Books can be ill served by the company they keep. In my childhood home they were shelved in the only bookcase and consisted entirely of anthologies published as Reader’s Digest Condensed Books plus the several volumes of Churchill’s The Second World War. None was ever read or even consulted. They were just part of the furniture. Something as slight as Joshua Slocum’s Sailing Alone around the World was lost amongst them. ‘That was Dad’s favourite book,’ said my mother as we cleared the house after his death. I’d no idea he had a favourite book, and it was not till some years later that, hoping to understand him better, I began turning its pages.

It was New England, 1892. The canvas-covered hulk was still just about recognizable as a sailboat, albeit one that had seen better days. ‘Affectionately propped up in a field some distance from salt water’, she had last worked on the oyster beds of the Acushnet estuary but by 1892 had been sitting there, high and dry in her Massachusetts meadow outside Fairhaven, for seven years. A tow to the breaker’s yard in nearby New Bedford looked overdue. It was either that or rot.

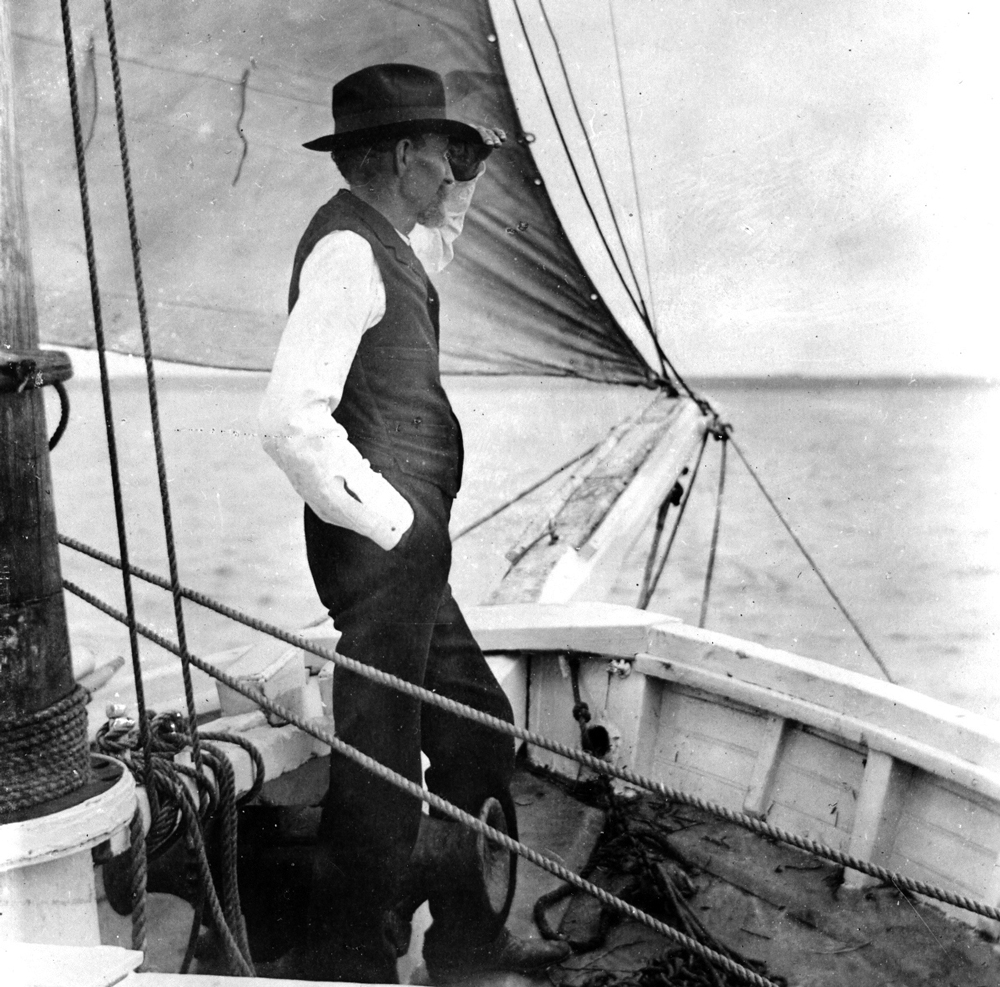

‘She wants some repairs,’ ventured the whaling captain who was disposing of her; her prospective buyer suspected the whaler of ‘having’, as he put it, ‘something of a joke on me’. But himself a shipwright and the skipper of numerous sailing vessels in an age that preferred steam, the buyer badly needed a command. Terms were agreed, proprietorship of the ‘very antiquated sloop called the Spray’ passed from Captain Eben Pierce to Captain Joshua Slocum, and with axe in hand a spry but balding Slocum bounded off into the woods, there to fell an oak for a new keel, cut timbers for a complete rebuild and so make ready for the voyage of the century.

