Every Friday afternoon I go to work in our local Amnesty secondhand bookshop, and each week I notice a shabby cover of a book entitled If Jesus Came to My House stuck on one of the walls. Few people see this unusual decoration as it is over the back stairs, with an admonitory notice next to it which reads, ‘This slim tatty little volume sold for £30.’ The book in question was sold by the shop’s Internet team, and serves to remind the staff that they may not know what a book is worth until they start selling it to someone else.

With new and second-hand bookshops closing all over the country, how does our bookshop survive, flourish and send thousands of pounds to Amnesty International every year? Naturally it helps that all the books are donated and the shop is run by twenty-six volunteers. The Volunteer Co-ordinator told me during my induction that ‘we have an entirely flat management structure. No one is more important than anyone else.’ Anyone who has worked in an organization of more than two people knows that this has always been a Utopian dream, but it is still an admirable principle. It may also be necessary in this context as charity-shop work tends to attract retired people who can experience sudden health problems. ‘We have three heart conditions here,’ said the Co-ordinator imperturbably.

What is required of the voluntary staff? They clearly need to be literate and numerate and to have patience with the moodiness of the ancient till, but much of the success of the shop depends on those who have developed an appreciation of the monetary value of books which only comes with experience. A new volunteer with a working knowledge of Shakespeare, English poetry, nineteenth-century fiction and Booker prize winners will not know how to price a book called A Dictionary of Poultry. Or again, a title like Medieval Church Screens of the Southern Marches may not be universally appealing, but a check on the I

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inEvery Friday afternoon I go to work in our local Amnesty secondhand bookshop, and each week I notice a shabby cover of a book entitled If Jesus Came to My House stuck on one of the walls. Few people see this unusual decoration as it is over the back stairs, with an admonitory notice next to it which reads, ‘This slim tatty little volume sold for £30.’ The book in question was sold by the shop’s Internet team, and serves to remind the staff that they may not know what a book is worth until they start selling it to someone else.

