There’s a wooden ruler in our kitchen drawer that lists the Kings and Queens of England. On first glance, it seems a rather joyless kind of museum trip souvenir: a functional, varnished column of first names, Roman numerals and dates. But there is one touch that makes me very fond of it. Embossed on the end are the words: ‘British History Rulers’. Someone, somewhere in the company that manufactures such earthing rods for pocket money, saw the gleam of a compensatory joke, and decided to make it.

1066 and All That is a book that for me gleams so strongly with the same spirit of redress as to be a work of satirical genius. This is, I know, a little stronger than the usual estimate of Sellar and Yeatman’s ‘humour classic’. Its phrases are still commonly cited, and it appears never to have been out of print since first published in 1930. (I own two copies, one from 1936 – already the twenty-second edition – and another from 1994, reprinted twice in that year.) Yet literary criticism has paid it hardly any tributes at all. Presumably, this is because a) it contains cartoons and b) its preferred modus operandi is the pun. The pun is sometimes said to be the lowest form of wit. There is another way of looking at it, though – not as the lowest, but the most levelling.

A pun collapses a semantic hierarchy by forcing two incongruous ideas together, for example, monarchs and metrics. As such, it is a small but permanent form of Peasants’ Revolt. The comic genius of 1066 and All That is to make one-off schoolboy witticisms about official English history into a miniature world – a sceptred isle of twelve-inch Rulers, destined to become ‘top nation’. But its moral genius is to regi

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThere’s a wooden ruler in our kitchen drawer that lists the Kings and Queens of England. On first glance, it seems a rather joyless kind of museum trip souvenir: a functional, varnished column of first names, Roman numerals and dates. But there is one touch that makes me very fond of it. Embossed on the end are the words: ‘British History Rulers’. Someone, somewhere in the company that manufactures such earthing rods for pocket money, saw the gleam of a compensatory joke, and decided to make it.

