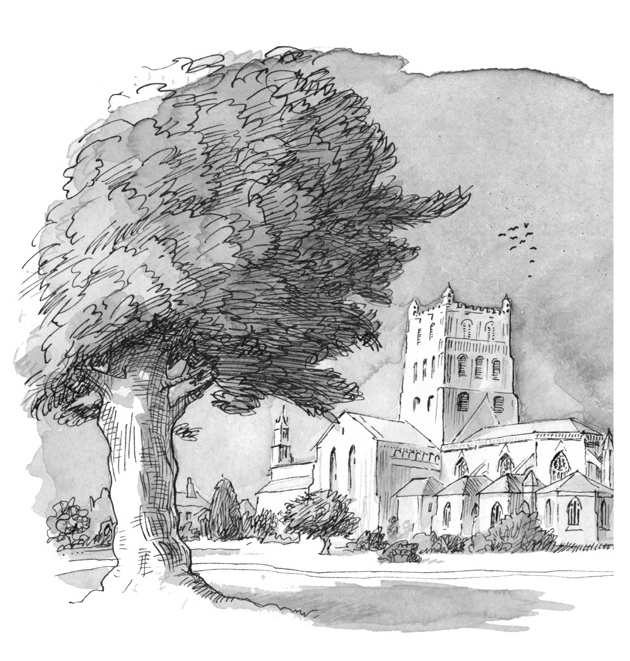

At the time of writing, the town of Tewkesbury, in the north-west corner of Gloucestershire, has been cut off by the flooding of its four rivers: the Severn and Avon, at whose confluence it stands, and smaller streams named Swilgate and Carrant. Only the great Norman abbey, with its necklace of Gothic chapels, rises above the turbid brown tides that surge across the meadows. England is more richly watered than elsewhere in northern Europe, but now this very same element seems thoroughly hostile to the humans who planted the woods, ploughed the fields and staked the hedges enclosing them.

This sense of nature reasserting herself would have appealed to Tewkesbury’s greatest writer. I’m not talking about Dinah Maria Mulock, author, as Mrs Craik, of the once-popular John Halifax Gentleman (1856), or of Henry Yorke, scion of the local gentry, who wrote under the pen-name Henry Green. The talent I’d like to celebrate is less blatantly moralizing than Craik’s and not quite so aesthetically self-conscious as Green’s. A Tewkesburian middle ground between them belongs firmly to John Moore, whose best books are rooted, as theirs for whatever reason are not, in the changing rural scene around him. Moore’s passionate absorption is understandable. It’s hard not to see this area of England, where the three counties of Worcestershire, Herefordshire and Gloucestershire converge, as enchanted ground, the more so for me since I grew up there. My remembered hills are the pink granite Malverns and my land of lost content is that rolling terrain of pastures, cornlands and orchards stretching eastwards to Bredon and south to the Severn estuary.

Moore was, in whatever sense, all over this country. His family’s auctioneering business, based in Tewkesbury, sold the livestock, har- vests and machinery of local farmers. He knew about heifers, steers and store cattle, the difference between a wether and a tup, and just how a Fordson Major compared with a Ma

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inAt the time of writing, the town of Tewkesbury, in the north-west corner of Gloucestershire, has been cut off by the flooding of its four rivers: the Severn and Avon, at whose confluence it stands, and smaller streams named Swilgate and Carrant. Only the great Norman abbey, with its necklace of Gothic chapels, rises above the turbid brown tides that surge across the meadows. England is more richly watered than elsewhere in northern Europe, but now this very same element seems thoroughly hostile to the humans who planted the woods, ploughed the fields and staked the hedges enclosing them.

