Fifteen years ago I set out to invent a fictional detective to lead a series that I hoped would stretch to half a dozen novels. The great imperative was to come up with a character I could live with, a sort of notional flatmate whose habits, tics and jokes I would still be able to tolerate over a span of five or six years. To date Titus Cragg and I have cohabitated more than twice as long, and I still have no inclination to ask for his keys and show him the door.

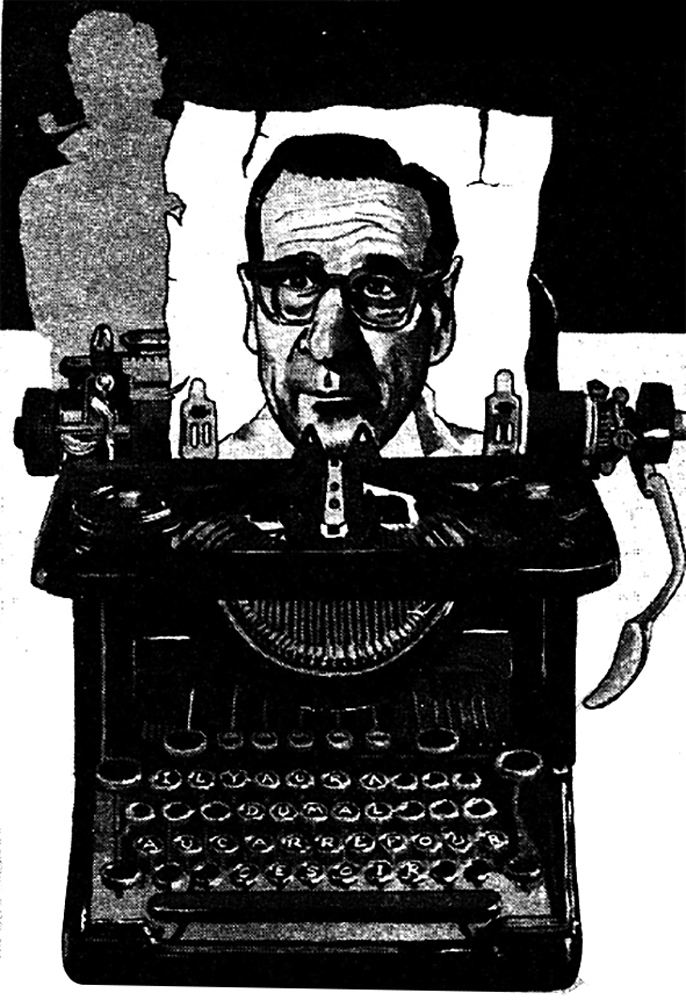

In or around 1930 the 27-year-old Belgian-born writer Georges Simenon faced a similar problem. Under various pseudonyms he had been vastly productive of pulp fiction, a typewriting Stakhanov of the roman à sensation, but his driving ambition was to establish his name in literary fiction. As a first step he chose the genre of the policier and, for a lead character (or imaginary friend), came up with Paris commissaire Jules Maigret. The pair were compatible from the start and over forty years the commissaire featured in seventy-five novels from Pietr the Latvian (1931) to Maigret and Monsieur Charles (1972), as well as thirty or forty short stories.

Appearing in English translation at an early stage, Maigret found himself up against the great detectives of the Golden Age. These characters – Poirot, Wimsey, Campion and Grant et al. – were less like real people than super-heroes with brilliant, even unearthly skills disguised under an absurd, or maybe just an ordinary front. Maigret, while he appeared deeply ordinary, was emphatically not a super- hero underneath.

Maigret was tall and wide, particularly broad-shouldered, solidly built, and his run-of-the- mill clothes emphasized his personal stockiness. His features were coarse and his eyes could seem as still and dull as a cow’s. In this he resembled certain figures out of children’s nightmares, those monstrously big, blank-faced creatures that bear down upon sleepers as if to crush them.

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inFifteen years ago I set out to invent a fictional detective to lead a series that I hoped would stretch to half a dozen novels. The great imperative was to come up with a character I could live with, a sort of notional flatmate whose habits, tics and jokes I would still be able to tolerate over a span of five or six years. To date Titus Cragg and I have cohabitated more than twice as long, and I still have no inclination to ask for his keys and show him the door.

