Thirty-nine years ago I came to work at Heywood Hill’s bookshop in Curzon Street. Between school and Cambridge, I had worked for three months at Heffers, where Mr Reuben Heffer had cannily put me in the Science Department. It was the only part of the shop where I wouldn’t read the stock. This could hardly be called a preparation for the sophisticated carriage trade in the West End, and I had little inkling of what would be expected of me. At my interview with Handasyde Buchanan, Heywood’s long-term partner and my future boss, it appeared that he considered himself the doyen of London booksellers and that he was pleased that, like him, I had had a Classical education.

Heywood Hill himself was going to retire from full-time work in the week before I arrived. For the next year he came in for two days a week but stayed largely in the basement where he banged away on his ancient typewriter and looked after any customers for prints, botanical and architectural. I was not encouraged to fraternize with him.

Handy opened the shop at 8.30 a.m. He didn’t expect customers for half an hour but he liked to arrive early – it was easier to find a taxi from Earls Court at that hour – and to wait for the post. Much importance was attached to his opening the letters. He divided them into those that were handwritten, generally orders for books, and the typed envelopes that contained publishers’ bills. Our own bills were handwritten – a tradition we kept until a couple of years ago when our accounts were finally computerized – and customers’ cheques came back to us in the same style, sometimes accompanied by a chatty letter. If I felt somewhat excluded from the magic circle of long-standing account customers, this was hardly surprising when there had been no change in the upstairs staff since 1946: Mollie Buchanan, Handy’s wife, had done the accounts since 1943 and Liz Forbes had dealt with the orders for new books for almost as long.

If I was going to be of any use when the Christmas rush started, I would have to learn fast. Sitting at a desk in the front of the shop, opposite what used to be the front door, I needed to recognize as many custom

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThirty-nine years ago I came to work at Heywood Hill’s bookshop in Curzon Street. Between school and Cambridge, I had worked for three months at Heffers, where Mr Reuben Heffer had cannily put me in the Science Department. It was the only part of the shop where I wouldn’t read the stock. This could hardly be called a preparation for the sophisticated carriage trade in the West End, and I had little inkling of what would be expected of me. At my interview with Handasyde Buchanan, Heywood’s long-term partner and my future boss, it appeared that he considered himself the doyen of London booksellers and that he was pleased that, like him, I had had a Classical education.

