In the summer of 1933, after leaving the Royal Academy Schools where one of his paintings had just been accepted for the Summer Exhibition, my father Mervyn Peake abandoned London for Sark in the Channel Islands. The move followed a recommendation from his former English teacher who suggested, with my father in mind, that ‘the possibilities were unusually rich for artists with a keen sense of things firmly rooted in primitive nature’. The two years he then spent on the island were so idyllic that shortly after the war he decided to return, this time with his family.

The very first voyage we made was wonderful. Off the island of Jethou, midway between Guernsey and Sark, a school of porpoises suddenly made their presence known, gliding beside our boat, the Ile de Sercq, slicing the translucent water just beneath the surface. The porpoises accompanied us most of the way between the islands, and we passengers were transfixed by their speed and elegance. Then in an instant the sleek mammals disappeared, veering off north towards the French coast.

The island of Sark remains the locus for many vivid memories I associate with having had such an unusual father. Decades on, some remain as wide-eyed provoking reminders of him not as mortal father so much as supernatural being, elevating the man way beyond the quotidian. Sometimes, unencumbered by conventional behaviour or any yardstick set by the ordinary, he emitted an almost disembodied energy and bravado, satisfying both the daredevil in him and wonder in the recipient of his ideas.

During the winter of 1947, the coldest on record, when the boat between Guernsey and Sark failed to make the crossing for over three months, and with electricity yet to be installed in our home, true Arctic conditions prevailed. It was during this terrible winter that I became vaguely aware of a gradual accumulation of biscuit tins in the freezing house.

One morning, when it was still quite dark outside, and ice on the frozen window panes adhered like tiny jagged lightning-strikes to the glass, my father knocked

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIn the summer of 1933, after leaving the Royal Academy Schools where one of his paintings had just been accepted for the Summer Exhibition, my father Mervyn Peake abandoned London for Sark in the Channel Islands. The move followed a recommendation from his former English teacher who suggested, with my father in mind, that ‘the possibilities were unusually rich for artists with a keen sense of things firmly rooted in primitive nature’. The two years he then spent on the island were so idyllic that shortly after the war he decided to return, this time with his family.

