which its subject talks eloquently to camera while doing some housework: ‘I was stunned to recognize that with Updike we were dealing with a man so naturally verbal that he could write his fucking memoirs on a ladder!’ Clive James was understating it, in my view, when he called this book ‘screamingly funny’. What’s funniest about Baker’s idea of Updike, though, is the sense he has of him as a friend. If only Updike knew how much they had in common – psoriasis, insomnia, an overly close relationship with their mothers – then they surely would be friends, Baker feels, before deciding that the amount of time he’s spent thinking about him makes them friends already. Hence his feelings of ‘hurt’ when he learns that ‘another youngish writer . . . living in the Boston area’ has been invited to play golf with Updike, not him; hence his conviction that he is the inspiration for the tall, pimply youth in Updike’s novel Roger’s Version (1986). Baker doesn’t seem quite so obsessed at the time of writing, thankfully, the book’s past tense giving its author an ironic distance from his younger self that is crucial to its comedy: ‘It may seem incredible, given how little I had published and how bad it was, that I could have even idly theorized as to why Updike wasn’t making an effort to seek me out, but I did.’ Were he still theorizing such things, the book would just have been creepy. As it is, U and I has given me as much pleasure on the second reading as it did on my first three years ago. Of course, if I really admired the book, I should probably have kept it closed and written this piece from memory, but then that would have been to deny myself the delights of Baker’s prose, which, despite its author’s inferiority complex, is just as baroque and brilliant as Updike’s. It would also have denied me some much-needed solidarity. For in the years since Baker first impressed on me the genius of John Updike, I too have seen the light and become something of an Updike obsessive myself; practically every other book I read has his name on it. And that’s a lonely thing to be when you’re 25 years old and Updike is as out of fashion as he currently is. What I’ve been in need of is a friend who understands; understands what it’s like to be addicted to a writer so prolific that there is an almost limitless supply of him. In Nicholson Baker I think I’ve found that friend.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 79 © George Cochrane 2023

About the contributor

George Cochrane is a writer and editor from remotest Northumberland. He now lives and works in London, where the air isn’t quite so clear.