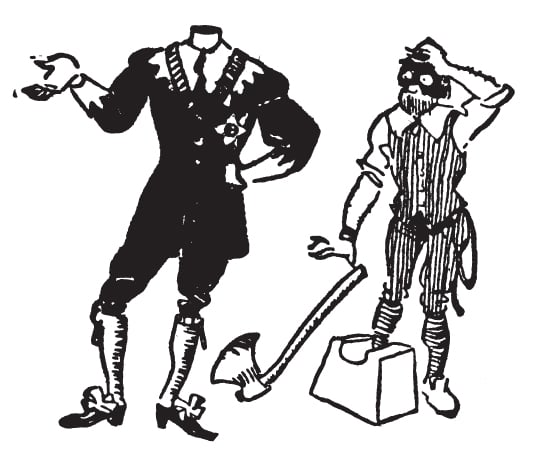

1066 and All That is a book that for me gleams so strongly with the same spirit of redress as to be a work of satirical genius. This is, I know, a little stronger than the usual estimate of Sellar and Yeatman’s ‘humour classic’. Its phrases are still commonly cited, and it appears never to have been out of print since first published in 1930. (I own two copies, one from 1936 – already the twenty-second edition – and another from 1994, reprinted twice in that year.) Yet literary criticism has paid it hardly any tributes at all. Presumably, this is because a) it contains cartoons and b) its preferred modus operandi is the pun. The pun is sometimes said to be the lowest form of wit. There is another way of looking at it, though – not as the lowest, but the most levelling. A pun collapses a semantic hierarchy by forcing two incongruous ideas together, for example, monarchs and metrics. As such, it is a small but permanent form of Peasants’ Revolt. The comic genius of 1066 and All That is to make one-off schoolboy witticisms about official English history into a miniature world – a sceptred isle of twelve-inch Rulers, destined to become ‘top nation’. But its moral genius is to register the way in which this world of Great Men leaves the little men out. ‘For Pheasant read Peasant, throughout’, warns the well-known opening Erratum. This is followed by an even grislier error: ‘For sausage, read hostage.’ Already, we are not far from Swift’s A Modest Proposal, in which children are considered as a source of meat for the Irish poor. That cold depth of irony is reached in the chapter on the Industrial Revolution, when, it is said, all the rich men in England simultaneously discoveredthat women and children could work for twenty-five hours a day in factories without many of them dying or becoming excessively deformed. This was known as the Industrial Revelation and completely changed the faces of the North of England.The casual violence of the final slip can only provoke what Wyndham Lewis called the tragic laughter of true satire. The bloodless black-and-white lines of John Reynolds’s original illustrations perfectly complement the dryness of the text. (The headless torso of Charles I holds forth foppishly to the crowd. Caption: ‘Very memorable’.) The humour of 1066 and All That is nothing like the slapstick of the current ‘Horrible Histories’ series. The idiotic ‘Editors’ are calmly unconcerned with conveying real information. History, as the ‘Compulsory Preface’ tells the reader, ‘is not what you thought. It is what you can remember.’ A modern reprint of the text that boasted ‘authentic contemporary illustrations’ – in other words, bits of the Bayeux Tapestry and illuminated manuscripts – missed the point entirely. I don’t remember the first time I read 1066 and All That as a child – only that it was my parents’ 1960s Penguin paperback copy, and sometime during the 1980s. What I do remember is appreciating it as an adult book. Its knowing humour reminded me of a great-aunt whose letters delighted in the same mock-solemn capitalizations as Sellar and Yeatman’s favourite judgement: ‘a Good Thing’. I enjoyed it, and one day I assumed that I would understand it. But today I still have the feeling that I am missing something on most pages. One of the pleasures of rereading is building up my stock of bagged jokes. Recently, for example, I realized why ‘the Charge of the Fire Brigade by Lord Tennyson and 599 other gallant men . . . advanced for a league and a half (41⁄2 miles)’. It is, of course, a literal totting up of Tennyson’s opening lines: ‘Half a league, half a league, / Half a league onward’. No doubt some of the book’s appeal has been lost now that history is not taught as recitation of ‘103 Good Things, 5 Bad Kings and 2 Genuine Dates’. It has been plausibly suggested that 1066 and All That was part of a wider reaction against grand narrative history, pioneered in 1918 by Marjorie and C. H. B. Quennell’s fine alternative primers, A History of Everyday Things in England, and still felt in my school days of dressing up as a medieval peasant or workhouse orphan. Sellars and Yeatman were small boys – and so prime targets – when H. E. Marshall’s patriotic bedtime book Our Island Story was published in 1905 (see Slightly Foxed, No. 9). Here, they take their revenge on its sentimental vignettes at every turn:

After the battle [‘of Boswell Field’] the crown was found hanging up in a hawthorn tree on top of a hill. This is memorable as being the only occasion on which the crown has been found after a battle hanging up in a hawthorn tree on top of a hill.But I also suspect that the speed and erudition with which 1066 and All That weaves its tissues of allusion – the result, perhaps, of collaborative composition by post – mean that even its earliest readers accepted a certain mystifying surfeit of wit as part of the book’s poetry. I’ve never known quite what agricultural trial-by-ordeal is confused in the image of a man plunging his head ‘into boiling ploughshares’. The molten surrealism is powerful enough. It is this quality, combined with their Swiftian insight, that makes me want to rescue Sellar and Yeatman from the Humour section and place them alongside the literary Modernists. Like Modernism’s experiments, their carnival wordplay was a response to the failure of nineteenth-century narratives after the First World War. Both men fought and were wounded in the war before meeting at Oxford as undergraduates. Yeatman in particular is reported to have been ‘perforated like a colander’. A pun can be a very stoical thing under such circumstances. Consider Mercutio’s dying words in Romeo and Juliet: ‘Ask for me tomorrow, and you shall find me a grave man.’ In 1066 and All That, the war is simply ‘The End of History’. The Modernism I most associate them with, however, is not the panoramic despair of T. S. Eliot in The Waste Land, but the everyday things and puns of James Joyce – the Irish exile who kept a picture of Cork in a cork frame and who quipped, through his alter ego Stephen Dedalus, that Bruno the ‘terrible heretic’ was ‘terribly burned’ (compare Sellar and Yeatman on medieval martyrdom: ‘many of the people who were burnt, bricked, tortured, etc., became quite otherworldly’). In Ulysses (1922), Joyce has Stephen say that ‘History . . . is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.’ But it is also his day job, the subject he teaches to boys who can only remember ‘There was a battle, sir.’ (Joyce has Dedalus glancing down at a textbook for the answer.) It’s possible that the well-read Sellar and Yeatman knew the scene. It’s also possible that the very well-read Joyce knew 1066 and All That when he was writing Finnegans Wake (1939), an epic of misremembered history founded on the kind of low pun that confounds kings with other things: ‘Alfred the Cake’ (1066 and All That); ‘William the Conk’ (Finnegans Wake). I hope so.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 16 © Jeremy Noel-Tod 2007

About the contributor

Jeremy Noel-Tod teaches the more memorable bits of English Literature at the University of Cambridge, and writes reviews for the Daily Telegraph and the Times Literary Supplement. He no longer dresses as a medieval peasant.