Nicholas Fisk (1923–2016) is a half-forgotten name now, and his memoir Pig Ignorant is a wholly forgotten book. It deserves not to be, and he deserves not to be. Fisk was a bestselling children’s writer through my own ’70s and ’80s childhood and was described by one critic as ‘the Huxley-Wyndham-Golding of children’s literature’. But if he is remembered now, it’s for his science fiction and only vaguely, and only by people about my age. There’s the Bradburyesque alien invasion horror Grinny (see SF no.78) and its sequel You Remember Me, the disconcerting genetic-engineering story A Rag, a Bone and a Hank of Hair, and Trillions, in which tiny, collectively intelligent alien particles fall to earth like snow. In his most memorable stories the surface appearance of the world masks something darker and stranger. There’s a world behind the world.

Accordingly, perhaps, this remarkable short memoir is a journey from innocence to experience. Its themes are the big ones: sex and death. And its focus is on the narrow little sliver of time that takes its protagonist from his mid-teens to the brink of manhood proper. Its epigraph is from Victoria Wood: ‘I believe we all have a certain time in our lives that we’re good at. I wasn’t good at being a child.’ The book, written half a century after the events it describes, traces Fisk’s attempt to leave his childhood and find a secure identity as a young adult: ‘For Nick, school is over! He’s free! He’s his real self at last!’

But who is that real self? The very framing of the narrative is a little unstable. Like Frances Hodgson Burnett – an earlier children’s writer who in The One I Knew the Best of All also produced an extraordinarily vivid memoir of childhood (that sort of recall seems to be a characteristic of children’s writers) – Fisk describes his younger self in the third person. And his protagonist is ‘Nick’: another little estrangement. Fisk’s real name was David Higginbottom. The narrator self introduces us to his adolescent self as ‘a walking, talking, breathing solid ghost. Not the ghost of someone dead. I am still alive. His flesh is my flesh, his heartbeat is my heartbeat. Because he is me. But so long ago . . .’

This Nick both is and is not the boy jeered at by bullies as ‘Muvver’s darling’. A flashback within the first couple of pages sees him disturbed at the sight of a pack of delivery-boys on bicycles: ‘Nick’s had trouble with errand-boys.’ (The real-life encounter with bullies on bicycles had already found its way, lightly fictionalized, into Fisk’s 1979 novel Monster Maker.) ‘But that happened years and years ago, when he was twelve or thirteen. Just a kid. He’s not a kid anymore. I mean, just look at him!’

He’s sixteen and a half. He’s about six feet tall, fair-haired, ginger-jacketed, grey-trousered, pink-faced. He parts his hair right over on one side, which gives him a schoolboyish look. He bites his nails but will soon give up that schoolboy habit.

Look, too, at the world around him, a London suburb in 1939, fully furnished, exactly remembered:

A car is stopping outside No. 44, where his friend Peter lives. A Sunbeam saloon with a fawn body, black wings and a golden polished-brass radiator. Lucky old Peter, having a Pa with a car. Not many people have cars. The streets belong to errand-boys, cats and dogs, horse-drawn milk-floats, lorries delivering Corona soft drinks, postmen with conical hats peaked in front and behind, and ‘Wallsie’, the Walls Ice-Cream man pedalling his freezer-box trike.

Nick’s progress through the book takes him out of his sheltered middle-class comfort zone, just as it takes him out of his childhood self. We move into Soho and the centre of town and as the story advances so too does the Blitz. Here is a bomb-damaged Burtons, the men’s outfitters: ‘drunken mannequins in torn suits with broken glass on their shoulders’. There is Boots the chemist: ‘All that remains of Boots is the word BOO, in that familiar curly script, and even that is being kicked aside by tired Rescue Squad and demolition men.’

