If Sydney Smith’s idea of heaven was eating pâté de fois gras to the sound of trumpets, my own more mundane vision of bliss is undisturbed delving in the boxes of nineteenth-century broadsides and entertainment ephemera that are to be found in a few special collections. The occasional requirement to wear white cotton gloves adds an extra frisson of expectation but, contradicting the usual rules of desire, anticipation is seldom more satisfying than tangible access. The obligatory silence is sexy too, broken only by the alluringly low whisper of those who have spent years observing library rules. Boxes marked ‘miscellaneous’ invariably yield the best finds, for scarcity means there is rarely more than one item for each entertainment, and many defy categorization.

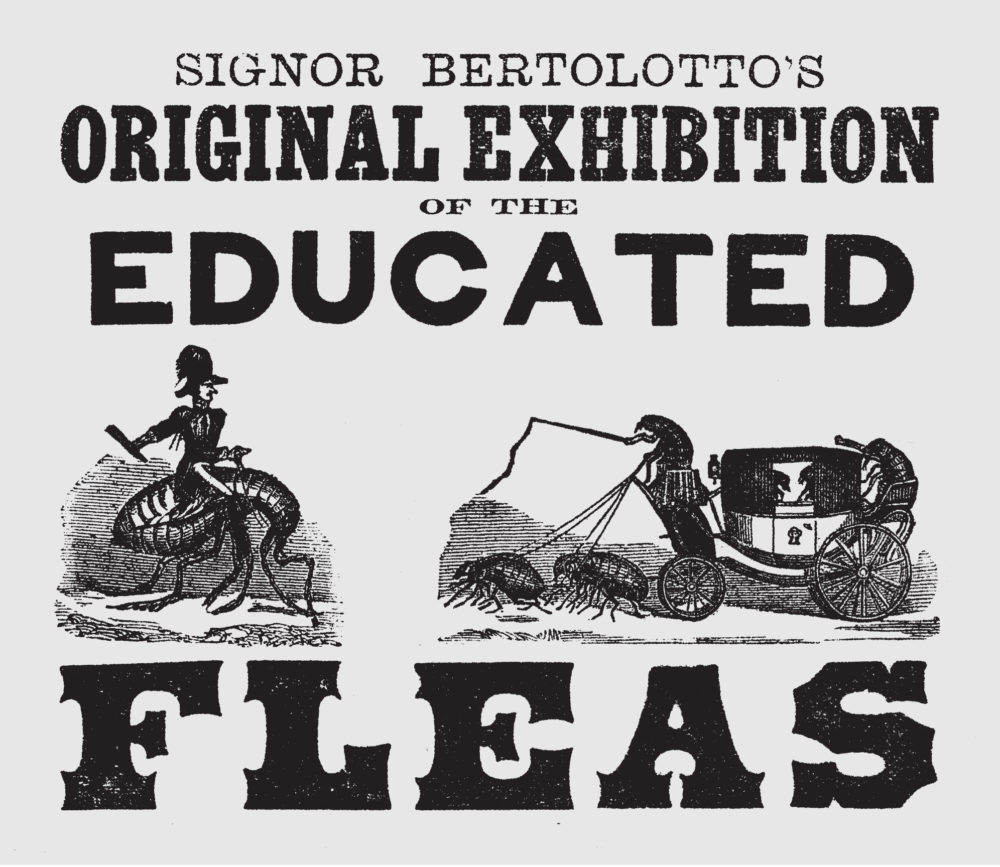

Here are some of my recent discoveries. An 1829 orange handbill for Signor Cappelli’s Learned Cats who turn the spit, strike an anvil, roast coffee and display ‘many other agreeable qualities’ every hour at 248 Regent Street. A charming engraving of the Whale Lounge – a ninety-foot skeleton of ‘a gigantic whale’ converted into an elegant pavilion that was the talk of the town when it opened at Charing Cross in 1831, inviting would-be Jonahs ‘to inspect and sit in the belly of the whale where twenty-four musicians perform a concert’ and where the chance to peruse a selection of natural history and a VIP visitors’ book was an extra draw. Finally, a poignant reminder that it was not always all right on the night, an 1836 handbill for a show at the Rosemary Branch tavern, Islington, announcing that ‘Madame Rossini who has now fortunately recovered from the accident she unfortunately met with on Monday night last will perform some wonderful evolutions on the tight rope accompanied by Mr Davis who will make a grand display of pyrotechnical art on her attaining the summit.’

While Time Out tempts us each week with all that London has to offer, the conventional cultural showcases are as nothing compared to the dazz

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIf Sydney Smith’s idea of heaven was eating pâté de fois gras to the sound of trumpets, my own more mundane vision of bliss is undisturbed delving in the boxes of nineteenth-century broadsides and entertainment ephemera that are to be found in a few special collections. The occasional requirement to wear white cotton gloves adds an extra frisson of expectation but, contradicting the usual rules of desire, anticipation is seldom more satisfying than tangible access. The obligatory silence is sexy too, broken only by the alluringly low whisper of those who have spent years observing library rules. Boxes marked ‘miscellaneous’ invariably yield the best finds, for scarcity means there is rarely more than one item for each entertainment, and many defy categorization.

