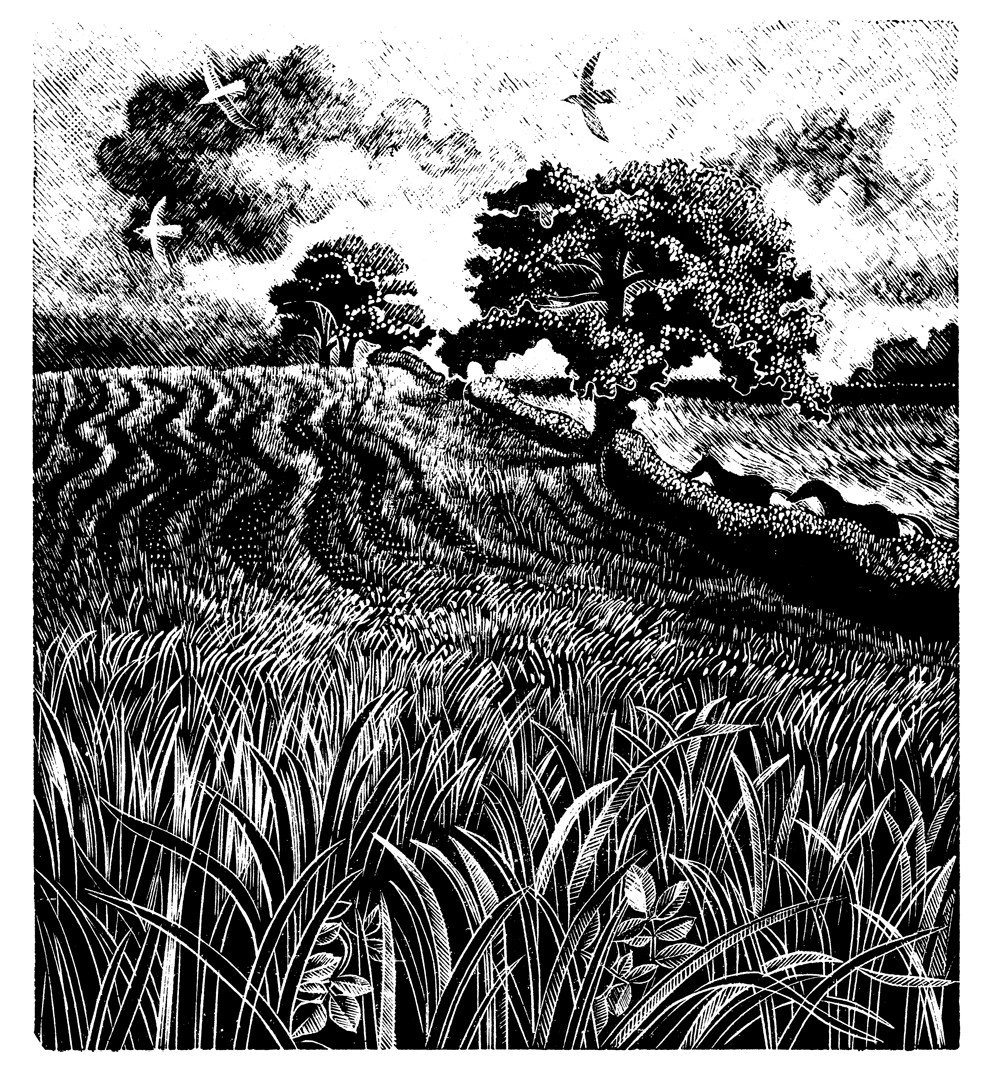

Early one morning, late in July, the villagers of ‘crack-brained Brensham’ woke to a remarkable spectacle. There amid the customary colours of furze and wheat was a seven-acre field that ‘had suddenly become tinctured with the colour of Mediterranean skies’. Nothing like it had ever happened before, so that the villagers caught their breath at the sight of this miracle: a great, vivid patch of cerulean ‘so clear and pure that it made one think of eyes or skies’.