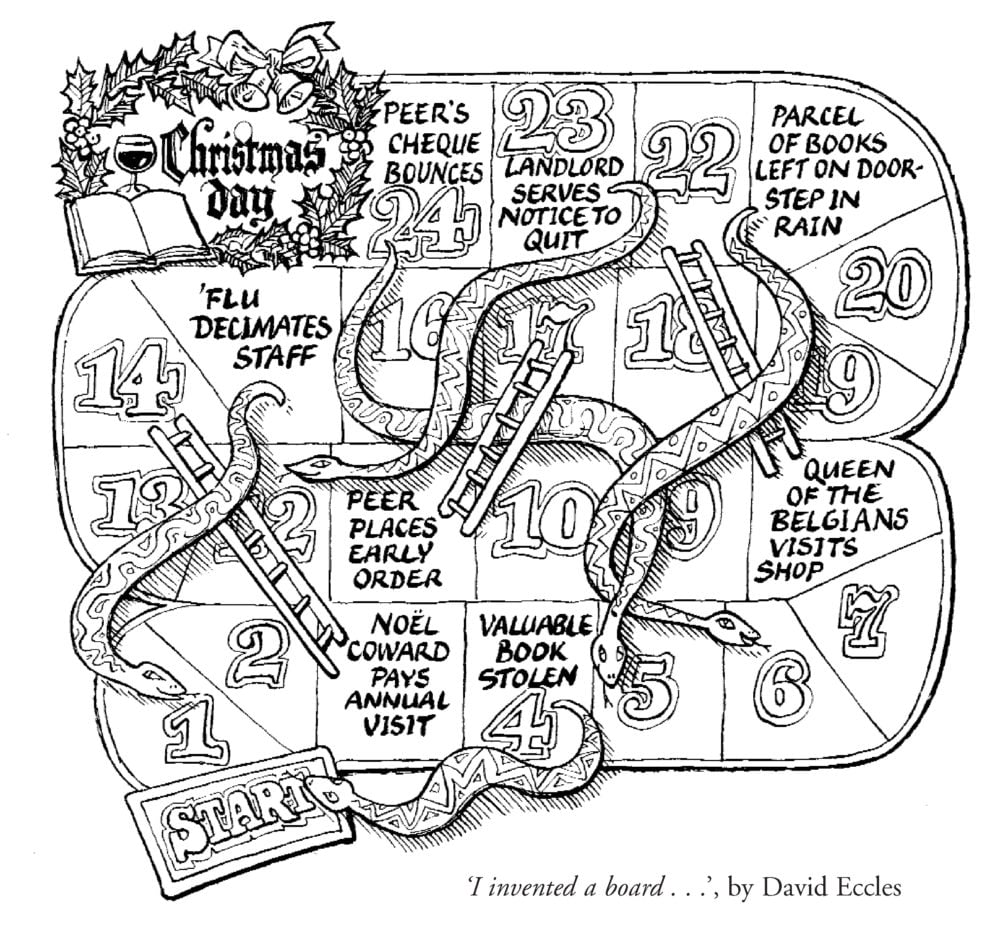

Heywood Hill himself was going to retire from full-time work in the week before I arrived. For the next year he came in for two days a week but stayed largely in the basement where he banged away on his ancient typewriter and looked after any customers for prints, botanical and architectural. I was not encouraged to fraternize with him. Handy opened the shop at 8.30 a.m. He didn’t expect customers for half an hour but he liked to arrive early – it was easier to find a taxi from Earls Court at that hour – and to wait for the post. Much importance was attached to his opening the letters. He divided them into those that were handwritten, generally orders for books, and the typed envelopes that contained publishers’ bills. Our own bills were handwritten – a tradition we kept until a couple of years ago when our accounts were finally computerized – and customers’ cheques came back to us in the same style, sometimes accompanied by a chatty letter. If I felt somewhat excluded from the magic circle of long-standing account customers, this was hardly surprising when there had been no change in the upstairs staff since 1946: Mollie Buchanan, Handy’s wife, had done the accounts since 1943 and Liz Forbes had dealt with the orders for new books for almost as long. If I was going to be of any use when the Christmas rush started, I would have to learn fast. Sitting at a desk in the front of the shop, opposite what used to be the front door, I needed to recognize as many customers as possible and memorize what they liked to read. Because I was inclined to literary biography and had read some Henry James, Handy’s literary bête noire, I was expected to take on Heywood’s customers. Our second-hand stock specialized in Victoriana and illustrated children’s books, in neither of which Handy took great interest: he himself was an expert on natural history books. He taught me the essential rudiments but, as I have explained to later recruits to bookselling, there are no guides or handbooks to the second-hand trade. You just have to buy and sell and learn from your mistakes. I also had to distinguish between regular customers and the large number of highly respectable publishers’ reps – Mr Prince from Hamish Hamilton, Mr Waite from Heinemann, Mr Church from John Murray, and so on (after about ten years I got to know their Christian names, but at this stage they were plain Mr). They arrived with heavy attaché cases loaded down by finished copies of books that would be published three weeks later. Handy insisted on taking all the decisions on the number of copies we wanted but he was given advice by Liz Forbes on fiction, particularly thrillers. He had strong views on a wide variety of subjects and our stock reflected many of his prejudices: theatre and the visual arts were of minor interest, literary life, especially Bloomsbury, particularly suspect. Once he’d decided on a winner, like a Duckworth reprint of Belloc’s Modern Traveller or Elizabeth Longford’s two-volume biography of Wellington, he would press a copy on all unsuspecting customers. He was a natural salesman and, with his Old Rugbeian tie (‘I have 36 at home’) and thick National Health spectacles, a self-invented English eccentric. Shop life varied from day to day. If I picked up the telephone, I was as likely to be asked for the new Osbert Lancaster cartoon book or the latest Agatha Christie as to be consulted on a seventeenth-century book on bird-cages or etiquette. Ten years later, a friend came for the pre-Christmas period to learn the essentials of bookselling before starting his own business in Brackley. He had previously worked for Blue Circle Cement, and the change was traumatic. ‘In my previous office,’ he said, ‘I was given five tasks to do each day and I fitted them in as conveniently as possible. Here you want me to do five jobs every half hour and each following half-hour will be different.’ So it was in 1965 except that I was a good deal younger than this friend, and there were no written Rules of the Game. No wonder that, strictly for my own amusement, I invented a board of Heywood Hill’s Snakes and Ladders. Our many American customers liked to be told about the highlights of the Christmas season in good time. Parcels had to leave London by the first week in November if they were to reach their destinations before Christmas (sea mail took three weeks to the East Coast, four to the West Coast). We needed to know which London bestsellers would not be available in New York for at least another six months so that we could reassure someone like Evangeline Bruce, the wife of the American ambassador, that her husband was unlikely to be given Alistair Horne’s Fall of Paris by anyone in the States. We were also expected to know what a regular customer had already bought; Lady Glendevon, the daughter of Somerset Maugham, wanted to be sure that her choice of present for her friend Mrs Paul Mellon wouldn’t be duplicated. There were no Christmas catalogues published for the general trade and, of course, no wholesalers like Bertrams to guide the independent bookseller. Every morning we ordered from a variety of publishers’ trade counters, John Murray in Clerkenwell, Oxford University Press in Neasden, Collins in Glasgow or Longmans in Harlow. Then there were W.B.R in Willesden, distributors for Weidenfeld & Nicolson, and Book Centre in Southport, unionized and famous for its self-inflicted problems. We gave orders over the phone (‘Kipling,’ a voice would say in Basingstoke, ‘how do you spell that?’), and we needed to exercise considerable patience. Each warehouse promised delivery in so many days: Murray and Heinemann the following day, Collins in five days, Book Centre somewhere between a week and ten days. To obtain Penguins we had to compile an order for 30 books, and it might take us a week or two before we had enough to qualify. In the three weeks before Christmas the reps would be given car stock and would hope to improve on the service from trade centres. If this sounds time-consuming and complicated, it was nothing to the chaos that resulted from a recommendation in the Sunday Times Best Books of the Year. In September a customer had brought back from holiday a quarto paperback called Lear in Corfu, published by a travel agency on the island. We had ordered ten copies, and, at 25 shillings, they had been a success. The paper then mentioned us as the only suppliers of this ‘charming gift’, though they failed to give us advance warning. It was already 8 December. We had no telephone number for the travel agency in Corfu and had previously ordered copies by postcard. Large numbers of customers now began to ask for copies and we had to explain apologetically that we were unlikely to get delivery until well into January. Heywood had referred to the Christmas season as Gethsemane, with some justification. After his retirement in 1966 he told Nancy Mitford that he loved his retired life, that anything would be better than Gethsemane; if that was a familiar allusion to the New Testament, I was inclined to speak of trench warfare. With so few of us to face the music, we were both stretched and stressed. Social life had to be shelved and Christmas parties postponed until we had finally closed. We were open until 5 p.m. on Christmas Eve and I reached my parents’ house that evening in time for supper. After Boxing Day, I slept for 48 hours without a break.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 4 © John Saumarez Smith 2004

About the contributor

John Saumarez Smith has just edited the letters between Nancy Mitford and Heywood Hill. They revived many memories of his early days of bookselling.