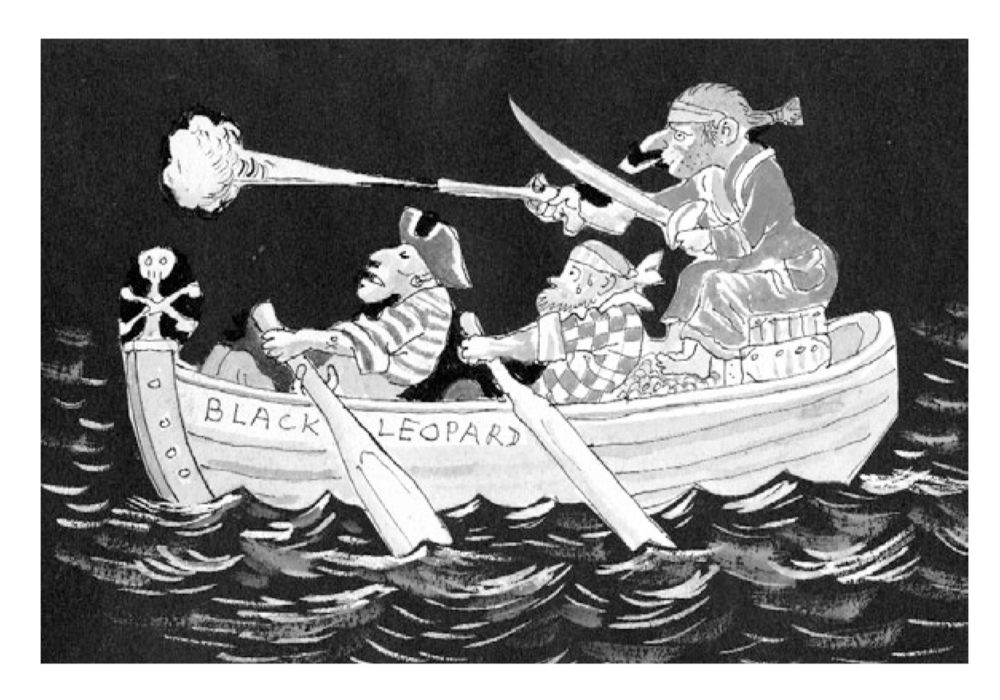

The very first voyage we made was wonderful. Off the island of Jethou, midway between Guernsey and Sark, a school of porpoises suddenly made their presence known, gliding beside our boat, the Ile de Sercq, slicing the translucent water just beneath the surface. The porpoises accompanied us most of the way between the islands, and we passengers were transfixed by their speed and elegance. Then in an instant the sleek mammals disappeared, veering off north towards the French coast. The island of Sark remains the locus for many vivid memories I associate with having had such an unusual father. Decades on, some remain as wide-eyed provoking reminders of him not as mortal father so much as supernatural being, elevating the man way beyond the quotidian. Sometimes, unencumbered by conventional behaviour or any yardstick set by the ordinary, he emitted an almost disembodied energy and bravado, satisfying both the daredevil in him and wonder in the recipient of his ideas. During the winter of 1947, the coldest on record, when the boat between Guernsey and Sark failed to make the crossing for over three months, and with electricity yet to be installed in our home, true Arctic conditions prevailed. It was during this terrible winter that I became vaguely aware of a gradual accumulation of biscuit tins in the freezing house. One morning, when it was still quite dark outside, and ice on the frozen window panes adhered like tiny jagged lightning-strikes to the glass, my father knocked quietly at the bedroom door where my brother and I were sleeping. Suggesting that we wrap up warmly and follow him downstairs, he said he had something very special to show us. Dressing quickly we rushed down and into the garden, treading through the thick snow behind him. We rounded one end of the large house and there, looming like a white mirage in front of us, was the most wonderful of sights – a full-sized igloo. ‘How did you make it, Dad?’ we asked incredulously. ‘It’s a real igloo, just like an Eskimo’s.’ ‘But there’s someone in there!’ we shrieked, half-scared, half-fascinated, as from a deliberately missing block an Eskimo grinned out at us. Now I understood why the biscuit tins had been accumulated – they were the ideal moulds for shaping blocks of compacted snow for the construction of a perfectly rounded house, flawless in its symmetry. We hesitated before following our father down the tunnel and into the body of the igloo. Once inside, however, we discovered not only that the Eskimo was in fact an alarmingly realistic painting, but also that the interior was wonderfully warm. Blankets covered the entire floor area, and on top of them had been laid some drawings of Eskimo life. Huskies pulled sleds, walruses lolled on the ice, and hunters held aloft harpoons, the men perfectly captured in the act of launching them into the deep. Sark was also the setting for my father’s novel Mr Pye, published in 1953, in which the eponymous hero attempts to convert the islanders to love. ‘Just the right size,’ says Mr Pye on his arrival from Guernsey, ‘it will do very nicely.’ Perhaps my father’s upbringing as the son of a medical missionary in China and, later, his fondness for the island influenced the book, in which we find Tintagieu the local tart speaking in broad Sarkese, while before an impressionable Mr Pye, the hopeless artist Thorpe defends his craft against ‘amateurs, Philistines, and racketeers’. Most of Gormenghast was also written on Sark. When it was cold my father, Proust-like, would often write in bed. In summer he would either sit in the house in an armchair, a drawing-board across its arms, or in the light and airy surroundings of the large conservatory. It was here, usually on a Sunday morning as my mother was preparing lunch, that he would produce drawings for my brother and me. Sometimes in pen, sometimes in wash, occasionally in pencil, they were drawn directly on to the pages of our small but identical black snapshot albums, and these soon became filled with the most magical of images: Red Indians, pirates, animals, clowns and the strangest of strange creatures, all visual reminders of the happiest days of my life when an atmosphere of total freedom reigned both at home and on the island. Looking now at the colourful pages in my own fragile book, I am immediately transported back to that moment in the conservatory when blood-stained cutlasses emerged from the page, or the vicious-looking captain of the Black Leopard appeared firing a pistol over the heads of his scar-faced crew. Pirates predominated, while desert islands often formed a background to the pictures, with scenes of tropical plenty a constant leitmotif. As the drawings took shape, I became totally immersed in the world my father was creating. I too was marooned. I was there on the golden beaches with these wild buccaneers. With them, I plotted under the coconut palms. I was one of them.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 12 © Sebastian Peake 2006

About the contributor

In 2006 Sebastian Peake celebrated thirty-five years in the wine trade and over twenty speaking about Mervyn Peake at literary festivals, bookshops and English departments both at home and abroad. His memoir A Child of Bliss describes what it was like to have had an eclectic genius for a father.