There could be no doubt who was responsible for this act of rebellion: William Hart, who – against the directives of government authorities, and in defiance of the farmer’s ordinary seasonal rotations – had planted a field of linseed. ‘“Have you seen old William’s field?” people said. “It does your heart good to look at it; but Lord, I wouldn’t be in his shoes when the trouble starts!”’

The Blue Field is the last in John Moore’s trilogy which pays tribute to an England that seems, somehow, both absolutely familiar and impossibly remote. I first encountered Brensham during an arduous recovery from illness. A lifelong walker and seeker-out of hidden places, I was unable to wander much more than ten minutes from home, but to read John Moore was to be transported instantly away from the dreariness of recuperation to a fragrant field in high summer.

If the first two books of the trilogy are portraits of places – Elmbury, a proxy for Tewkesbury, Moore’s birthplace; and Brensham, an amalgam of nearby villages – The Blue Field is largely a portrait of a man:

I am going to tell you the story of a man of Brensham who was so wild and intractable and turbulent that he failed, in the end, to come to terms with our orderly world (or perhaps one could say that our orderly world had failed to come to terms with him).

This wild, intractable, turbulent man is William Hart, farmer of the blue field: descendant, so he insists, of Shakespeare himself; vast as an oak; hot-tempered and gentle; a roisterer, brawler and tamer of foxes; sower of wild oats across the county, and possessed of a genius for contriving strong drink out of everything from a parsnip to a pea-pod. Hart, we suspect, did not exist – or at any rate, not quite: Moore frankly confessed to ‘playing fast-and-loose with chronology and topography’, and preserved the privacy of his subjects by changing their names. And yet the reader is left with little doubt that here is a portrait as accurate and acute as if captured by digital camera, not merely of a man, but of a kind of Englishness.

The reader follows Hart through his boisterous, untamed youth, which is all love affairs and brawls; through various stand-offs with the authorities and with those who would consider themselves his betters; to Moore’s last glimpse of him, his face ‘brown as shoe leather and wrinkled as a russet apple in the New Year’. Moore’s prose is so lively, and he is so attentive to dialect and foible, that William Hart erupts into the room as the pages are turned, trailing in his wake the scent of bee-orchids and beer, and the sound of Land Girls preparing for an evening’s dance.

Moore was a pioneer conservationist, but his subject here is not this ancient hedgerow or that threatened garden bird, but rather the human animal and its habitat. Incidents in Hart’s life – reported with Moore’s distinctive, stylish blend of erudition, wit and bosky atmosphere – are attended by a vivid and varied cast in the tradition of Eliot, Dickens and Shakespeare. There is Mr Chorlton, the retired schoolmaster, and his friend Sir Gerald, who came home from a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp wizened in body, but not in spirit; there are the rascally Bardolph, Pistol and Nym, who behave in every respect like their Shakespearean namesakes; there is Mrs Halliday, wife of the Labour MP, a ‘very intelligent young woman’ who understands instinctively that she will fit ‘into the jigsaw-puzzle’ of Brensham’s little world.

The desultory reader may perhaps consider Moore a sentimentalist (after all, he referred to his own novels as ‘country contentments’). But there is something clear-eyed and direct in his portrait of Brensham which recalls John Berger’s portrait of a rural country doctor, A Fortunate Man. It is, above all, an act of witness, though Moore speaks from within the village: he writes not of ‘them’, but of ‘us’, and can recognize a sprout-picker at twenty paces by the shape of their bottom as they stoop over the frozen fields.