In or around 1930 the 27-year-old Belgian-born writer Georges Simenon faced a similar problem. Under various pseudonyms he had been vastly productive of pulp fiction, a typewriting Stakhanov of the roman à sensation, but his driving ambition was to establish his name in literary fiction. As a first step he chose the genre of the policier and, for a lead character (or imaginary friend), came up with Paris commissaire Jules Maigret. The pair were compatible from the start and over forty years the commissaire featured in seventy-five novels from Pietr the Latvian (1931) to Maigret and Monsieur Charles (1972), as well as thirty or forty short stories. Appearing in English translation at an early stage, Maigret found himself up against the great detectives of the Golden Age. These characters – Poirot, Wimsey, Campion and Grant et al. – were less like real people than super-heroes with brilliant, even unearthly skills disguised under an absurd, or maybe just an ordinary front. Maigret, while he appeared deeply ordinary, was emphatically not a super- hero underneath.Maigret was tall and wide, particularly broad-shouldered, solidly built, and his run-of-the- mill clothes emphasized his personal stockiness. His features were coarse and his eyes could seem as still and dull as a cow’s. In this he resembled certain figures out of children’s nightmares, those monstrously big, blank-faced creatures that bear down upon sleepers as if to crush them. There was something implacable and inhuman about him that suggested a pachyderm plodding inexorably towards its goal.Compare this with photographs of the author and you see that physically Maigret was not modelled on Simenon. Nor are they alike in other ways. While Simenon thought of himself as being an artist among other artists (which he defined as ‘a sick person, in any case an unstable one’), Maigret couldn’t care less about creativity or the arts and is in any case a model of health and stability. Simenon as a person was hungry for fame, free-spending, restlessly married, sex- addicted, mother-fixated and a disappointed father. His creation (incessant pipe-smoking apart) is nothing like this. Jules Maigret was an alter ego in the literal sense: the flipside of the Simenon coin. Referring to Balzac, but equally to himself, Simenon described a novelist as being one who ‘does not like his mother, or who never received mother love’. He franked this opinion at the age of 70 when, on learning of his mother’s death, he abruptly stopped writing fiction, because now ‘I have nothing to say.’ By contrast, as revealed in the novel Maigret’s Memoirs, Maigret mère plays no part in her son’s life, having died in childbirth when he was 8 with, it seems, no lasting Freudian ill-effects. Then again, while his creator had troubled relationships with his own children, the Maigrets’ marriage in their modest flat on Boulevard Richard-Lenoir is serenely childless. Simenon’s home life included a ménage à trois, and for a time à quatre, but Maigret is never unfaithful to Madame Maigret and she, ever cheerful, is quite incapable of being angry with her husband, despite his long hours at his office on the Quai des Orfèvres and his chronic inability to be back in time for her beautifully cooked dinner. Even Simenon’s famed ability to focus on work (he would finish a novel in less than ten days of ferocious concentration) is not shared by Maigret. This as it happens is crucial to the flavour and structure of the stories, which remain remarkably consistent across the seventy- five titles. At around 30,000 words each, they are novellas rather than novels, but they tell of lurid, bloody and tragic crimes, motivated by failed relationships and hidden secrets. Maigret approaches these in a relaxed, almost lazy way. He likes to play the flâneur, leaving the heavy lifting to his team while he is ‘snooping about’, standing idly at windows or in doorways, or mooching into a local bar where he can eavesdrop on the conversation while downing one glass after another of beer or Calvados. The mundanity of Maigret’s behaviour is the nearest thing he has to a method.(The Hanged Man of Saint-Pholien)

It was Maigret’s way . . . to soak everything up like a sponge, absorbing into himself people and things, even of the most trivial sort, as well as impressions of which he was perhaps barely conscious.In accounting for the enormous commercial success of these books (at their peak there were sales of 3 million a year) Maigret’s personality can hardly be the largest factor. He is a well-balanced individual without hang-ups, and altogether without side. Where, as Philip Marlowe or Sam Spade might put it, is the chin-music in that? One answer lies outside Maigret, in the world he inhabits.(Maigret’s Boyhood Friend)

The wharf was left empty and stagnant, like a drowned landscape. To the right barges rocked on the canal under the moon. A trickle of water escaped through a badly closed sluice. It was the only sound under a sky which was more tranquil and deeper than a lake.

(Lock No. 1)

