The words on Alan Ross’s gravestone could hardly be simpler: ‘Writer, poet and editor’. They could scarcely be more accurate either, although one wonders whether their subject might have given his commitment to poetry pride of place. Alan is buried in the churchyard in Clayton, the Sussex village where he lived for twenty-five years and where he knew great happiness. That happiness was particularly precious to a man who also experienced the fathomless miseries of depression. In Coastwise Lights (1988), his second volume of autobiography, Alan writes,

Our house, which in its day had been successively Roman villa, farm and, more recently, rectory, looked westwards through an orchard, past Clayton church and farm, towards the great hump of Wolstonebury, whose slopes were rusted with beech woods. Sheer to the south the sky was bisected by the line of the Downs, crowding in and falling away as far as the eye could see.

Chelsea was another of Alan’s haunts and his life in literary London also features prominently in the book; he lived in an Elm Park Gardens flat immediately after the war and died in a cottage in Elm Park Lane in 2001. This metropolitan base was essential for work: Alan was the editor of London Magazine for forty years, during which time he offered encouragement and hope to very many aspiring writers who wondered doubtfully whether a literary life was for them. Such blessings are still available to those who read his four volumes of autobiography or his other prose about travel, cricket and India. Poetry, though, lies at the heart of all his work.

Coastwise Lights begins roughly where Blindfold Games, Alan’s first volume of autobiography, ends. Having recently left the navy, we find him in the post-war world attempting to make a living by writing. Yet even more than its predecessor, the second book tries to marry a broad linear narrative with a detailed account of episodes

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe words on Alan Ross’s gravestone could hardly be simpler: ‘Writer, poet and editor’. They could scarcely be more accurate either, although one wonders whether their subject might have given his commitment to poetry pride of place. Alan is buried in the churchyard in Clayton, the Sussex village where he lived for twenty-five years and where he knew great happiness. That happiness was particularly precious to a man who also experienced the fathomless miseries of depression. In Coastwise Lights (1988), his second volume of autobiography, Alan writes,

