‘Neither a borrower nor a lender be,’ my grandfather used to say gravely. His caution wasn’t about money. It was about books. Do not lend a book you will want back and do not borrow one you will be sorry to return. Sound advice. Not that I’ve kept to it. Some books I am willing to relinquish. That makes space on my heaving shelves. The loss of others I mourn.

I lent my copy of Barbara Hepworth’s A Pictorial Autobiography to an illustrator friend who, for reasons of distance and diaries, I rarely see. We had been talking about children and creativity and whether one must necessarily restrict the other: the easel, the laptop, the pram in the hall. I said she must read Hepworth and posted her my copy. It arrived. She thanked me. After that: nothing. Nothing for months and months and a year, and for months after that. I nursed a perverse and very British grievance. I couldn’t possibly ask for it back, because that would be rude. Instead, I did the proper and polite thing of raining resentment, curses and hellfire on her head every time my eye caught the gap in the bookcase.

As the second anniversary of the lending approached, I shrugged, shuffled the shelf and wrote the book off as a loss. Then, in the way of watched pots never boiling, the book came back with a hand-painted card and a note. She was sorry she’d kept it, but she’d wanted to read it again and again. ‘Hepworth is so right,’ she wrote. I cherish my copy all the more now, like a stone that has been skimmed on the ocean and which, in defiance of time and tide, has at last come skimming back.

Barbara Hepworth was a sculptor, not a writer. Her tools weren’t pen and paper, but chisel and stone. A Pictorial Autobiography is really a scrapbook. There are family photos, school certificates, college diplomas, reproductions of works, gallery pamphlets, press cuttings and assorted archive riflings. We see the infant Barbara in a white smock become Barbar

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign in‘Neither a borrower nor a lender be,’ my grandfather used to say gravely. His caution wasn’t about money. It was about books. Do not lend a book you will want back and do not borrow one you will be sorry to return. Sound advice. Not that I’ve kept to it. Some books I am willing to relinquish. That makes space on my heaving shelves. The loss of others I mourn.

