In 1994, Hilary Mantel joined the Council of the Royal Society of Literature, where I was working as Secretary. She was in her mid-forties, and her sinister and hilarious fourth novel, Fludd, had been a big hit with our President, Roy Jenkins. Her fellow Council members warmed to her immediately. Matronly, but always beautifully dressed, she combined clear thinking with a cracking sense of humour, frequently shaking with laughter at the RSL’s eccentricities. So it was always a disappointment when, ahead of meetings, a note in her bold, steady hand curled out of the fax machine: she was ill, she couldn’t come, she was sorry. What was the nature of this illness?

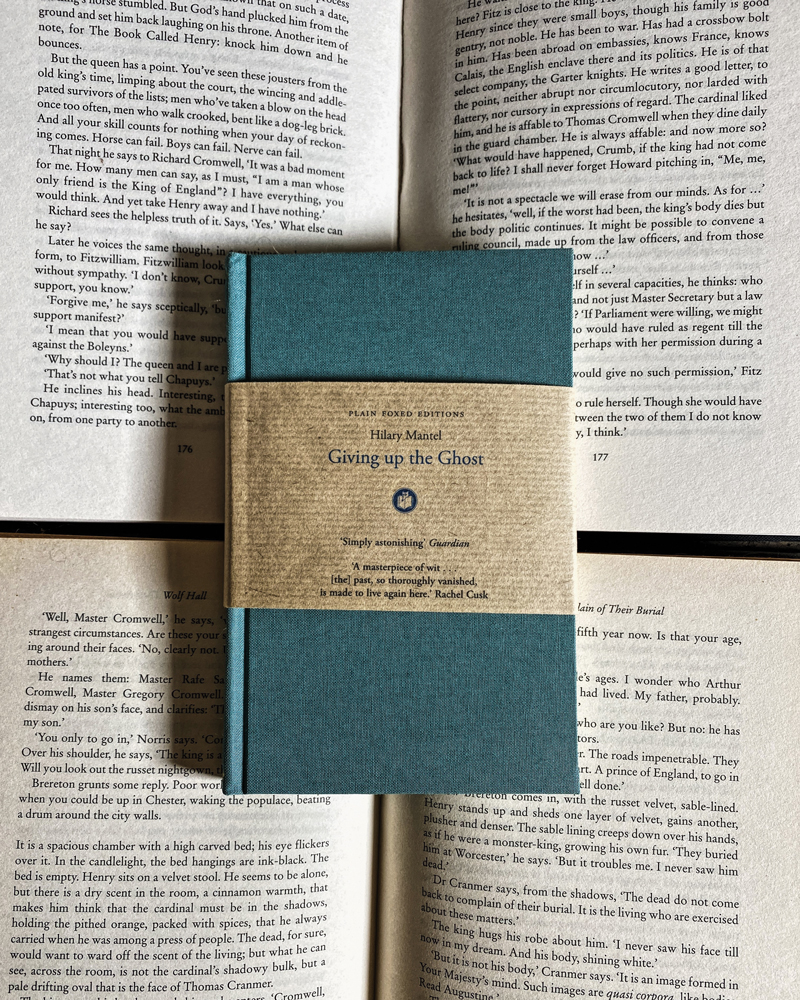

In 2003 her memoir Giving up the Ghost was published. I took it on holiday to Scotland, and read it in one great gulp. Then I understood. Asked what triggered the book, she admits that she never intended to write a memoir, and that it came about almost by accident. The sale of a weekend cottage in Norfolk moved her to write about the death of her stepfather, and from there ‘the whole story of my life began to unravel’. It is a story that crepitates with ghosts. She lays down provisions for them, stocking her larder with more food than she and her husband could ever eat, cramming her freezer with meat and her airing cupboard with spare linen. Some of the ghosts have names. Within the first few pages we are introduced to her dead stepfather, Jack, who manifests himself as a ‘flickering on the staircase’. Then there is the daughter she never had, Catriona, who is gifted at all sorts of things Hilary is not – driving, dealing with money, making curtains. Mostly, though, these ‘wraiths and phantoms’, which she believes flap around us all, can’t be precisely identified. They creep under carpets and into the fabric of curtains, lurk in wardrobes and under drawer linings. They represent versions of ourselves that might have been. ‘When the midwife says, “It’s a boy”, where does the girl go? When you think you’re pregnant and you’re not, what happens to the child that has already formed in your mind?’

Mantel has suffered more might-have-beens than most; but her childhood begins happily enough. Born into a working-class Catholic family near Manchester in 1952, she was for some years an adored only child ‒ ‘Our ’Ilary’ (‘my family have named me aspirationally, but aspiration doesn’t stretch to the “H”’). She is brilliant at capturing a child’s semi-understanding, and her early memories are pin-sharp. She sits in her pram, the trees overhead making ‘a noise of urgent conversation too quick to catch’. She climbs on to the knee of her tall, thin, intelligent-looking father, Henry Thompson, ‘helping’ him with the crossword by holding his pen, clicking the ballpoint in and out ‘so it won’t go effete and lazy between clues’. She likes to be close to people who are thinking – to enter the field of their concentration. While her father reads the racing pages, she imagines the horses: ‘I picture them strenuously’.

She falls in love with certain words: ‘scorn’, ‘bastion’, ‘citadel’, ‘vaunt’ and ‘joust’. She dreams of becoming a Knight of the Round Table, and believes that when she is 4 she will turn into a boy. Meantime she is ‘fat and happy’, her composure only occasionally shaken. One day she eats a green sweet from a cheap selection called Weekend, and becomes convinced that while putting it in her mouth she has breathed in a housefly. ‘There is a rasping, tickling sensation deep in my throat, which I think is the fly rubbing its hands together.’ The fear of death stirs in her chest ‘like a stewpot lazily bubbling’. She wonders whether to tell her parents she is dying.