Here are some of my recent discoveries. An 1829 orange handbill for Signor Cappelli’s Learned Cats who turn the spit, strike an anvil, roast coffee and display ‘many other agreeable qualities’ every hour at 248 Regent Street. A charming engraving of the Whale Lounge – a ninety-foot skeleton of ‘a gigantic whale’ converted into an elegant pavilion that was the talk of the town when it opened at Charing Cross in 1831, inviting would-be Jonahs ‘to inspect and sit in the belly of the whale where twenty-four musicians perform a concert’ and where the chance to peruse a selection of natural history and a VIP visitors’ book was an extra draw. Finally, a poignant reminder that it was not always all right on the night, an 1836 handbill for a show at the Rosemary Branch tavern, Islington, announcing that ‘Madame Rossini who has now fortunately recovered from the accident she unfortunately met with on Monday night last will perform some wonderful evolutions on the tight rope accompanied by Mr Davis who will make a grand display of pyrotechnical art on her attaining the summit.’ While Time Out tempts us each week with all that London has to offer, the conventional cultural showcases are as nothing compared to the dazzling variety of live entertainments that were on offer to Georgian and Victorian audiences. As purveyors of affordable thrills directed to a more respectable audience than the loud, louche scrum of the fairs, the itinerant show-people constitute a shadowy underclass whose tracks are faint on the historical record. A paper trail of precious publicity fragments is virtually all the evidence we have of the almost perpetual cavalcade of performers that passed through London and toured the provinces, setting up for a few days in assembly rooms, taverns and market places. For penetrating the anonymity of savants of every species, the troupes of funambulist birds and industrious fleas, the freaks and frauds who amazed and amused in equal measure, and for putting a woefully neglected aspect of social history within reach of a wider audience, we owe a considerable debt of gratitude to the American author and entertainment historian Ricky Jay. He has spent his life collecting entertainment ephemera spanning the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries, but his interest is not simply theoretical. He himself is an acclaimed sleight-of-hand magician. He has an entry in the Guinness Book of Records for throwing a playing card 190 feet at 90 miles per hour, and his signature turn is to throw a card into a watermelon rind. And if that is not enough to command respect, you know you should take him seriously when you learn that David Mamet has directed his stage shows. Discovering Jay’s writing, I was instantly aware of a kindred interest. Here was someone else for whom each tiny rusted paper clip, each missing corner and tear enhanced the wonder inherent in the survival of material which was only ever designed to be discarded after use – as dispensable and unwelcome in its day as the pizza delivery flyer. Pushed under doors, pressed into the palms of passers-by, these handbills and broadsides were normally printed on one side and usually measured no more than six by eight inches. With their times, dates and venues, encomia from the press and occasional boasts of royal patronage vastly at odds with the humility of their premises, they are an instant evocation of a vanished world, the past not as the ventriloquism of the historian but speaking for itself. Apart from the occasional woodblock, handbills are more a verbal than a visual medium, and a large part of their appeal lies in their language. Neologisms as hard to pronounce as to understand were designed to induce curiosity. Who could resist the chance to see the Heptaplasiesoptron – a sophisticated optical illusion producing spinning reflections of palm trees, fountains and serpents – or the Whimsiphuscion that featured on the programme of Mr Sugg, Professor of Internal Elocution. Some invitations lose nothing by their simplicity, for example the bill exhorting the public to take a look at the ‘Wonderful American Hen’, or the ‘Wonderful Remains of AN ENORMOUS HEAD . . . the complete bones of which were discovered in excavating a passage for the purpose of a railway’ and which was on show daily from 10 till 6 at the Cosmorama, 209 Regent Street, in 1840. Ricky Jay’s Learned Pigs and Fireproof Women is an enchantingly idiosyncratic overview of popular entertainments, including those of the title. It also exposes many of the scams on the circuit, my particular favourite being ‘the pig-faced lady’ who in various incarnations over the centuries duped the punters in the form of a bear with shaved head and gloved paws, its bulky body disguised under reams of dress material. Jay’s narrative is a reminder of how misguided it is to relegate these shows to the margins of serious enquiry, for many of them percolated through the mainstream consciousness of the day. In Regency London for instance, a particularly soignée swine-faced lady ‘of Manchester Square’ inspired a series of elegant engravings, and several less flattering satires by George Morland and George Cruikshank. Another porcine star was Toby the Sapient Pig, who could be seen at the Royal Promenade Rooms, Spring Gardens, every afternoon and evening. To prove his mind-reading prowess, ‘Any lady or gentleman may put Figures in a Box and this wonderful Pig will absolutely tell what number is made before the box is open.’ Toby was not only sapient, he was also a published pig (ghost writing was denied). The Life and Adventures of Toby the Sapient Pig: With Opinions of Men and Manners (London, 1817) was priced at one shilling – his enterprising owner had clearly identified another way of making bacon. A personal favourite of Jay’s is the German showman Matthew Buchinger (1674–1739). Known as the Little Man of Nuremberg, Buchinger was born without arms and legs and never grew to more than twenty-nine inches. He became renowned for his intricate penmanship and compositions formed with miniature writing, which he produced by manipulating the pen between the protuberances at his shoulders. (Several grace important fine art collections.) A coin-sized portrait would, on closer examination with a magnifying glass, reveal the curls of a subject’s hair to be perfectly legible lines of the Lord’s Prayer. His piety however was confined to paper, for he married seven times and was the father of fourteen children. Another performer who captured the public imagination was the Stone Eater. He packed in the crowds at Mr Hatch’s Trunkmaker, 404 Strand, with his daily display of ‘gnawing, crunching and reducing a range of pebbles which when swallowed may be heard to clink in his belly’. The Stone Eater inspired songs, satires and imitation in the form of stone-eating automata, and also a flesh-and-blood rival, ‘Siderophagus or the Eater of Iron’. Spectators were invited ‘to bring a bunch of keys, a bolt or a poker which he digests with as much ease as if they were gingerbread’. By contrast, as the Living Skeleton, Claude Seurat was famous for not eating at all, or so it seemed from his protruding bones and extreme emaciation. Refuting the idea that the Georgians’ enthusiasm for freak shows was universal and that to a man they were hardhearted voyeurs, Jay cites The Lancet which denounced the Living Skeleton as ‘one of the most impudent and disgusting attempts to make a profit of the public appetite for novelty’. But even more striking is Seurat’s own defence. Far from being exploited, he insisted that his exhibitors were funding his dreams of a happy retirement in his homeland, and saving him from ‘a profitless wandering life of self-exposure’. If Seurat left many cold, that was never the case with Chabert the Fire King who took the celebrity chef concept to a whole new level by making himself the prime ingredient of his recipe for entertainment by entering an oven in which joints of meat were simultaneously cooked. He enjoyed wide press coverage and was alluded to by several authors, including Charles Dickens. Marvels such as these process through the pages of Jay’s wonderful book and, though the brackets of my own enthusiasm close with the mid-nineteenth century, Jay’s interest extends to the twentieth. Along the way he features fin de siècle ‘fartomania’, including a female rival to the famous Frenchman Joseph Pujol, known as Le Pétomane. Under the stage name La Mère Alexandre, her pièce de résistance was a loud but odourless imitation of the bombardment of Port Arthur. Lest we should dismiss such entertainments as the cheap laughs of music hall, Jay identifies a long and distinguished tradition of musical farting in Japanese culture. As well as being a staple in the variety acts, or misemono, which blossomed during the Edo period, there are references to petomania in important fifteenth-century folk-tale scrolls and in a respected treatise, On Farting, by Hiraga Gennai, first published in 1777. Jay’s second book, Extraordinary Exhibitions, supplements rather than replicates the content of the first. Indeed, it is a superb companion, and cross-reference between the two is richly rewarding. Drawing on his own collection of broadsides, Jay provides an original pictorial chronology of publicity material for an immense variety of live shows from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. Even scrutinizing the small print is worthwhile, for it highlights the commercial flair of these cultural entrepreneurs. ‘Will attend private families at their own residences’ is a common footnote. Sidelines are in evidence too. The equestrian apiarist Daniel Wildman advertised ‘Fine Virgin Honey to be sold either in the combs or out; also his new invented hives either for the chamber or the garden and any quantity of bees from one stock to one Hundred’. (In the 1770s he took stunt riding to new levels of daring by introducing up to five swarms of bees in his act. While he stood on the saddle, the bees would form a blindfold over his face until, at his command, they would part to allow him to drink a glass of wine.) In my own research for a biography of Madame Tussaud (whose famous exhibition was for over twenty-five years a travelling show before she finally gave up the punishing itinerant lifestyle and settled in London at the age of 74), I found a wonderfully thought-provoking footnote on an 1804 handbill. ‘Ladies and Gentlemen may have their portraits taken in the most perfect imitation of Life; Models are also produced from persons deceased, with the most correct appearance of imitation.’ Jay’s books underline the fact that curiosity and the capacity for wonder are universal human traits. Indeed they are the scaffolding of popular culture. Even today, the freak show persists, albeit prerecorded and disguised as popular science. Just think of all those TV documentaries about conjoined twins and the most extreme manifestations of physical difference. Though the packaging has changed, our interest in the freakish remains undiminished.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 12 © Kate Dunn 2006

About the contributor

Kate Berridge has contributed to a variety of publications, including the Spectator, the Sunday Telegraph and Vogue, but she is far happier researching the nineteenth century than reporting the twenty-first. Having recently completed Waxing Mythical: The Life and Legend of Madame Tussaud, she is already pining for the stacks and plotting a reason to return.