Where others spied a hulk,

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inBooks can be ill served by the company they keep. In my childhood home they were shelved in the only bookcase and consisted entirely of anthologies published as Reader’s Digest Condensed Books plus the several volumes of Churchill’s The Second World War. None was ever read or even consulted. They were just part of the furniture. Something as slight as Joshua Slocum’s Sailing Alone around the World was lost amongst them. ‘That was Dad’s favourite book,’ said my mother as we cleared the house after his death. I’d no idea he had a favourite book, and it was not till some years later that, hoping to understand him better, I began turning its pages.

It was New England, 1892. The canvas-covered hulk was still just about recognizable as a sailboat, albeit one that had seen better days. ‘Affectionately propped up in a field some distance from salt water’, she had last worked on the oyster beds of the Acushnet estuary but by 1892 had been sitting there, high and dry in her Massachusetts meadow outside Fairhaven, for seven years. A tow to the breaker’s yard in nearby New Bedford looked overdue. It was either that or rot. ‘She wants some repairs,’ ventured the whaling captain who was disposing of her; her prospective buyer suspected the whaler of ‘having’, as he put it, ‘something of a joke on me’. But himself a shipwright and the skipper of numerous sailing vessels in an age that preferred steam, the buyer badly needed a command. Terms were agreed, proprietorship of the ‘very antiquated sloop called the Spray’ passed from Captain Eben Pierce to Captain Joshua Slocum, and with axe in hand a spry but balding Slocum bounded off into the woods, there to fell an oak for a new keel, cut timbers for a complete rebuild and so make ready for the voyage of the century. Where others spied a hulk, Slocum already saw a kindred spirit. The Spray would become the pride and joy of his later years, his faithful adjunct, his muse and literary device. More surprisingly, where others discerned just a boat, the captain envisioned a book. To a man of enquiring mind who could claim only two years of schooling, books had become as enticing as foreign lands. There was even a local precedent. Fifty years earlier the young Herman Melville had set sail from New Bedford as a deckhand on a whaler called the Acushnet. The voyage took Melville round the Horn into the South Pacific, providing inspiration for Typhoon and material for Moby-Dick. Slocum knew them both. He would even duplicate part of Melville’s itinerary before crossing the Pacific to complete what he called his ‘voyage round’, the first ever solo circumnavigation. But while Melville’s 360-ton Acushnet had been 100 feet long with two decks, three masts and a crew of twenty, the Spray was shaping up as a sloop of under 37 feet with a single mast, a net weight of 9 tons and a crew of one – Slocum himself. As well as noting Melville’s itinerary, Slocum had toyed with Melville’s career path. In the 1880s he had self-published his account of a calamitous voyage to Montevideo in command of a Baltimorebuilt clipper. The ship was the Aquidneck but the book appeared as The Voyage of the ‘Liberdade’, that being the name Slocum had given to a houseboat (‘half Cape Ann dory, half Japanese sampan’) which he and his family had constructed and then sailed home when the Aquidneck was wrecked off the South American coast. ‘This literary craft of mine’, began his account of that Swiss Family Robinson adventure, ‘goes out laden with the facts of the strange happenings on a home afloat.’ The words could have served as the preface to its more famous sequel, Sailing Alone around the World. Slocum already likened a blank page to the open ocean and his tender narrative to a craft in which to cross it. Throughout 1893 Slocum laboured with maul and adze above the Fairhaven shoreline. Cash being in short supply, he was obliged to take odd jobs including piloting an iron barge described as a ‘gun boat fitted with torpedo tubes’. This contraption, the antithesis of all a sail-loving mariner held most dear, had to be towed from New York to Bahia for delivery to the Brazilian navy, Slocum acting as ‘navigator in command’. It was an implausible assignment and prompted only the brief account which was penned of an evening in the Spray’s newly built cabin as the author rested from another day’s ‘sailorizing’ – now mostly planking and caulking. By 1894 the Spray was ready to return to her element. Nothing is recorded of the launch except that ‘she sat on the water like a swan’. Her master was rightly proud of her. ‘Put together as strongly as wood and iron could make her’, she yet ‘flew’ when Captain Pierce came for a trial sail. The rest of the year was spent fishing north to Boston and, by way of a farewell, cruising up the coast to Slocum’s Nova Scotia birthplace. Meanwhile he bombarded New York’s publishers. ‘My mind is deffinately fixed on one thing and that is to go round –’ he told the man acting as his agent, ‘to go with care and judgement and speak of what I see.’ Others could correct his spelling. What Slocum wanted was a serialization deal with a major journal, plus an advance. Both eventually materialized. At the port of Gloucester he took on potatoes, coffee and dried cod but for reading material he relied on his publishing contacts. His later editor records the titles that arrived in one of several boxloads: Darwin’s The Descent of Man and The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, Macaulay’s History of England and Trevelyan’s Life of Macaulay, Irving’s Life of Columbus, Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Twain’s Life on the Mississippi, ‘one or more titles by Robert Louis Stevenson’, a set of Shakespeare, and in ‘the poet’s corner’, as he called it, works of Lamb, Moore, Burns, Tennyson and Longfellow. The Spray’s library outweighed the potatoes. If nothing else, the captain, should he return, would be uncommonly well read. By 24 April 1895 he was ready. At noon the Spray weighed anchor and was waved off from the Boston waterfront.A thrilling pulse beat high in me. My step was light on deck in the crisp air. I felt there could be no turning back, and that I was engaging in an adventure the meaning of which I thoroughly understood. I had taken little advice from anyone, for I had a right to my own opinions in matters pertaining to the sea.The confidence was born of his forty years before the mast, many of them spent boatbuilding in the Philippines and ferrying exotic cargoes in the Far East. By one calculation Slocum had already been round the world five times. His knowledge of oceanography was extensive and his ability to read the winds and currents probably unsurpassed. He disdained instrumentation. For a chronometer he had a tin clock, which soon lost its minute-hand and required an occasional ‘boiling’. A lead was used to measure depths and a towed log to measure distances travelled. Bearings depended on a compass and meridian observations. At night he hung a lantern from the masthead and, below deck, lit a two-burner lamp for reading by. ‘By some small contriving’, the lamp also served as a stove. The Spray was excelling herself. Despite fog and storms, she covered the first 1,200 miles in ten days. Her captain’s ‘acute pain of solitude’ eased when the Azores yielded fresh fruit, only to be succeeded by greater pain from accompanying plums with goat’s cheese. For two days Slocum lay groaning on the cabin floor. He must have been reading Washington Irving’s Columbus, for it was one of Columbus’s pilots who materialized at the Spray’s helm and sailed her through the impending gale. The hallucination vanished as he recovered. ‘To my astonishment the Spray was still heading as I had left her. Columbus himself could not have held her more exactly on course.’ He ditched the plums and headed for Gibraltar. The plan was to continue east through the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal but the ill repute of the Barbary pirates prompted an about-turn. Pursued by a rakish felucca, he scuttled back into the Atlantic and made for Brazil. September brought sightings of the Canary and Cape Verde islands. The Spray was making the most of the trade winds. An over-friendly turtle improved his diet; flying fish obligingly flopped on deck, one slithering down the hatch straight into the pan. On 5 October anchor was cast in Pernambuco harbour; ‘forty days from Gibraltar, and all well on board . . . I was never in better trim . . . and eager for the more perilous experience of rounding the Horn.’ The Horn obliged. Instead of rounding the Cape, he tackled the Magellan Strait between the mainland and Tierra del Fuego – twice in fact. Battling repeated storms through a maze of islands, the Spray entered the Pacific only to be driven south towards what he supposed were the Falkland Islands. It was actually more of Tierra del Fuego. He turned north again and repeated his passage through the strait. Marauding Fuegians were kept at bay by strewing the deck with carpet tacks. On stepping aboard, the raiders ‘howled like a pack of hounds. I had hardly use for a gun.’ Two months after first braving the strait, and a year after leaving Boston, he was again alone in open water. The Pacific would be crossed by island-hopping in what reads like a literary pilgrimage. A first landfall was made on Juan Fernandez where Alexander Selkirk, the inspiration for Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, had been marooned in the early 1700s. The island now had a population of forty-five. Slocum regaled them with coffee and doughnuts from the Spray’s galley and visited the castaway’s cave. He so liked the island he couldn’t understand why Selkirk ever left it. After a seventy-two-day crossing – ‘a long time to be at sea alone’ – it was a similar story in Samoa. Stevenson had died at Vailima, his island home, just as Slocum was completing the rebuild of the Spray in Fairhaven. But Fanny, the author’s American wife, was still there, as were her son and daughter-in-law. All three piled into the Spray’s green dinghy (actually a customized dory in which Slocum did his washing) while Fanny sang ‘The Owl and the Pussy-cat’. As valedictory she presented the Spray with new spars and the captain with ‘a great directory of the Indian Ocean’ belonging to her husband. Australia marked the halfway point. Slocum knew it well; it was where he had met his first wife. The rest of 1896 was spent in Australian waters as was much of 1897. Unlike later solo circumnavigators he was in no hurry. He was fêted in Sydney and Melbourne, explored Tasmania, was nearly wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef and hit on a new source of income: visitors were charged for a tour of the Spray and public engagements were welcomed. Having read his way round half the world he would lecture his way round the other half. In Sailing Alone the homeward voyage runs to just forty pages. In actuality it took nearly a year with landfalls and lectures in the Cocos islands, Mauritius, Durban and Cape Town (where he failed to impress the explorer H. M. Stanley). The voyage was not without alarms; ‘but it was to me like reading a book and more interesting as I turned the pages over’. Published in 1900, Sailing Alone proved an instant success and has seldom been out of print. Nine years later the Spray and her master disappeared off the Massachusetts coast and were never seen again.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 79 © John Keay 2023

About the contributor

John Keay’s Himalaya: Exploring the Roof of the World was published by Bloomsbury in 2022. He has never owned a boat, but his father was a master mariner.