This sense of nature reasserting herself would have appealed to Tewkesbury’s greatest writer. I’m not talking about Dinah Maria Mulock, author, as Mrs Craik, of the once-popular John Halifax Gentleman (1856), or of Henry Yorke, scion of the local gentry, who wrote under the pen-name Henry Green. The talent I’d like to celebrate is less blatantly moralizing than Craik’s and not quite so aesthetically self-conscious as Green’s. A Tewkesburian middle ground between them belongs firmly to John Moore, whose best books are rooted, as theirs for whatever reason are not, in the changing rural scene around him. Moore’s passionate absorption is understandable. It’s hard not to see this area of England, where the three counties of Worcestershire, Herefordshire and Gloucestershire converge, as enchanted ground, the more so for me since I grew up there. My remembered hills are the pink granite Malverns and my land of lost content is that rolling terrain of pastures, cornlands and orchards stretching eastwards to Bredon and south to the Severn estuary. Moore was, in whatever sense, all over this country. His family’s auctioneering business, based in Tewkesbury, sold the livestock, har- vests and machinery of local farmers. He knew about heifers, steers and store cattle, the difference between a wether and a tup, and just how a Fordson Major compared with a Massey Harris when trundling a combine. He went shooting, fished the streams and, as his friends recalled, maintained more than a nodding acquaintance with various poachers across the big estates. His amazing eye for detail in the habits of wild creatures, the rhythm of the seasons and the texture of the landscape made Moore a classic example of the ‘man who used to notice such things’ celebrated in Hardy’s poem ‘Afterwards’. A prolific writer on the English countryside, Moore never sentimentalized his subject, fully understanding what was pitiless, violent and unpredictable within it and familiar with the surly resentments, fatalism, ignorance and superstition darkening rural life. Sensitive to its poetic inspirations, like Edward Thomas whose work he helped to bring back into favour, Moore was just as close to Richard Jefferies, that pioneer rustic realist, in striking the perfect balance of fluency and detachment so as to give authority to his writing as a countryman. Moore’s energy in this cause was the more focused for his sense of the rapid, often brutal changes taking place in the agricultural scene around him. His particular patch of England may have seemed very much an Angleterre profonde of meadows, hedgerows, thatched cottages and mossy churchyards, but hostile forces were poised to undermine its traditional fabric. In his splendid Brensham trilogy, begun in 1946 (and recently reissued by Slightly Foxed), he had bid- den an elegantly crafted farewell to the Tewkesbury vale of his youth and to several of its more colourful characters. His last major work, however, The Waters under the Earth (1965), uses the novel form to engage more intensely with themes of survival, resistance and compromise in a world where, as the book’s most anguished protagonist declares at its opening, ‘Nothing’s going to be the same again, ever.’ It is the 1950s and we are once again in Moore country, at Doddington Manor, not far from Elmbury (Tewkesbury), where the Seldons have been squires since Domesday. Things are not quite what they were at the manor house. It has crooked chimneys, cracked roof tiles and rot both wet and dry in its beams and floors, fashioned from the great oaks in the park planted by Ferdinando (‘Ferdo’) Seldon’s ancestors. The oaks themselves are menaced now by the intrusion of a new road sweeping remorselessly across the river near the ancient ferry and chomping up two woods named Trafalgar and Waterloo. ‘Could the Powers that Be really do such things upon a man’s land nowadays?’ Ferdo wonders. ‘Of course they could, for that was the way the weather was, that was the way the tide was running.’ His wife Janet sees things altogether differently. In The Waters under the Earth she emerges as one of the most compelling figures for her refusal to make peace with the era in which she has the bad luck to live. Since this is a novel which painstakingly examines the nature of Englishness for good or ill, class forms a significant element in the story and Janet Seldon’s social prejudices and presumptions as ‘her ladyship’, the squire’s wife, are sustained with a doggedness that assumes an increasingly pathetic desperation. Moore neither condemns nor mocks her for this, choosing instead to use extracts from her diary, with its underlinings, words in capitals and schoolroom French, to provide an alternative thread throughout the narrative. Ferdo and Janet have one child, Susan, who is not the Country Life girls-in-pearls daughter such parents might wish for. ‘I’m frightened for you sometimes,’ says a friend, ‘I’ve got a feeling that you – attract the lightning, my dear.’ In this guise she makes a memorable heroine, courting accident yet always enduring its scars. When, at the Stow-on-the-Wold horse fair, evoked by the writer with anthropological gusto, Susan buys a ‘ribby, rakish’ mare named Nightshade, the beast perfectly matches her new owner, ‘cantering delightfully on the razor edge of fear’. A gift for staying metaphorically in the saddle is what Susan has inherited from her father. While Janet, in the pages of her diary, laments ‘the palmy days’ when the ‘whole county ORGANIZED for hunting’, Ferdo adopts a far more speculative and philosophical attitude to the encroaching present. He enjoys arguing with Susan’s friend Stephen Le Mesurier, the local Tory candidate in the forth-coming General Election, whose Conservatism is suspect to Janet because he is too clever by half, and that half happens to be Jewish. Equally Ferdo relishes a chance to spar with the boorish nouveau riche Colonel Daglingworth, whose local business interests are unlikely to be thwarted by qualms over heritage, tradition and wild nature. For Ferdo, a wartime naval officer, however, contrariness of all kinds needs to be met with equanimity, summarized in his mantra, ‘Pro bono publico, no bloody panico’. The Seldons will need such equanimity in spades when Fenton, the new gardener, arrives with his wife and five children. ‘We’ve no real reason to imagine he’s a Communist or anything of the kind,’ Ferdo assures a fretful Janet, but she requires a good deal more per- suasion after meeting Mrs Fenton, ‘one of those angular, waspish, red-haired, hygienic, purposive women with spectacles, who look intellectual even if they aren’t’. The truth is that the gardener’s wife, while being Lady Seldon’s polar opposite, is also her mirror image. Each woman, whatever their difference in status, matches the other in a tyrannical absence of vision or imagination. On one of its many levels, The Waters under the Earth is a worthy enough rival to E. M. Forster’s Howards End in asking ‘Who will inherit England?’ The Seldons and the Fentons may not be as sophisticated in their fashioning as the Schlegels and the Wilcoxes, but they are just as authentic and the underlying question remains the same. Moore’s plot is in any case staked out along the wider historical trajectory of post-war Britain. Susan’s first fiancé, her cousin Tony, heir to Ferdo’s baronetcy, is taken prisoner while serving in Korea, young Ben Fenton is called up to fight in the Suez affair, and a Coronation Day fête is a freezing non-event. The drama of surviving the muddle, bewilderment and despair threatening to overwhelm Doddington is heightened by Moore’s neat deployment of symbols. As Ferdo learns, eventually, to welcome the grey squirrels who have driven out their red cousins represented on his family escutcheon, he is listening, at the same time, to the motor- way engineers felling the great oaks in his park. Honey fungus, gross intruder, the woodland equivalent of Colonel Daglingworth, is spreading decay among the coppices even as the subterranean waters of the novel’s title are starting to flood the manor-house cellars. Stephen Le Mesurier sees the rising streams as emblematic of some- thing deeper, an ebb and flow in the currents of English perpetuity. ‘Powerful, ubiquitous, secret, they would burst out of confinement’, buoying up some and drowning others. Janet appears a destined casualty of this hidden tide. The novel brims with cleverly engineered episodes in which essential narrative strides dovetail with Moore’s appetite for scene-painting. Daglingworth’s pheasant shoot is one such, Susan’s triumphant point-to-point gallop on Nightshade is another, but best of them all, for its ominous terseness, is the Women’s Institute AGM at which Janet, having deluded herself that she will be president for life, is cruelly ousted by the wife of a local factory owner. That evening’s diary entry is among the bitterest. ‘Beasts!! BEASTS!!! Can hardly believe it after all these yrs. Know I wasn’t v. good, not my métier, but did my best and LOVED it (Why???) Why do I mind??? Could not easily say Despise myself S-pity most horrible.’ Deference swiftly fades among Elmbury shopkeepers, and teddy boys rough up Janet’s old hunter, while Susan’s own alter ego, Doddington’s maid Rosemary, becomes pregnant and is forced into a hasty marriage with her lowlife village boyfriend before running off to a job in Birmingham in return for servicing the lecherous Daglingworth. The world, as Susan and Ferdo come to understand, has to be reckoned with on its own highly ambiguous terms. Father and daughter are ready to negotiate, as neither Janet nor Mrs Fenton seems capable of doing. Stephen Le Mesurier, meanwhile, seeks a bromide in the poetry of Hopkins and Baudelaire to deaden the coarse, inexorable foot-stomp of progress across the Gloucestershire Arcadia. Watching Fenton stacking a bonfire, Egbert the handyman recalls a superstitious rhyme:Make a fire of elder tree, Death within the house shall be.Yet this very same death will also signal a kind of solution or release. John Moore has been accused of sentimentalizing the book’s ending, but this is to misunderstand his obvious intention in writing it. Yes, there is, thank goodness, a wonderful scatter, through its pages, of the author’s country lore – the colour of a beech tree bole, the song of a chiffchaff, ‘a sky that faded from primrose to a starling’s-egg blue’ – but this never muffles or clutters the narrative’s overall integrity. The modern demand for conclusions of unmitigated bleakness and misery now has its own musty banality. There’s enough anyway, at the close of The Waters under the Earth, to satisfy this kind of cliché. Doddington Manor will tumble down, damaged cousin Tony will inherit the estate, Ben Fenton’s Suez wound may yet turn septic and Susan’s baby by him may be stillborn. This is to miss the point entirely. What survives, in Moore’s England, is its atavistic capacity for shape-shifting and self-renewal, with a little help from Ferdo’s ‘Pro bono publico, no bloody panico’, Fenton’s bonfires and the occasional no-confidence vote at the WI.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 70 © Jonathan Keates 2021

About the contributor

Jonathan Keates grew up not far from Tewkesbury and his first published book, The Companion Guide to the Shakespeare Country, included chapters on many places familiar to John Moore.