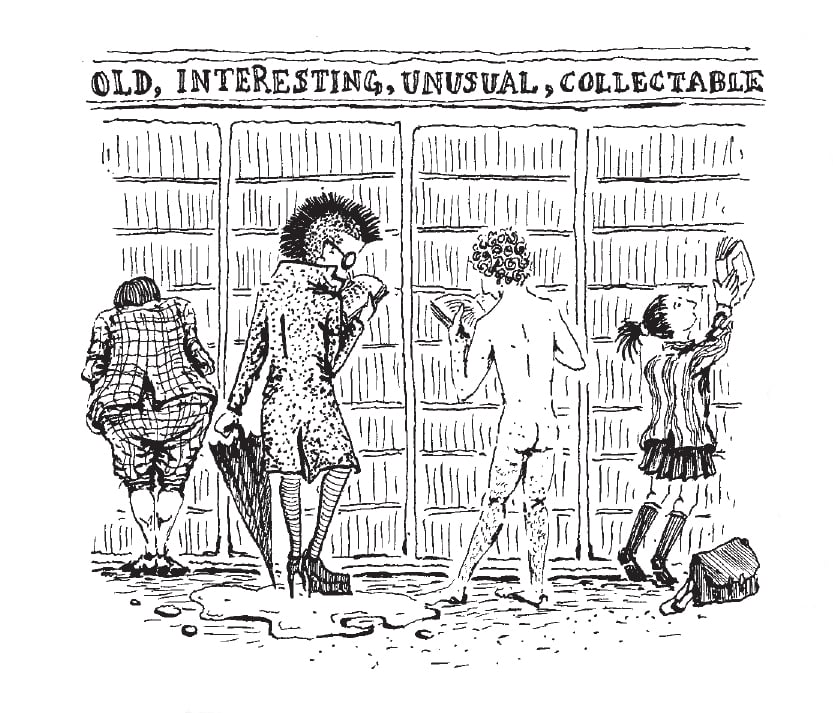

With new and second-hand bookshops closing all over the country, how does our bookshop survive, flourish and send thousands of pounds to Amnesty International every year? Naturally it helps that all the books are donated and the shop is run by twenty-six volunteers. The Volunteer Co-ordinator told me during my induction that ‘we have an entirely flat management structure. No one is more important than anyone else.’ Anyone who has worked in an organization of more than two people knows that this has always been a Utopian dream, but it is still an admirable principle. It may also be necessary in this context as charity-shop work tends to attract retired people who can experience sudden health problems. ‘We have three heart conditions here,’ said the Co-ordinator imperturbably. What is required of the voluntary staff? They clearly need to be literate and numerate and to have patience with the moodiness of the ancient till, but much of the success of the shop depends on those who have developed an appreciation of the monetary value of books which only comes with experience. A new volunteer with a working knowledge of Shakespeare, English poetry, nineteenth-century fiction and Booker prize winners will not know how to price a book called A Dictionary of Poultry. Or again, a title like Medieval Church Screens of the Southern Marches may not be universally appealing, but a check on the Internet shows that some people are currently prepared to pay £20 or more for it. Popularity has nothing to do with value, and the most prized books are often on rarefied subjects. Not all donations are valuable but all are accepted. This does not mean that they will all be priced and shelved, but even the redundant encyclopaedias and out-of-date hotel guides are not wasted. The grimy and shabby, or those that have sat on the shelves too long, are parcelled up and collected by a recycling firm which pays a modest amount to take them away and turn them into fabric. Donors are encouraged to bring books to the shop in bags or boxes, but passersby sometimes slip a couple of books round the door, announcing cheerfully, ‘Got some more books for you!’ Heavy loads may have to be collected by car. This encourages donations and is well worth doing, because the most interesting and valuable books are often found in personal libraries during house clearances. In the world of second-hand books the old and dusty are treasured not despised. Our shop is small and space is at a premium. What kinds of books can profitably be sold? Serious book-lovers tend to look first at the section labelled ‘Old, Interesting, Unusual, Collectable’, a category which contains an eclectic mix of books, often with some rarity value. A large area is devoted to contemporary and popular fiction, where the paperbacks sell for twice the price of the hardbacks, because the hardbacks are twice as hard to sell. All items are priced at 50p in the children’s section to encourage the young to read and grandparents to buy. The 3-year-olds choose Peppa Pig and their grandmothers buy Black Beauty. There are currently large sections devoted to biography, history, travel and health, and small sections to philosophy, humour and management studies. Local history books have no permanent section because they are always in demand. Copies of books already in stock may be allocated to the nearest hospice, while boxes of educational books find their way to a schools project in Sierra Leone. Less desirable books end up on the Bargain shelves at 50p. The main emphasis is on a swift throughput in all sections so there is always fresh interest for customers. Occasionally I am tempted to think that the customers resemble the books, especially those that are well-worn, unfashionable and unexpectedly interesting. I once told an old man asking for Hungarian books that there was not much demand for them and that Magyar was a very difficult language. ‘I know,’ he said. ‘It was my first language and I’ve forgotten it.’ Some customers like to tell you who the book is for or why it’s been chosen – a book about vinegar ‘for my sister, because they say cider vinegar is good for arthritis’. Other customers have more romantic preoccupations. One starry-eyed girl asked if the shop stocked the white hardcover Nelson edition of Pride and Prejudice because she wanted her wedding ring to be placed on it during her marriage ceremony. Not everyone is charming or amusing. Long-time volunteers tell stories of past customers with ‘anger management issues’, or of the exhibitionist who dived into the sacks of unwanted books and then started to strip off to his underwear. The team launched an on-line shop in 2005 and now sells books all over the world, making a substantial contribution to the profits. Courtesy and speedy delivery are appreciated. One lady not only sent her thanks but also said what a pleasure it was that the parcel was ‘addressed in educated handwriting’. Over 2,000 books are now kept in stock, perched perilously on the upper floors, and occasionally a human chain has to be organized to shift the books from one area to another. Each Internet book description says that all profits go to Amnesty International and many customers say how pleased they are to support the charity. The shop supports Amnesty financially without being part of its organization, but generous buyers may say ‘keep the change’ or make a small donation. The bookshop is situated on a steep hill and parking outside is usually impossible. What persuades people to make the physical effort required to reach us? We see regular customers who are clearly addicted to books and buy by the bagful, and serious book buyers who are looking for bargains. We try to help those who have a definite quest and it is mutually satisfying when we find what they want. We recognize that some people just come in from the cold to browse and ruminate at leisure and that those who look a little lonely may need books as friends. Old books generate a special atmosphere which is both mentally stimulating and physically comforting: I can confidently say that none of us would get half as much pleasure and satisfaction from a room full of Kindles.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 37 © Marie Forsyth 2013

About the contributor

Marie Forsyth is surrounded by books at home and at work. Occasionally she feels the need to go into competition and write herself. She writes very slowly in French to friends in France and very quickly in English to everyone else.