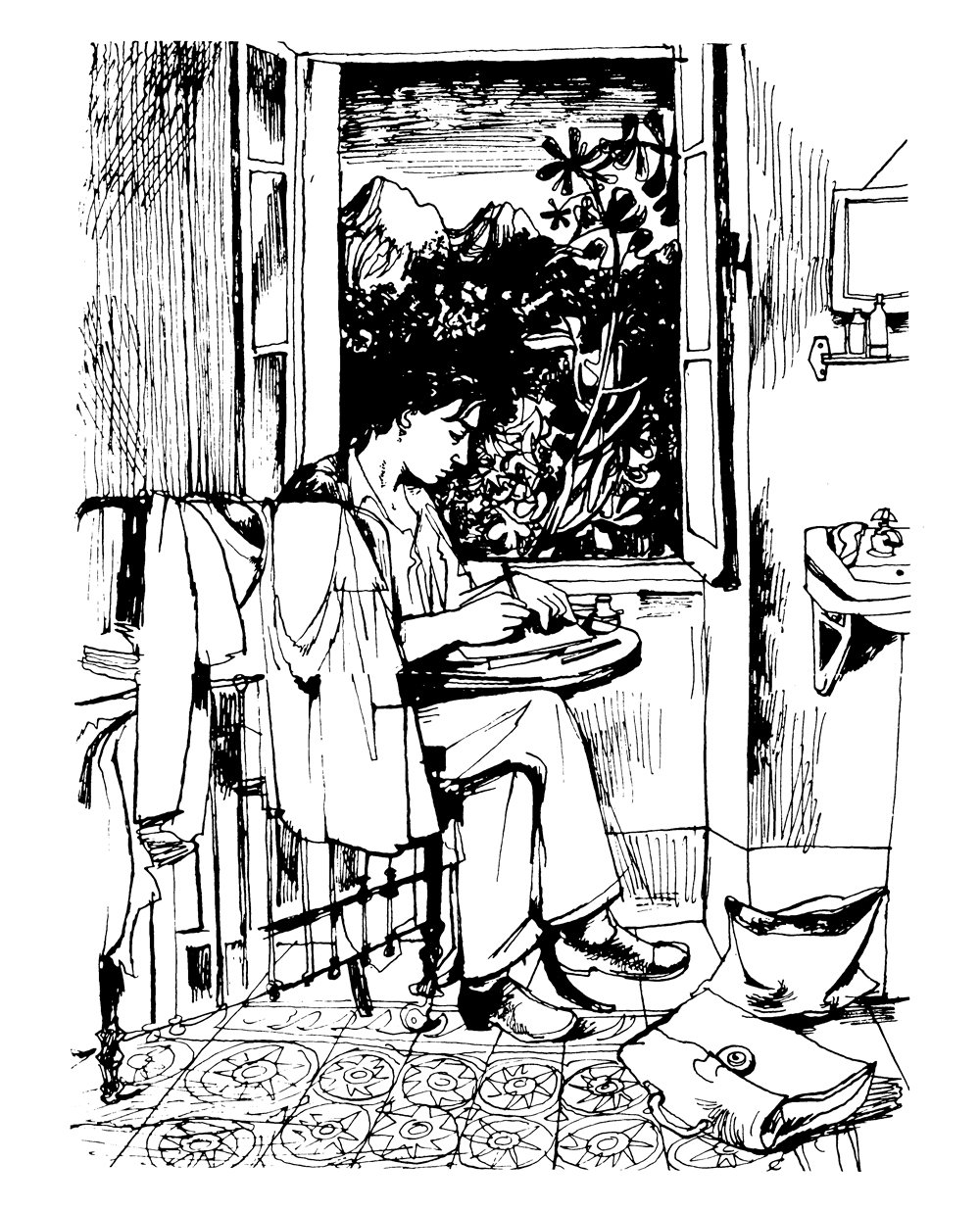

Our house, which in its day had been successively Roman villa, farm and, more recently, rectory, looked westwards through an orchard, past Clayton church and farm, towards the great hump of Wolstonebury, whose slopes were rusted with beech woods. Sheer to the south the sky was bisected by the line of the Downs, crowding in and falling away as far as the eye could see.Chelsea was another of Alan’s haunts and his life in literary London also features prominently in the book; he lived in an Elm Park Gardens flat immediately after the war and died in a cottage in Elm Park Lane in 2001. This metropolitan base was essential for work: Alan was the editor of London Magazine for forty years, during which time he offered encouragement and hope to very many aspiring writers who wondered doubtfully whether a literary life was for them. Such blessings are still available to those who read his four volumes of autobiography or his other prose about travel, cricket and India. Poetry, though, lies at the heart of all his work. Coastwise Lights begins roughly where Blindfold Games, Alan’s first volume of autobiography, ends. Having recently left the navy, we find him in the post-war world attempting to make a living by writing. Yet even more than its predecessor, the second book tries to marry a broad linear narrative with a detailed account of episodes which encapsulated Alan’s passions and style of life. This impressionism is even more pronounced in his next two volumes of autobiography, After Pusan and Winter Sea. The first begins with a thirty page memoir of Alan’s visit to the South Korean coastal city along with a consideration of the late nineteenth-century explorer Isabella Bird; it ends with eighty pages of poetry, the first Alan had written following prolonged depression. Winter Sea is subtitled ‘War, Journeys, Writers’ and is dominated by Alan’s return to the Baltic, a sea in which he had nearly died fifty years previously. As always, there is poetry; as always, there is an insightful reading of somewhat neglected literary figures: the Norwegian writer Nordahl Grieg and the Estonian poet Jaan Kaplinski. These last two books are also briefer than either Blindfold Games or Coastwise Lights; perhaps they should properly be categorized as memoirs. But one is never surprised to find Alan stretching a genre, the better to reflect his experience, the better to accommodate the subtle rhythms of his prose. These characteristics are abundantly displayed in the opening section of Coastwise Lights. We find Alan and the painter John Minton in Montparnasse, where they are staying in a cheap hotel en route to Corsica, the subject of their travel book Time Was Away. Already two of the autobiography’s themes, travel and art, have been introduced. The title of the Corsican book is taken from Louis MacNeice’s famous poem but Coastwise Lights is also interspersed with groups of poems used, as Alan writes in the preface, ‘as illustrations and to fill in a few gaps’. Readers expecting to learn much about Alan’s adult family life might be disappointed by all four volumes of his autobiography. They will be told relatively little about girlfriends, wives, children. Family members are glimpsed in passing before their presence is quickly woven into broader developments. This is not to say that personal relationships are omitted from Coastwise Lights. On the contrary, the book’s richest theme is that of friendships, whether formed with painters like Keith Vaughan or authors such as Henry Green or William Plomer. Often one is sent back to writers one has heard of but does not really know. Like so many of Alan’s books, Coastwise Lights can be an expensive purchase, not because it costs very much but because it leads one to curiously neglected authors from the second half of the last century. For if a critic as tough and sensitive as Alan liked a writer, they must have something. Alan’s appreciation of writers like William Sansom or Bernard Gutteridge is warm but his assessment is unsweetened by fondness. Take, for example, this on Sansom:

On his bad days he could be taken for a bookmaker drowning his sorrows. There was an Edwardian courtliness to Bill’s sober manner – and he was usually sober three weeks out of four – a bowing to ladies and a kissing of hands. He took to wearing a musky, extremely pervasive scent, which gave him a sweet, bear-like aroma. He tended to brush his rather fine hair straight back, not quite en brosse, but in the manner of an Italian tenor like Tino Rossi. I never saw it remotely ruffled, not even when he had fallen over.Much of Coastwise Lights is devoted to descriptions of foreign travel. Alan was born in Calcutta, and his love of Sussex, where he was sent to school, was fostered partly by his need for an English Heimat and partly by his lifelong love of cricket. Yet he lost neither the urge to wander nor the desire to return to the South Downs. Kipling’s lines, ‘Swift shuttles of an Empire’s loom that weave us main to main / The Coastwise Lights of England give you welcome back again’ supply much more than a title for the book. They capture one of its essences. Thus we begin with Alan in Montparnasse, looking out through the ventilation panel in the toilette of his cheap room and watching a domestic drama taking place in the apartment a few feet away. It is the sweltering summer of 1947 and all three participants he observes are naked. What Ross finds intriguing is the incongruity of the trio’s behaviour; what the reader notices is the acuity of observation, the curiosity of the born writer. Other foreign trips are slightly more conventional but no less sharply realized. For four years Ross works for the British Council and accompanies its Controller of Education on a trip to Baghdad. On the flight from Rome to the Middle East he sits next to Agatha Christie. Eventually it is arranged that he will go on a shooting trip to the marsh country near Basra where he will enjoy the hospitality of the local sheikhs in their mudhifs on the banks of lagoons. He visits a now vanished world made famous by Wilfred Thesiger and Gavin Maxwell. ‘The few days I spent in the marshes were a kind of dream, coloured the green of reeds, the blondness of corn, the gunmetal shimmer of water, the pale bronze of sky.’ There are echoes of Edward Thomas here. The prose, as Ross recognizes, is often raw material for poems which are, to a degree, a different distillation of experience. The trip to Iraq was Ross’s first and last foreign adventure with the Council. Three years later he obeyed his obvious vocation and became a part-time freelance journalist. He had already published poetry, made translations and written essays on American authors, but the writing life was now the whole commitment and it remains a dominant theme of Coastwise Lights. While becoming well connected in the literary world – Harold Nicolson and Cyril Connolly were friends – he also expressed a then unconventional desire to write about sport. Before long he was filing football reports for the Observer and in 1953 he became the paper’s cricket correspondent, a post he occupied for eighteen years. Cricket writing, as some of those involved in it rarely recognize, is a niche activity. For every book which transcends the genre there are ten which remain clotted by statistics and routine match reports. What Alan succeeds in doing is taking moments on the cricket field and suggesting their relationship to other arts and different skills. One of his aims, as he wrote elsewhere, was to ‘preserve a style, restore an action, rehearse an elegance’. The result is some of the finest cricket books we have and a body of other work in which style is bound to content. Cricket may sometimes seem a little distant but poetry is never far away. I am sure Alan would be happy with this. Blindfold Games is, he writes, ‘an attempt to reconcile differing definitions of style and to trace the manner in which a single-minded devotion to sport developed into a passion for poetry’. Coastwise Lights continues that journey as the writer grows more confident in his gifts. In 1961 Alan took over The London Magazine and changed more or less everything about it. The definite article was ditched, as was the dull cover. Under Alan’s editorship coverage was extended to art, cinema, architecture and music. The magazine’s archive, which is housed in the University of Leeds’s Brotherton Library, contains hundreds of letters in which young writers ask Alan to consider their poems or short stories. The swiftness of the response was legendary and further correspondence is often filled with grateful appreciation of Alan’s encouragement or acceptance. The same library also contains the manuscripts of Blindfold Games and Coastwise Lights, many of the chapters written in the author’s graceful hand on stationery liberated from distant hotels. One section of Coastwise Lights concerns Alan’s involvement with London Magazine from the editor’s perspective and chronicles the wideranging expansion into publishing which brought the work of Barbara Skelton, Julian Maclaren-Ross and Tony Harrison to a wider audience. ‘Publishing has always been for me an amateur activity in the strictest sense of the word,’ he writes; ‘it was never my livelihood, nor have I ever earned a penny out of it. But, since it was a labour of love, there was all the more reason for it to be done to the highest professional standards.’ Coastwise Lights concludes with a section about horse-racing, another of Alan’s passions and one facilitated in Clayton by the proximity of the small courses he loved. And so this book ends in Sussex with a description of village life and one of the finest final paragraphs in English prose. When serving on the deadly Baltic convoys in the Second World War, Alan had been sustained by the possibility of somehow returning to the county in which he eventually lived. The more remote that possibility seemed, the more vital it became to hold on to it. Earlier in Coastwise Lights Alan describes his move to Clayton:

During my sea-time I used to dream of Sussex; not so much a specific Sussex as a generalized romantic image conjured out of memory and hope. Sussex cricket played a large part in it, to the extent that I had only to see the word Sussex written down, in whatever context, for a shiver to run down my spine. Such an association might properly belong to adolescence, but it has survived. Now the dream was reality and for the next twentyfive years Sussex was my home, London a mere work-place.Unlike the writers whose work he published, Alan is not in want of champions. For some cricket writers he is an example to which they might, on their best days, aspire. For writers of any sort, he manages, albeit after death, to offer something of the same encouragement he did when he ran London Magazine. Very recently, Gideon Haigh wrote this about Alan’s cricket writing: ‘His work stands the test, I think, precisely because of the delight Ross took in his task, of crafting prose up to the standards of the players he was watching – a writer’s writer, but of his subjects like an alert and observant partner.’ And then there is another writer. He has spent days in the Brotherton Library; he has wandered around Chelsea on murky autumnal evenings; and he has tramped the Downs around Clayton on summer afternoons when ‘the landscape flows and brakes, chalkslashed, tree-shadowed, its lanes dusty, partings in squares of corn’. He has done these things neither because Alan needs a biographer nor because he is, at least in part, a cricket writer. He has done them because he is fascinated with the mysterious process whereby one of his closest relationships has been formed with someone he never met; and because it is almost always Alan and hardly ever Ross.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 66 © Paul Edwards 2020

About the contributor

Paul Edwards is a former teacher who now spends much of each summer watching cricket and writing about it for The Times, Cricinfo, The Cricketer and other publications.