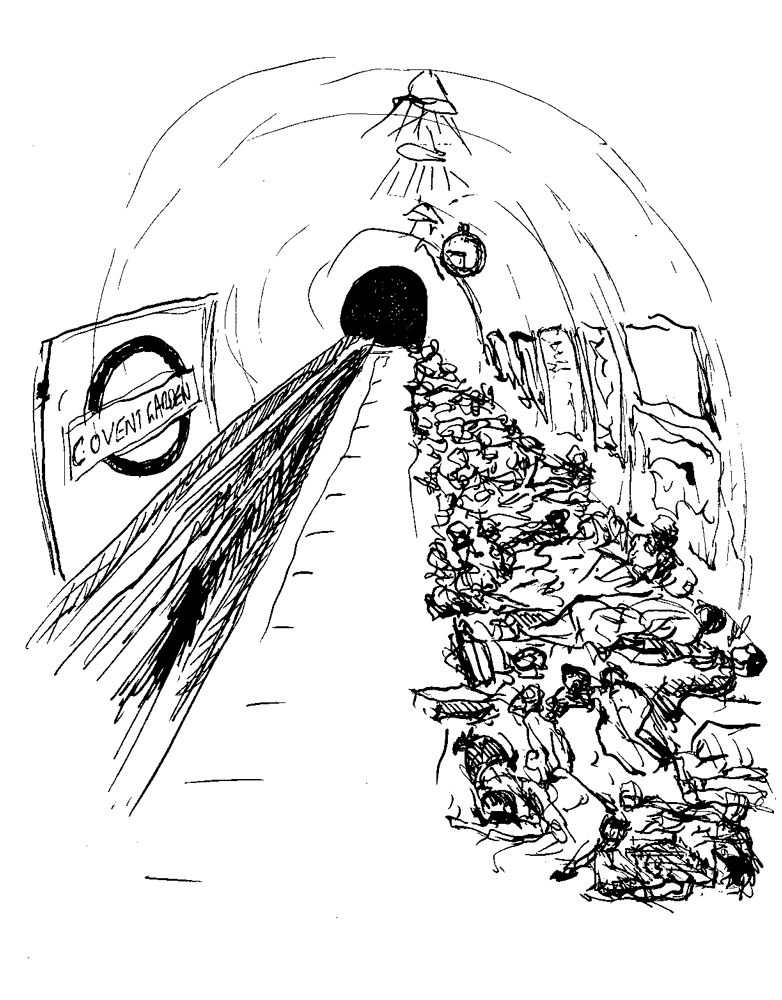

He describes sheltering at home with the family, bickering over board games: ‘Nick, his sister, his mother and Uncle Rob, together in the candlelit gloom, breathing in coal dust and the cosy fumes of the Valor oil stove . . . Outside is the clamped-down dark of the black-out, always unfamiliar and surprising.’ He evokes the boredom and anxiety and disgust of the public shelters (‘smell of urine and unwashed clothes and bodies’) and Underground stations (‘Smells, lice, feet treading on your face, sudden screeches and shouts as quarrels break out, a child being sick . . . tangled knots of bodies under the cheery posters on the tiled walls’).

We meet, later on, a wartime Brighton which, like the layered palimpsest of the child-Nick-in-teenage-Nick-in-adult-Nick, is a ghost of itself, ‘joyless and tatty now. No Max Miller (‘That’s a nasty cough, Lady! Chesty! You want to rub it, Lady, give it a good rub! ’Ere, Vick!’), no deck chairs filled with sweaty mums and dads, no Brighton Rock, no bum-and-bosom naughty postcards, nothing very much.’ In the Royal Pavilion, ‘the mock-Chinese furnishings, the oriental gilded ceilings, the domes and hanging dragons, fading and dusty: exotic draperies have fallen in swathes; the enormous banqueting table is laid with two tea mugs and a month-old newspaper.’

So, Nick is becoming an adult even as the world around him changes, and the furniture of his proto-adult identity is unstable. He affects to smoke a pipe because a girl he fancies doesn’t like men who smoke cigarettes. He gets a job as a receptionist and typist at a theatrical agent’s. He finds his shy, faltering way into the jazz clubs where he would come to moonlight as a guitarist. He becomes an initiate in different worlds which overlap incompletely. There are the smoky jazz clubs in which he plays guitar, to which he wins entry after a chance encounter with a drummer. There’s the start of his writing career (he places an article on Amelia Bloomer, inventor of the titular underwear), midwifed by writer friends of his parents. There’s his worm’s-eye view of the theatrical and publishing worlds. There’s his work as a probationary Meteorological Officer, collating data from airfields and sending hydrogen balloons aloft to test the wind, as he fills the gap between civilian life and his call-up.

Each time he learns a new language – hepcat talk in the jazz clubs; music-hall songs among the post-room ladies at the publisher (‘They know a thousand songs, all old. He teaches them only one new one – Who Put the Benzedrine in Mrs Murphy’s Ovaltine? – and glows with pride in their acceptance of it’); the swaggering lightness of the RAF fliers for whom ‘heroics are reserved for the unheroic’, so that ‘bought it’ means died, but ‘shot down in flames’ means romantic difficulties. He’s changing selves, but ‘someone else, never himself, gets him going. There always has to be an O’Leary acting as his starter motor.’ The reference is to ‘O’Leary Says’ (the game we know as ‘Simon Says’): it’s telling, perhaps, that the metaphor he uses is from a child- ren’s game.

