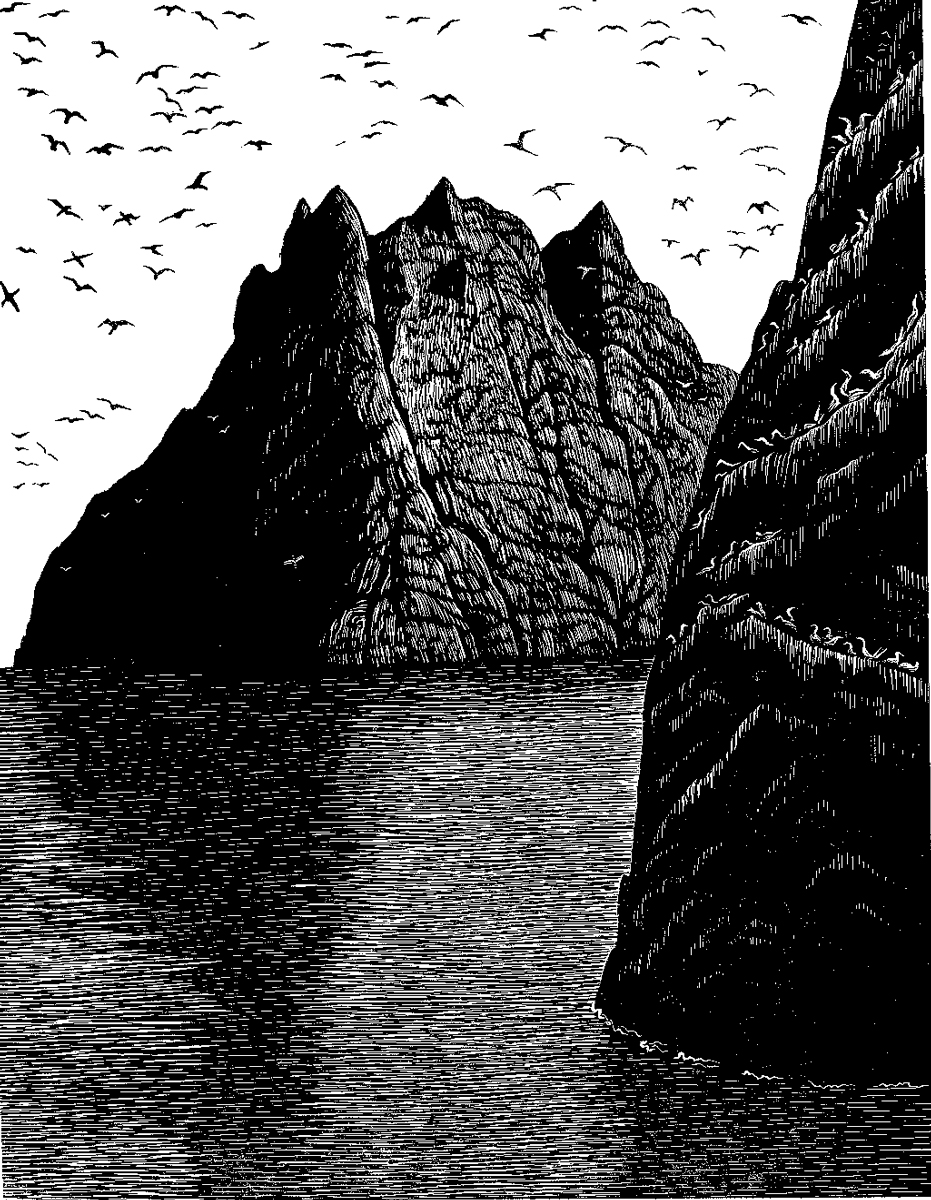

In shelves to the left and right of the fireplace in our dining-room, my husband keeps an extensive collection of books about Scotland. Half a shelf is given over to volumes on St Kilda. If ever I feel the need to escape from Hammersmith to a landscape of vast skies, mountainous waves, sea-spray blowing like white mares’ tails across the rocks, this is where I turn: to the extraordinary archipelago, 110 miles west of the Scottish mainland, whose black cliffs and dizzying stacks, the highest in Britain, unfold in a drumroll of Gaelic names – Mullach Mor, Mullach Bi, Conachair.

Inhabited for over a thousand years, St Kilda wasn’t properly mapped until 1928, and the lives of the islanders, though well documented, seem to push at the boundaries of credibility. Old sepia photographs show short, stocky men in tam-o’-shanters, dirty white woollen jerkins and plaid trousers, out of which stick bare feet with claw-like toes, formed over years of swarming up practically sheer cliffs to catch birds, which they then tucked into their belts. Despite being surrounded by the sea, the St Kildans’ main diet was not fish but fulmar, gannet and puffin.