The Blue Field was published in 1948, and marks a liminal time between war’s aftermath and the coming of modernity. Here are farmer’s boys who ‘flew as tail-gunners through the fiery night above Berlin’, and here is George Daniels, who has not taken off his paratrooper’s jacket since he landed in Normandy on D-Day (Moore himself was present at D-Day as a press attaché, and one can’t help but wonder if he, too, clung on to some sartorial remnant of the war). But here also is the Syndicate, a sinister collection of would-be developers, entrepreneurs and out-of-towners, taking over the moth-eaten home of the local squire; here is a Labour MP, newly installed with his visionary wife, forever raising questions in Parliament as to the villagers’ habits of sanitation, parenting and farm husbandry. What Moore brings to Brensham is nothing so saccharine as sentiment, but rather a fond compassionate gaze. When he writes, as he does often and with a kind wit, of soft-eyed Pru Hart, ‘the naughtiest girl in Brensham’, who cannot be kept indoors at night, but rather wanders the fields at dusk seeking out lovers (in due course doing so with prams full of her offspring), he does so without either judgement or prurient glee. He seems to say: we have always been like this, and always shall be, and there is nothing wrong with that.

If the book is in some respects a museum piece, it has by no means gathered dust. Now and then something startles the reader in its immediacy and contemporaneity, such as William’s horror at the local fox hunt, in which he seems not some smocked yokel in a Constable painting, but a progressive who would sit well among twenty-first-century hunt saboteurs, so long as strong beer was supplied. When Moore turns his pen to the local gypsies, who have forsaken their ancestors’ wandering ways and taken up residence on the outskirts of Brensham, the reader may prepare an anticipatory wince at any forthcoming infelicities with regard to minorities, but Moore writes of them with precisely the same benevolent amusement with which he writes of the English farm boys or their sprout-picking paramours:

Life has always been hard for them, and now that our own high standard of living is dwindling fast, and the cold winds of the world are blowing one by one our precious amenities away, they might laugh at our discomfiture and our grumbling – if they ever troubled themselves enough about our affairs to be amused by them.

Indeed, the reader may be struck by how Brensham embraces the Polish Count Pniack, who marries a local girl and is forever trying to explain the pronunciation of his name (‘The P is silent!’); and by how the gypsies represent, for Moore, qualities of English life which are threatened by the first inklings of globalization (‘I don’t mind betting that their hens will still be scratching about under their caravans when our last dollar has bought the last packet of dried eggs from America!’). The villains of the book are interlopers not on national grounds, but on ideological ones – not least the Syndicate:

The village passionately hated them, and there was an element of fear in the hatred, for it really looked at one time as if the Syndicate would overwhelm Brensham and impose their shabby get-rich-quick regime upon it, tyrannize and subdue and cheapen and emasculate it, and turn it at last into a tributary province of their far-flung financial empire.

What it is to be English has always been a contentious and largely unanswerable question, demanding reference to so many contributing cultures that one thinks instinctively of Daniel Defoe’s line that the English are ‘a mongrel race’. To read The Blue Field is to see everything about Englishness that is universal and common (a Brensham lad wrote home during the war: ‘The [French] are very good farmers. They drink cider. If they didn’t speak Frog they’d be just like us. It makes you think.’), but also to recognize, with a kind of nostalgic calling on half-forgotten memory, an Englishness that cannot easily be weaponized to malign political effect. It is the Englishness of parsnip wine drunk in imprudent quantities, and of devoting time to the cultivation and the eating of sprouts; of grudges nursed in unspoken silence, until the matter can only be settled with fists; of diffident offers of friendship, and of lust in the fields in midsummer, when there’s little else to be getting on with; of squires in pink coats bawling at truculent villagers who favour foxes above the aristocracy, and impecunious lords giving their last shilling to young mothers while the roof of their stately home rots about their noble ears. Perhaps most of all, it is the very particular Englishness of rebelling – in however small, petty or impotent a fashion – against rules and regulations impinging on individual liberty, even ‘when the trouble starts’: of a single field of linseed in full bloom, flown like a blue silk flag at the foot of Brensham Hill.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 58 © Sarah Perry 2018

About the contributor

Sarah Perry is the author of The Essex Serpent (2017), and is fond of parsnip wine. Her second novel, Melmoth, was published in 2018.