Sexual initiation too – in which, as ever with Nick, it’s the women who are usually O’Leary – is subject to ‘the Rules of the Game’. This is, as our narrator reminds us from the early 1990s, a time before the Pill. Women are idealized, impossible to understand and sexually dementing. The young Nick, and the prose that describes his life, is radioactive with adolescent lust: ‘Then she’s walking away, with her pleated skirt caressing her springy tapered calves and her right breast lifting and bouncing as she turns to wave’; ‘Just look at her! The red of her lips, the flash of her eyes, the roll of her hips, the curve of her thighs (Nick often finds himself thinking in bad verse)’; ‘red-nailed hands over her whipped-cream bosom’. Our hero is, often, red-faced, stammering, surprised and grateful when women yield, jealous and disillusioned when they yield to other men.

And then, death. The war is in the background of this story, and then in the foreground. The narrator reiterates Nick’s sense – a very childlike sense – that the German bomber pilots are so alien to him as to occupy a different world. The bombs may fall; but they won’t fall on him. He’s immune. ‘You or he or she may be killed, but I won’t be.’ His older sister, called up to the Wrens, is posted to a naval base under frequent German attack: ‘He feels almost impatient with his mother’s anxiety.’

In the dawn hours, Nick sort-of-rescues an apparently drug-dazed girl from the aggressive sexual attentions of a drunk, walks her back home, and finds her house freshly bombed out, her family dead. She unhooks a birdcage from the intact curtain rail:

‘Vvvp-vvp!’ she says, her head on one side, her pursed mouth smiling. ‘Who’s a lovely boy, den? Ess, oo are! My Tinker!’ The bird lies dead on the sandy floor of the cage. Its little legs stick out like twigs. The girl beams at it.

An open question is how the visceral experience of violence close up connects to the abstract understanding of violence as a condition of history. This short book is punctuated by unanchored vignettes of violence at a personal level. Nick witnesses a bar fight: ‘something glints and a girl screams “A-oww!” and blood squirts on to the dingy paintwork of the wall and Mrs Jack sails in with a parrot screech and a flailing dishcloth’. It’s a cut-throat razor. Nick is punched in the face when he gets between a jazz player and his mistress. He chances on an organized fight on Brighton beach at night and, after it disperses, is sick over the promenade railings. ‘That was evil. The real thing. The genuine article . . . But a thousand-bomber raid is different because War is different. Isn’t it?’

Is it? Nick is strafed by a Messerschmitt at an airfield. The episode is described with extraordinary detachment: ‘That is when he sees the effect of bullets on wet earth. Soil and grass lift and pucker. He thinks of his mother’s sewing machine.’ The family home is nearly struck by a bomb. And, perhaps most indelibly, in one image early on in the aftermath of an air-raid, Fisk and a warden find someone half-buried in the rubble:

It is an elderly man, very thin, wearing a sort of striped waistcoat. The ghastly face is masked in plaster dust. A butler? ‘There you are, mate, coming along nicely, soon have you out, you’re all right.’

But the man is not all right. There is only the upper half of him left . . . Shiny wet tubing . . .

As the passages I quote here will, I hope, make clear, Fisk is at his best a formidably good writer. This little book is no doubt a valuable resource for the social historian, full as it is of the atmosphere and attitudes, the brand names and idioms, the jumbled lyrics of vulgar songs, of wartime England. But it’s more than that.

Fisk’s eye for the disconcerting but memorable detail, his cool self-examination and layered sense of the in-between psychology of adolescence, and his jazz-guitarist’s feel for rhythm in sentences and sound-effects, makes it a literary artefact as well as a historical one. It describes the making of a man, but also the making of a writer. It ends with Nick, called up at last, enmeshed in the mind-numbing routines of RAF basic training:

Nick has never been near a kite. He knows nothing of aircraft engines, cockpit layouts, armament and a million other things. These may come later. Meanwhile, caught in the machine, he is resigned to pig ignorance. Only five per cent of his own being remains, in the form of bent and frayed books stuck in his kitbag, some old photographs, some new friends. Pig ignorant. But like it or not, he is learning.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 80 © Sam Leith 2023

About the contributor

Sam Leith is Literary Editor of the Spectator and the author of You Talkin’ to Me? Rhetoric from Aristotle to Trump and Write to the Point: How to Be Clear, Correct and Persuasive on the Page. His book on the history of children’s writing, The Haunted Wood, will be published in 2024.