Swept by salt winds, crops were poor: there were few vegetables, and no fruit. When the first apple was brought to the islands in 1875, it caused consternation. News arrived slowly: the islanders kept praying for the good health of William IV long into the reign of Queen Victoria. If they felt the need to send letters to the mainland, the St Kildans would stuff them into ‘mailboats’ – hollowed- out lumps of wood inscribed PLEASE OPEN– and launch them into the sea like messages in bottles. If they required more urgent attention, they lit bonfires, hoping to catch the attention of crofters 45 miles east on North Uist.

The islanders had looms, cows, sheep, dogs. Some had shoes fashioned from the carcasses of gannets. But perhaps the best way to get a feel for these cragsmen-crofters is to make a list

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIn shelves to the left and right of the fireplace in our dining-room, my husband keeps an extensive collection of books about Scotland. Half a shelf is given over to volumes on St Kilda. If ever I feel the need to escape from Hammersmith to a landscape of vast skies, mountainous waves, sea-spray blowing like white mares’ tails across the rocks, this is where I turn: to the extraordinary archipelago, 110 miles west of the Scottish mainland, whose black cliffs and dizzying stacks, the highest in Britain, unfold in a drumroll of Gaelic names – Mullach Mor, Mullach Bi, Conachair.

Inhabited for over a thousand years, St Kilda wasn’t properly mapped until 1928, and the lives of the islanders, though well documented, seem to push at the boundaries of credibility. Old sepia photographs show short, stocky men in tam-o’-shanters, dirty white woollen jerkins and plaid trousers, out of which stick bare feet with claw-like toes, formed over years of swarming up practically sheer cliffs to catch birds, which they then tucked into their belts. Despite being surrounded by the sea, the St Kildans’ main diet was not fish but fulmar, gannet and puffin. Swept by salt winds, crops were poor: there were few vegetables, and no fruit. When the first apple was brought to the islands in 1875, it caused consternation. News arrived slowly: the islanders kept praying for the good health of William IV long into the reign of Queen Victoria. If they felt the need to send letters to the mainland, the St Kildans would stuff them into ‘mailboats’ – hollowed- out lumps of wood inscribed PLEASE OPEN– and launch them into the sea like messages in bottles. If they required more urgent attention, they lit bonfires, hoping to catch the attention of crofters 45 miles east on North Uist. The islanders had looms, cows, sheep, dogs. Some had shoes fashioned from the carcasses of gannets. But perhaps the best way to get a feel for these cragsmen-crofters is to make a list of what they did not have: horses, ploughs, spades, locks, money, laws, crime. St Kilda is top of the list of places I hope to visit before I die. So imagine my amazement when I discovered that two roads away from us in London lives a woman who has not only been there, but has also written a novel based on Hirta, the main island. An archaeologist by training, Karin Altenberg was fed up with her job when she decided to journey to St Kilda, to blow away the cobwebs and think clearly about her future. She was to have travelled to the islands with a lobster fisherman but – as often happens – the Atlantic surges were too perilous. She caught a lift instead on a yacht. After eight hours’ sailing, the cliffs of St Kilda loomed up ahead – ‘like Mordor’, says Karin’s partner, the poet Robin Robertson. The clouds lifted and the sun came out. The combination of light and mist was, Karin says, ‘otherworldly’. No visitor is allowed to stay on St Kilda, so in the few hours she had there she rushed about taking in everything she could – the ‘clachan’, a huddle of oval dwellings, a bit like puffin burrows, in which the St Kildans lived until the mid-nineteenth century; the stone houses of the ‘new’ village; the plain, austere church built to plans drawn up by the great lighthouse builder Robert Stevenson (grandfather of Robert Louis). As she re-boarded the yacht to sail back to Scotland, an idea began to form in her mind. She would capture St Kilda not by employing her training as an archaeologist and historian, but through fiction. Island of Wings, published in 2011, centres on a real Church of Scotland minister, Neil MacKenzie, who arrived on St Kilda in 1829 with his wife, Lizzie. The novel is, in a sense, a portrait of their marriage. MacKenzie is handsome, courteous, filled with zeal as he plans to convert the islanders from near-savages into upstanding Christians. He is fastidious – newspapers arrive months late on St Kilda, so he makes a point of reading a paper on the same date it was published, but a year on – and, when crossed, he is prone to violent rages. Though he knows he should love his flock, he is revolted by the way they live:The beds are dug out of the thickness of the walls, and