The detail in Simenon’s wonderful scene-setting is an important component of the narrative tension. Here is Maigret ascending the stairs towards a fourth-floor apartment, where a woman is about to be found murdered.The concierge wasn’t in her lodge. The stairwell had faux marbled walls and a thick red carpet on the stairs, held in place by brass rods. The building smelled musty, as if it was inhabited by old people who never opened their windows, and it was strangely silent, no hint of rustling doors as Maigret and Janvier passed. Only on the fourth floor did they hear any noise, and a door opened.For Anglophone readers with Francophile tendencies, much of Maigret’s appeal lies in Simenon’s evocation of the streets and boulevards of Paris at night, of the evening walk on a maritime esplanade, the first cognac of the day in a provincial zinc bar, the mist over the waters of the Marne or the Meuse. Readers of the Maigret books get well acquainted with French weather: le mistral in the south, la brume in the west, the glaring sun in the perfect blue skies of Provence, the glistening rain on the pavé under yellow urban streetlights. Particular Gallic milieux from the mid-twentieth century reappear again and again in the Maigret books: Belgium with echoes of the author’s childhood world, market towns in la France profonde, coastal Normandy redolent of salty air and crated mackerel, the great network of inland waterways threading through the north-east (as a young man Simenon travelled around on his own barge), the light railways with rubber wheels known as michelines, the rattling urban trams, the hotels de la poste and the seedy city rooming houses. Not the least prominent are the smells of France – pastis, coffee, black tobacco, charcuterie, expensive perfume, garlic, the smell of a market, a seaport, a cheap hotel. Almost all writers on Simenon have stressed the mastery of atmosphere, but this alone was unlikely to make him a multi-million seller. What of the stories he tells? I have seen it argued that he lacked the moral heft of a great storyteller but, in my reading, Maigret always assesses suspects and witnesses by focusing on their moral responsibility. It is not the who, or the where, or the how of a crime, but the why that matters. The characters are never just wooden pieces on an investigative chessboard. Simenon has also been charged with having no feel for tragedy, even though he himself said he wanted to write like the Greek dramatists (and as a writer in French he might have added Racine), keeping his novels short to make them readable in a single sitting, like a classical play. For me the plots are interesting just because of their tragic flavour, concerning as they do the intolerable strokes of misfortune men and women suffer, and the clumsy and incompetent ways in which they deal with them. When Simenon’s son told an interviewer that his father did not believe in evil, I think he meant Simenon had a more dangerous threat in view: destiny. Like a real classical tragedian he regarded destiny as the greatest force pressing down on humanity. At one point in Maigret’s First Case the young policeman fantasizes that his vocation will be that of ‘a mender of destinies’. This is not destiny in the sense of a divine decree. Paul Theroux once called Simenon ‘a hack with an existential streak’. Even if we allow the word ‘hack’, this would have to be the other way around. If Simenon is a moralist, he is an existential kind of moralist and, if he believes in destiny, it is the kind of destiny one creates for oneself. Maigret sees it as his job to unravel tangled patterns of human behaviour that happen to have become criminal. Serial killers, political murders and contract assassins don’t interest him because they lack the muddle of ordinary human motivation. ‘We’re all hopeless prisoners of what we choose to believe,’ Simenon said in an interview. There in the verb ‘choose’ is the note of existential destiny. As in Racinian tragedy, many of the most dramatic moments in Maigret’s stories occur off stage. Maigret himself is not present, so that he (and the reader) gets to know of them through reported speech, either from a subordinate such as Lucas or Janvier, or a witness. Dwelling on these reports, a sudden insight comes to him about a character or a circumstance, a particular action or an apparent coincidence. Casting aside his torpor, he then seizes the case with dogged grip until the truth is shaken out and the characters’ fates are fixed. Maigret often takes a hand in the final outcome, allowing culprits a non-judicial punishment – possibly only to live with what they’ve done – as often as he sends them to gaol or the guillotine. In the highly unlikely event that he reads philosophy Maigret would agree with his near contemporary, the French philosopher Simone Weil, that ‘there is only one thing in modern society more hideous than crime – namely, repressive justice’. It is all told in Simenon’s famous plain style: a vocabulary of around two thousand words, a disdain for adverbs, imagery and writerly effects, and a lot of quick-fire dialogue. The American crime writer Elmore Leonard, also an exponent of raw, pages-long conversations, said that ‘if it sounds like writing I rewrite’. Simenon adopted the same method two decades earlier. Sometimes, as if to reinforce that drive towards the immediacy of drama and dialogue, he writes like a stage director giving notes to his actors.(Maigret at Picratt’s)

In what happened next, everything mattered: the words, the silences, the looks they gave one another, even the involuntary twitch of a muscle. Everything had great meaning and there was a sense that behind the actors in these scenes loomed an invisible pall of fear.Much of Simenon’s literary power, of the feeling and insight beneath his surface simplicity, can be glimpsed in those two sentences. They show how clever the trick was that he played in the Maigret books: to remain always within the policier genre, and simultaneously to transcend it. That is why, in 2003, Pléiade editions – strictly reserved for the classiest writers – included six Maigrets among their choice of Simenon’s works. It is also why Penguin Books have issued the totality of Maigret novels in new translations, to the great benefit of English readers everywhere.(The Hanged Man of Saint-Pholien)

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 80 © Robin Blake 2023

About the contributor

In terms of his work-rate Robin Blake is more like Maigret than Simenon, having written a mere nine crime mysteries featuring the eighteenth-century Lancashire Coroner Titus Cragg and his associate Dr Luke Fidelis