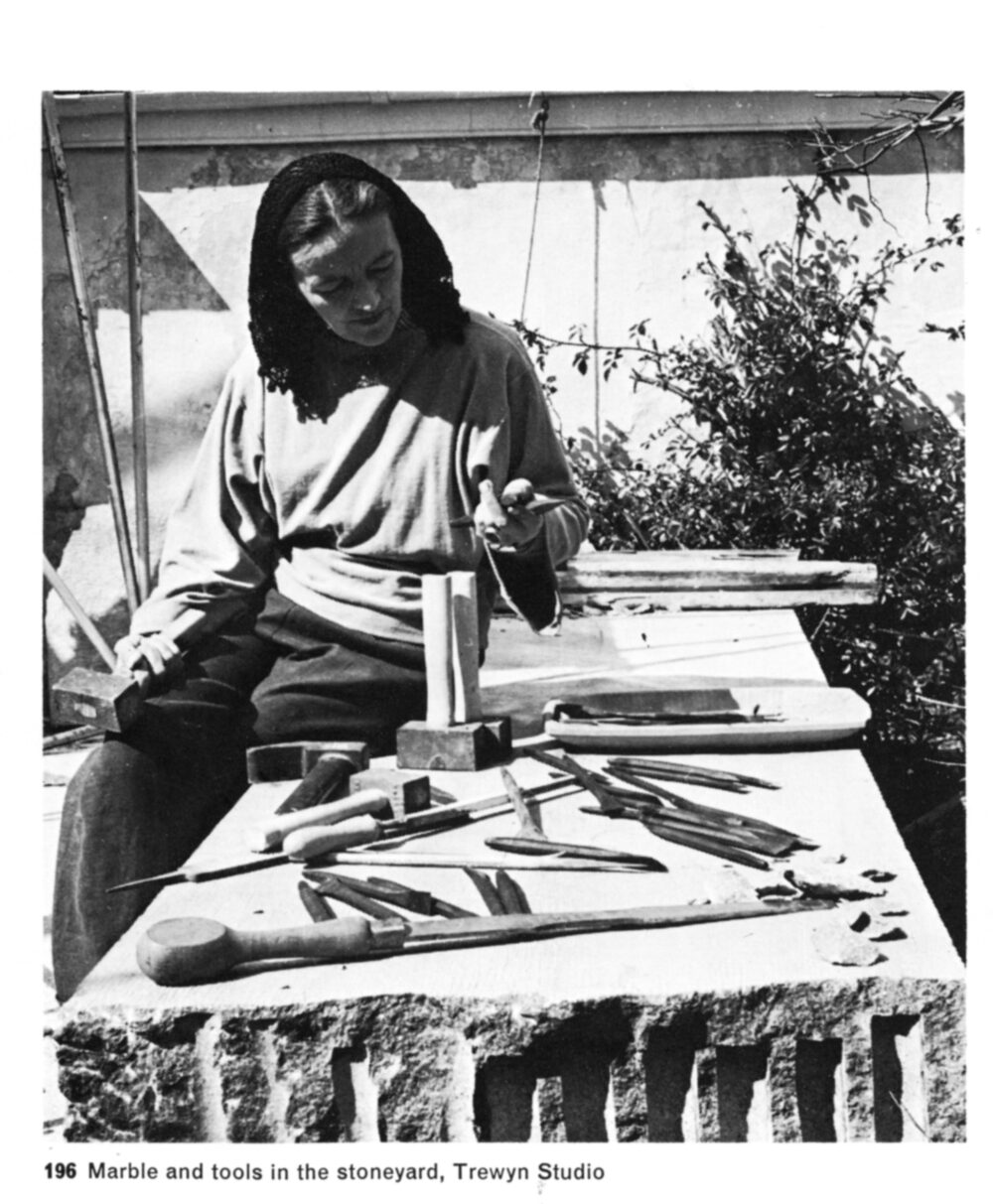

I lent my copy of Barbara Hepworth’s A Pictorial Autobiography to an illustrator friend who, for reasons of distance and diaries, I rarely see. We had been talking about children and creativity and whether one must necessarily restrict the other: the easel, the laptop, the pram in the hall. I said she must read Hepworth and posted her my copy. It arrived. She thanked me. After that: nothing. Nothing for months and months and a year, and for months after that. I nursed a perverse and very British grievance. I couldn’t possibly ask for it back, because that would be rude. Instead, I did the proper and polite thing of raining resentment, curses and hellfire on her head every time my eye caught the gap in the bookcase. As the second anniversary of the lending approached, I shrugged, shuffled the shelf and wrote the book off as a loss. Then, in the way of watched pots never boiling, the book came back with a hand-painted card and a note. She was sorry she’d kept it, but she’d wanted to read it again and again. ‘Hepworth is so right,’ she wrote. I cherish my copy all the more now, like a stone that has been skimmed on the ocean and which, in defiance of time and tide, has at last come skimming back. Barbara Hepworth was a sculptor, not a writer. Her tools weren’t pen and paper, but chisel and stone. A Pictorial Autobiography is really a scrapbook. There are family photos, school certificates, college diplomas, reproductions of works, gallery pamphlets, press cuttings and assorted archive riflings. We see the infant Barbara in a white smock become Barbara the art student in long beads and split sleeves, become Mrs John Skeaping, sculptor wife to a sculptor husband, become Miss Hepworth, the exhibiting artist, become Mrs Ben Nicholson, mother to triplets, and, at the end of her life, Dame Barbara in workman’s overalls and silk headscarf. There are enchanting contrasts: standing stones and wobbling toddlers, the Venice Biennale and bare, knobbly knees on the beach. The book is like one of Hepworth’s stringed sculptures with threads of text tying the photographs together. (A cartoon clipped from a magazine shows Hepworth seated at a sculpture that looks like an old Singer sewing-machine, pulling a needle through the tops and the sides.) She starts with her childhood in the West Riding, driving through and over the hills in her father’s car, seeing for the first time ‘the hollow, the thrust and the contour’ of landscape. We meet her again at Wakefield Girls’ High School with its ‘gorgeous smell’ of paint. ‘My headmistress knew I detested sports and games,’ Hepworth writes. ‘I loved dancing, music, drawing and painting. And wonderfully, when all had departed to the playing fields I found myself miraculously alone with easel, paints and paper in the school.’ We follow her to Leeds School of Art, the Royal College of Art in London, on a scholarship to Rome, Florence and Siena, to Belsize Park, Hampstead, Paris, Provence and to St Ives where her endless hammering draws endless complaints from the neighbours. The book is like her sculpture in another way, too: it is full of holes. Having married John Skeaping in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence on p.13 and given birth to their son Paul on p.17 – ‘this was a wonderfully happy time’ – two lines later she writes: ‘Quite suddenly we were out of orbit. I had an obsession for my work and my child and my home. John wanted to go free, and he bought a horse which used to breathe through my kitchen window!’ And that is that. John is gone. It is the same with her marriage to Ben Nicholson. They meet in 1931, they have the triplets Simon, Rachel and Sarah in 1934, they marry in 1938, there is the war, they move to St Ives, and then, ‘In 1951, after twenty years of family life, everything was to fall apart.’ No more. Visitors to Trewyn Studio, now the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden in St Ives, are almost obliged to take a picture peering through the space in one of Hepworth’s bronzes, as if it were a seaside photo-board with circles cut out for the faces of pirate and mermaid. Readers of Hepworth’s Pictorial Autobiography find themselves peering through holes in the story, discovering voids where there ought to be form. But this is Hepworth’s story and she tells it in her own way. She began by gathering photographs but found they made the book too personal. She asked her son-in-law Alan Bowness, art historian and husband to Sarah, if he would help. It was Bowness who rooted out the reviews, the catalogues, the photographs of casts and plasters, which made the book, first published in 1970, ‘more work than life, which was what she wanted’. Never mind the holes and withholdings. The fascination of the book, what drew me to it when I first leafed through the pages in the gift shop of Tate Britain’s exhibition ‘Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World’, is sharing in what Hepworth does reveal: how to be an artist, a wife, a mother, a grandmother. How to strike a balance between family life and the life of the mind. How to bear it when the scales can’t and won’t be made to balance. She admits that when the one baby she had thought she was carrying turned out to be three (‘Shut up, Ben, this is no time for jokes,’ said their friends when Nicholson rang with the news), she ‘knew fear’ for the first time in her life. How was she to support a family of four children – 5-year-old Paul and three newborns – on her carvings and on Ben’s white reliefs? How would she make time to make anything at all? What was she without her work? Anyone who has ever counted down to a holiday with the thought: ‘Oh, good, now I can really get some painting/writing/thinking done!’ will recognize the rapture with which Hepworth writes of ‘working holidays’. This habit was established by childhood summers at Robin Hood’s Bay. She had a room in the attic and ‘here I laid out my paints and general paraphernalia and crept out at dawn to collect stones, seaweeds and paint, and draw by myself before somebody organized me!’ These working weeks by the sea, she writes,made a firm foundation for my working life – and it formed my ideas that a woman artist is not deprived by cooking and having children, nor by nursing children with measles (even in triplicate) – one is in fact nourished by this rich life, provided one always does some work each day; even a single half hour, so that the images grow in one’s mind. I detest a day of no work, no music, no poetry.It is these words that struck a chord. They were the words I wanted my friend to read. I am 32. Over and over, I have the same debate: books or babies or both? When I first went freelance five years ago, a friend who had had three children in her early twenties said how wonderful it was that I would never need to bother about an au pair or a nanny: ‘You can just bounce the baby on your knee as you write.’ I said yes, so as not to argue, but thought to myself: there speaks a woman who has never tried to write a steady thousand words a day. Another friend, also a mother of three children, aged 6, 4 and 20 months, had different advice. I had said I was in awe of how many new novels she managed to read. There was an hour each weekday when the two older children were at school and the youngest child was having her nap. ‘I decided I could use that time to tidy up,’ she said, amid the chaos of the kitchen, ‘or I could use it to read my book.’ As wife, mother and sculptor, Hepworth got it right and she got it wrong, but she got some work done every day. I have lost count of the number of books and articles I have read telling me to lean in and get on and rise up and be the boss and smash the ceiling and beat the boys. None have stayed with me as Hepworth has, none have done so much to inspire and spur and reassure. ‘Even a single half hour.’ The words are carved on my heart.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 69 © Laura Freeman 2021

About the contributor

Laura Freeman is writing a biography of Jim Ede and the Kettle’s Yard artists, one of whom is Barbara Hepworth.