the entrance to these grave-like beds is two by three feet. Ashes, dirty water and far worse are spread daily on the earth floor and covered every few days with more ashes. This way, they tell me, the thickness of the floor accumulates over the year so that by springtime, before this human manure is dug out and spread across the fields, the inhabitants have to crawl around their houses on their hands and knees.Lizzie, though she arrived on St Kilda not understanding a word of the islanders’ Gaelic, is less hidebound, more sympathetic: a freer spirit. In one of the most magical passages in the novel, she walks naked into the sea on a warm summer night and is illuminated by phosphorescence. Over time, it is Lizzie, not Neil, who forges friendships. But life on St Kilda, while sometimes enchanting, can be darkly terrifying, even to Lizzie. Her first child, Nathaniel, dies in an agony of cramps and convulsions within a few days of birth. One of the island women, Betty, having lost six infants in the same way, tries – unsuccessfully – to hang herself. Betty and Lizzie draw close. Neil is fired with jealousy. Fact is the enemy of fiction, some novelists believe. But throughout Island of Wings Altenberg remains true to history. Sixty per cent of babies born in St Kilda died of the ‘eight-day sickness’ – possibly as a result of the fulmar oil wiped on the umbilical stump after birth; possibly simply because the knives used to cut the cords were filthy. Yet though her research is impeccable, you never feel the weight of it: she has read deeply, then flown free. And throughout she evokes the islands – sometimes brooding, sometimes beautiful – with a skill that transports you. ‘The archipelago’, she writes, ‘grew out of the low clouds like bad teeth in a weak mouth.’ ‘Somewhere in the west a thin band of light was breaking through the North Atlantic mist, dyeing it the colour of old sheets.’ Gannets appear ‘whitewashed and graceful with heads that looked as if they had been dipped in custard’. The sea mist rolls in over the island ‘like the smoke of a spent battle’. In early spring, when the islanders are close to starvation, waiting for the birds to return from the west, they are pelted with hail ‘as big as fulmar eggs’, while sheep blow off the cliffs ‘like drifting snow’. This spellbinding imagery is all the more remarkable when you know that English is not Karin Altenberg’s first language. Brought up in Sweden, where she taught herself a bit of English by reading The Golden Treasury and singing along to pop music, she only arrived in the UK, to take up an Erasmus scholarship, when she was 22. Perhaps it’s because she has to think hard about words that she writes with such beautiful precision. Neil MacKenzie was greatly admired by his Church of Scotland brethren on the mainland – and rightly so. Under his supervision, the St Kildans left their fetid burrows and built themselves stone crofts, with drains. In Island of Wings, he strips down to his shirtsleeves to join in the heavy work alongside the men. He persuaded benefactors in Scotland to donate beds, crockery, chamber pots. But this ‘improvement’ was double-edged. ‘Faced with the prejudices of the outside world,’ Altenberg writes, ‘the islanders understood they were lacking in something important, something that would make them human in the eyes of the world.’ Equality and co-operation, for which the St Kildans had been famed, gave way to mistrust and jealousy. Spiritually, meanwhile, they resisted MacKenzie’s teaching. ‘They can repeat the catechism like a child repeats a nursery rhyme,’ MacKenzie writes. ‘But they do not seem to feel the weight of its truth on their souls.’ Why believe in the Gospel miracles when their own pagan superstitions were so enchanting? Pluck a live puffin, the St Kildans believed, and its feathers would grow back as white as snow. His equilibrium upset by the islanders’ resistance to instruction, MacKenzie suffers a mental collapse. Island of Wings closes in May 1843, with the departure of the MacKenzies after fourteen years on St Kilda. But I can’t resist fast-forwarding from this point to 29 August 1930 when, after two impossibly harsh winters, the 36 men and women still living on St Kilda were evacuated to Scotland. Many were provided with jobs working for the Forestry Commission – ironic, since they had never seen trees. They were desperately homesick, and most died before the outbreak of the Second World War, some of the common cold, which they had never before encountered. As they had prepared to depart from St Kilda, they had lit fires in their hearths, and left their bibles open at the Book of Exodus.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 73 © Maggie Fergusson 2022

About the contributor

Maggie Fergusson is the author of George Mackay Brown: The Life, and Literary Editor of The Tablet. London-bound, she yearns to be in St Kilda. You can also hear her discussing the life and work of George Mackay Brown on our podcast, Episode 11, ‘Orkney’s Prospero’.