School comes as a shock. None of the other girls seems interested in her bag of grey plastic knights or her knowledge of chivalric epi-grams. Mantel, meanwhile, cannot understand their eagerness for a game called ‘water’, which consists in floating plastic ducks to and fro across a basin. Nor can she comprehend the absurd questions posed by the teacher, Mrs Simpson: ‘Do you want me to hit you with this ruler?’ The only possible response to such inanity is silence. ‘“Hilary’s crying again”’ the other children chant – and no wonder. One day a nun, Mother Malachy, hits her so hard on the side of her head that she is propelled across the room, her head spun round on the stalk of her neck.

Before Hilary moves on to senior school – the Convent of the Nativity, where she becomes head girl – life at home has undergone a seismic change. One afternoon a man called Jack Mantel comes for his tea, and never leaves. In sharp contrast to her father, Jack is a rowdy presence, keen on weightlifting and singing. Quiet Henry remains in the house, moving into a single room. It is as if he is melting into the walls. Her mother stops going out. Hilary, eaves-dropping on adult conversation, tries to get some purchase on what is going on. She feels responsible for her father’s misery – there is something in her ‘beyond remedy and beyond redemption’. It is ‘the worst time in my life’.

‘Work out what it is you want to say,’ Mantel counsels novice writers, ‘and say it in the most direct and vigorous way you can.’ But even for somebody of her astonishing talents, some things are almost unsayable. One afternoon, playing in the back yard, her sight is drawn to something some fifty yards away, among coarse grass, weeds and bracken. She can’t exactly see anything, but she is aware of a disturbance of the air. She senses ‘a lazy buzzing swirl, like flies; but it is not flies’. Though there is nothing to see, to smell or to hear, she can intuit, at the limits of her senses, the dimensions of ‘the creature’. It is roughly the height of a two-year-old; it is a foot or fifteen inches deep. Something intangible has come for her – ‘some form-less borderless evil, that came to try to make me despair’. She is left shaking, ‘rinsed by nausea’.

It is tempting to see this Lord of the Flies moment, which knocks for six Hilary’s already shaky belief in an omnipotent God, as a manifestation of all that was wrong at home. When Hilary’s mother and Jack moved house, her father stayed behind. He was never mentioned again ‘except by me to me’. They never met again. But his absence did not bring happiness or peace. Everything Hilary did seemed to enrage Jack: ‘I was in trouble for being a girl, for being thirteen, for being fourteen. All my behaviour seemed to anger him, just by the fact of being behaviour: but silences, absences, were also a provocation to him.’ She skates over her teenage years in just a couple of pages, but there are hints of strain, and even violence. ‘There was tension in the air of our house, like the unbreathing stillness between the lightning and the thunder.’

What do you do when your family falls apart? Mantel’s instinct was to glue herself into a new unit. By the time she was 20 she was married to a geologist, Gerald McEwan, whom she was to divorce and remarry before she was 30. She was a student at the LSE, planning to become a lawyer and a politician. But by then there were intimations of a new kind of agony. Most people’s illnesses are as dull as holiday snaps, but Mantel’s descriptions of her symptoms have a gruesome fascination. From time to time something seemed to flip over and claw at her ‘as if I were a woman in a folk tale, pregnant with a demon’. Pain wandered about her body, ‘nibbling here, stabbing there, flitting every time I tried to put my finger on it’. The doctors dismissed her as an over-intense, over-ambitious girl, dosed her up with Valium and sent her packing. It was eight years before they accepted Mantel’s self-diagnosis of endometriosis, a condition in which the cells lining the womb grow in other parts of the body, bleeding monthly and binding the internal organs together.

The diagnosis meant an immediate hysterectomy, and the onset of the menopause. ‘I was twenty-seven and an old woman, all at once.’ In response to hormone treatment she began to balloon. From a seven-and-a-half stone slip of a thing she swelled outward, gathering fat in ‘places you never thought of’. By the age of 22 she had realized she would never have the stamina to become a lawyer or a politician, and had made a conscious decision to become a writer instead. By the time she hit 50, though still frequently unwell, she had eight novels under her belt.

Even as a successful writer of fiction Hilary Mantel felt for a long time unable to write about herself. Her life had been written by others – parents, teachers, the child she once was, and her own unborn children ‘stretching out their ghost fingers to grab the pen’. All were reflecting back contradictory versions of her: a fat sylph, the mother of a ‘paper baby’, a chronically ill malingerer, a wife and not a wife, Mantel but really Thompson. Writing Giving up the Ghost is an attempt to ‘seize the copyright’, to take command of her memories, and so gain some distance from them. But as she reveals in a rapid-fire interview at the end of my battered paperback, it was originally intended as a purely private exercise, like her diaries, only to be read by others after her death. What made her change her mind she doesn’t say; we can only be grateful that she did. In a crowded field, this is perhaps the strangest, most shocking, warmest and wittiest memoir to have been published this millennium.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 53 © Maggie Fergusson 2017

This article also appeared as a preface to Slightly Foxed Edition No. 37: Hilary Mantel, Giving up the Ghost

About the contributor

Maggie Fergusson is Literary Advisor at the Royal Society of Literature, where she has worked since 1992. She has written prize-winning biographies of George Mackay Brown and Michael Morpurgo, and has since sworn to her daughter that she won’t write another book.