I was on a much-rehearsed trawl of the labyrinthine bookshop when I spotted it. A neat green-cloth country volume of the type churned out in their thousands in the 1940s and ’50s – years of hardship but also ones of optimism and dreams of a better future. I read the faded spine. A House in the Country by Ruth Adam, published by the Country Book Club, 1957.

Now this is the kind of thing I like. My bookshelves sag under the collective weight of H. J. Massingham, Adrian Bell, Ronald Blythe and Cecil Torr, but Ruth Adam was new to me. ‘This is a cautionary tale, and true,’ the book begins:

Never fall in love with a house. The one we fell in love with wasn’t even ours. If she had been, she would have ruined us just the same. We found out some things about her afterwards, among them what she did to that poor old parson, back in the eighteen- seventies. If we had found them out earlier . . . ? It wouldn’t have made any difference. We were in that maudlin state when reasonable argument is quite useless. Our old parents tried it. We wouldn’t listen. ‘If you could only see her,’ we said.

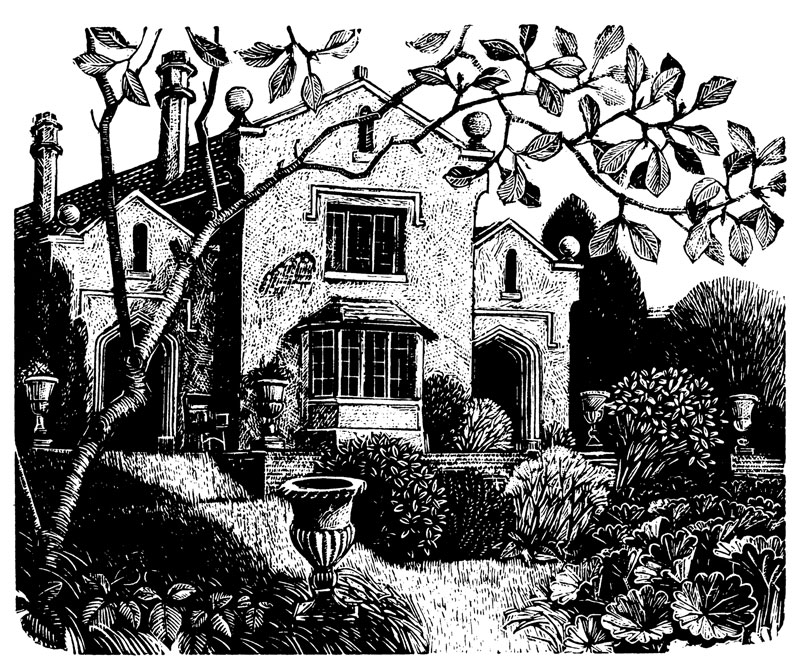

As the Second World War draws to a close, a group of six friends pool resources in order to rent a sizeable House in the Country – capital H, capital C. Their list of requirements is exacting. It has to be ‘one of those houses that’s been built bit by bit, for hundreds of years’. It has to have acres of land and dozens of outhouses. As it turns out, such a house does exist, a pretty, rambling but rather rundown Tudor manor house in deepest Kent. And so they move in.

Adam’s gentle, witty and compelling story is peopled by many memorable characters, especially old Howard, the gardener and general factotum. He had been with the old colonel, the manor’s late owner, since he was a pageboy in buttons, and he is the beating heart of the place, its wily and loyal retainer.

The colonel had a daughter, and it isn

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign in orI was on a much-rehearsed trawl of the labyrinthine bookshop when I spotted it. A neat green-cloth country volume of the type churned out in their thousands in the 1940s and ’50s – years of hardship but also ones of optimism and dreams of a better future. I read the faded spine. A House in the Country by Ruth Adam, published by the Country Book Club, 1957.

Now this is the kind of thing I like. My bookshelves sag under the collective weight of H. J. Massingham, Adrian Bell, Ronald Blythe and Cecil Torr, but Ruth Adam was new to me. ‘This is a cautionary tale, and true,’ the book begins:Never fall in love with a house. The one we fell in love with wasn’t even ours. If she had been, she would have ruined us just the same. We found out some things about her afterwards, among them what she did to that poor old parson, back in the eighteen- seventies. If we had found them out earlier . . . ? It wouldn’t have made any difference. We were in that maudlin state when reasonable argument is quite useless. Our old parents tried it. We wouldn’t listen. ‘If you could only see her,’ we said.As the Second World War draws to a close, a group of six friends pool resources in order to rent a sizeable House in the Country – capital H, capital C. Their list of requirements is exacting. It has to be ‘one of those houses that’s been built bit by bit, for hundreds of years’. It has to have acres of land and dozens of outhouses. As it turns out, such a house does exist, a pretty, rambling but rather rundown Tudor manor house in deepest Kent. And so they move in. Adam’s gentle, witty and compelling story is peopled by many memorable characters, especially old Howard, the gardener and general factotum. He had been with the old colonel, the manor’s late owner, since he was a pageboy in buttons, and he is the beating heart of the place, its wily and loyal retainer. The colonel had a daughter, and it isn’t long before she asserts herself, albeit from a distance. Howard brings bad news: the refrigerator in the kitchen doesn’t belong to the house at all – the colonel gave it to her before he died and now she wants it back. That is just the beginning:

‘Those fire extinguishers,’ said Howard, a few days later. ‘She couldn’t understand why those had been left for you. It seems she had some arrangement with the colonel about them.’A large area of linoleum follows suit, and the colonel’s daughter even lays claim to the Cox’s apple trees that Howard had previously told Adam were the best in the entire garden. Predictably enough, the adjustment from town to country is anything but smooth, and I love the way in which Adam nibbles away at the friends’ collective dream, steadily eroding it as the book progresses. They are still settling in when the vicar calls:

‘I’m afraid you’ll find the parishioners an undesirable collection on the whole,’ he said. ‘It’s a queer parish, very. I only took it because the last man didn’t like flying bombs and asked me to exchange. But since I’ve come here, I’ve wondered if he was deceiving me and that it wasn’t the flying bombs he minded. I should advise you very strongly to steer clear of the policeman. He’s a very queer chap indeed. However, I expect the authorities will find him out before long.’A few days later there is another knock at the door. It is the policeman.

He was young and extremely handsome and rather public school. ‘Natives are a rum lot,’ he said. ‘I’ve had to set the young chaps on slave labour, building themselves a club, to get the place under control. Remind me to show you over some time.’Various neighbours and interlopers turn out to have arcane and often inconvenient rights of access or storage. A farmer keeps all his harrows, tractors, hay-carts and bits of harvester in the outbuildings. A mysterious man in a bowler hat walks up and down the drive to a cottage in the grounds without ever saying a word to anyone. And there are other puzzling encounters.

One day, there were three men standing knee deep in the river. They wished me good morning as I went by. Later on, I found them cutting down a tree and thought this was pressing hospitality too far. ‘There’s nothing you can do,’ said Howard when I found him. ‘They got a right to do anything at all they like. They’re the Kent Catchment Board.’Howard is, however, getting tired. He complains that the garden is becoming too much for him, and places most of the blame at the door of the Americans, claiming that the dropping of the atom bomb has altered the weather and skewed the seasons to such an extent he can no longer keep up. When he eventually says he is going to give up altogether, the friends are devastated:

We felt the bottom had dropped out of our world. It was not only that Howard could cope with every emergency. There was something more important than that. It was Howard who had been our essential link with the past. He had taught us to understand the way the machinery of the great house and garden worked . . . We tried to imagine running the manor without Howard. It was impossible.The inevitable happens. Howard, whose world is contracting around him, is on the threshold of his final illness, and although arrangements are made to keep things running with the help of two younger men from the village, the die is cast. Adam is the keenest and often most touching of observers. Here is her description of Howard’s passing:

Twice every day I called at the cottage to ask how he was. I would hear her slow, heavy footsteps painfully descending the narrow stairs. When she at last reached the door and opened it, she was speechless and panting for breath. One day, I could not bear to fetch her struggling down again, and decided that my inquiry was more trouble to her than it was worth. I got as far as the stable yard and turned back. Howard died that evening. ‘He kept on asking for you,’ the old wife said without reproach. ‘I said – “She’s sure to call in to inquire, like she always does, and then I’ll ask her if she’ll kindly step upstairs for a chat.”’ Even at this distance of time, I remember the lilacs heavy with rain and the cuckoo calling mournfully, as I went back up through the garden. It taught me one lesson for life – when in doubt, always make your gesture. The risk of being a nuisance is the lesser one.The friends never really recover from this blow. After several years, and in light of experience, they go their separate ways, having had enough of their communal countryside experiment. After all, as Sartre said, ‘Hell is other people.’

*

A vicar’s daughter, Ruth Adam was born Ruth King in Arnold, Nottinghamshire, in December 1907. After attending boardingschool in Derbyshire, she was plunged into the grime and poverty of Nottingham’s mining villages, where she worked as a teacher. In 1932 she married Kenneth Adam, then a journalist on the Manchester Guardian but who later rose to become the BBC’s Director of Television. The couple had three sons and one daughter. Adam moved from teaching into writing, and her work – be it novels (she wrote twelve of them), radio scripts for Woman’s Hour, social commentary or journalism – had a strong feminist theme running through it. She worked for the Ministry of Information during the war, wrote the women’s page for the Church of England Newspaper from 1944 to 1976, and even produced comic strips in Girl magazine, launched in 1951, creating a number of strong female characters who were independent-minded and resourceful. Perhaps her best-known work is A Woman’s Place, a polemic challenge to male chauvinism, and a world away from A House in the Country. She died on 3 February 1977 in London at the age of 69. So was A House in the Country, with all its charm and insight, fact or fiction? As with that great country chronicler, S. L. Bensusan (SF no. 41), the answer is probably a bit of both, but the result is tender and genuine.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 57 © Anthony Longden 2018

About the contributor

Anthony Longden is a freelance journalist and a specialist partner at a crisishandling firm. He is fighting a losing – and frankly half-hearted – battle against a steadily rising tide of books that threatens to engulf his home.