Nearly thirty years ago, I let down J. L. Carr, the novelist, and, as a result, regret grabs me by the throat every time I take down one of his books from the bookshelf. Reading A Day in Summer recently proved no exception.

This was his first novel, published in 1963 by Barrie and Rockliff, the tenth publisher to whom he sent it. I have a great affection for it, perhaps because so many of his preoccupations are already revealed: an amused, sympathetic fascination with small, self-contained communities; the inability of men and women to understand each other; the unnerving backwash of memory experienced by those who have fought in a war; the decline of organized religion in the face of an indifferent world; and the way in which the past can enmesh us.

The story concerns Peplow, a mild-mannered bank clerk and RAF veteran, who travels with a hidden service revolver to Great Minden, a large village in Northamptonshire, on its annual feast day to find and kill the fairground ruffian he believes mowed down his 10-year-old son. There he discovers two wartime RAF mates: one is dying and the other is badly mutilated as a result of being shot down. It turns out to be a memorable hot day in summer for a number of people, mostly in ways they were not expecting.

It’s not, in essence, a credible tale, nor is it meant to be one, I suspect, although much has the stamp of autobiographical truth: the experiences and authentic talk of the RAF veterans, for example, echoed Jim’s time as a photographer and intelligence officer. There is also plenty of suggested sex of a transactional, farcical sort, the result, I imagine, of the lurid tales of village life he was told as a prim 18-year-old teacher by the school caretaker. It is rather ragged about the edges, as you might expect from a writer still learning his craft; he sets too many improbable sub-plots spin

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inNearly thirty years ago, I let down J. L. Carr, the novelist, and, as a result, regret grabs me by the throat every time I take down one of his books from the bookshelf. Reading A Day in Summer recently proved no exception.

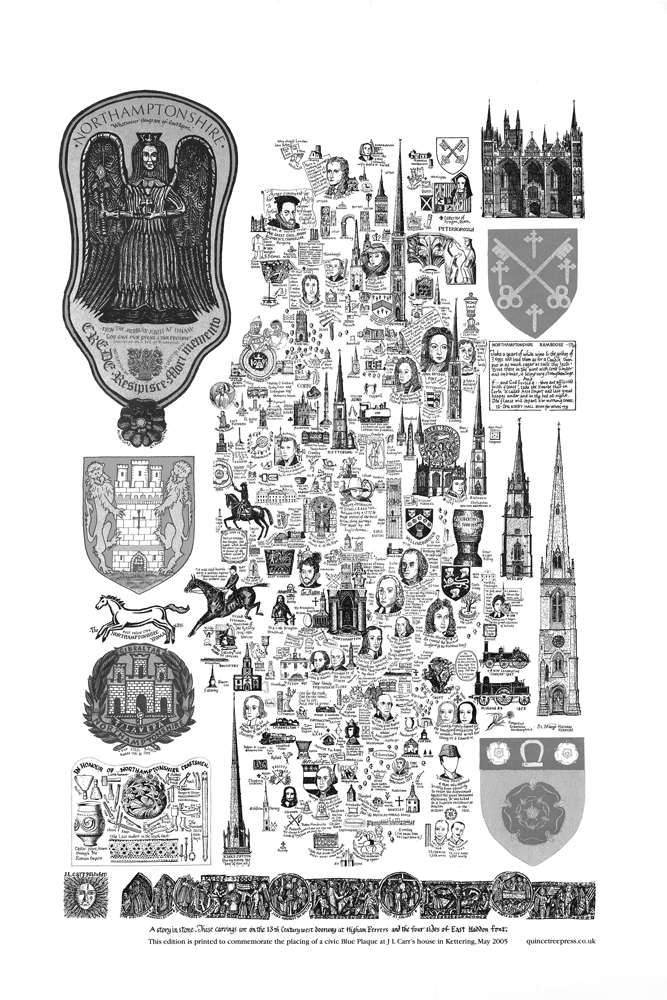

This was his first novel, published in 1963 by Barrie and Rockliff, the tenth publisher to whom he sent it. I have a great affection for it, perhaps because so many of his preoccupations are already revealed: an amused, sympathetic fascination with small, self-contained communities; the inability of men and women to understand each other; the unnerving backwash of memory experienced by those who have fought in a war; the decline of organized religion in the face of an indifferent world; and the way in which the past can enmesh us. The story concerns Peplow, a mild-mannered bank clerk and RAF veteran, who travels with a hidden service revolver to Great Minden, a large village in Northamptonshire, on its annual feast day to find and kill the fairground ruffian he believes mowed down his 10-year-old son. There he discovers two wartime RAF mates: one is dying and the other is badly mutilated as a result of being shot down. It turns out to be a memorable hot day in summer for a number of people, mostly in ways they were not expecting. It’s not, in essence, a credible tale, nor is it meant to be one, I suspect, although much has the stamp of autobiographical truth: the experiences and authentic talk of the RAF veterans, for example, echoed Jim’s time as a photographer and intelligence officer. There is also plenty of suggested sex of a transactional, farcical sort, the result, I imagine, of the lurid tales of village life he was told as a prim 18-year-old teacher by the school caretaker. It is rather ragged about the edges, as you might expect from a writer still learning his craft; he sets too many improbable sub-plots spinning, some of his characters are cartoonish and the ending feels both too melodramatic and too neat. Nevertheless, it is a beautifully written, funny and bleak novel, original and powerful enough to have attracted Alan Plater to write a masterly screenplay for a Yorkshire TV two-hour drama, transmitted in 1989, starring Peter Egan, Jill Bennett, Jack Shepherd, John Sessions and Ian Carmichael. I wish ITV would broadcast it again. Carr’s novels are very difficult to categorize, especially in subject matter and style: a flying-boat station in West Africa during the war; two damaged Great War veterans working on a church; a village football side winning the FA Cup; the adventures of an exchange teacher in a school in South Dakota; a year in the life of a primary school, told mainly by way of a school log; a bookish young woman in a Midlands boarding-house; two ex-teachers founding a publishing company. He had the capacity to transmute his experiences into tragicomic gold. Always, however, there is an underlying serious moral purpose which is scarcely a surprise, since Joseph Lloyd Carr was the son of a North Riding rural stationmaster and Wesleyan Methodist lay preacher, so his formative years were dominated by chapel going. What a precious heritage that turned out to be: close acquaintance with the Old Testament, in particular, provided him with such a rich legacy of stories, mostly of human frailty, that it is little wonder nothing ever seemed to surprise him. He had a sound opinion of his own worth; although not fazed by meeting dukes, he reserved most admiration and sympathy for the provincial and what was once called ‘the respectable lower middle-class’, whence he had sprung. After primary education in village schools, he went to Castleford Secondary School. He teasingly maintained in later life that his head-master there, T. R. Dawes, was a more remarkable man than the school’s most famous alumnus, Henry Moore. Dawes must have had a lasting influence on him, for Jim never lost the urge and capacity to learn and remember, reading widely and teaching himself to draw. He was a teacher, both in England and, for two short periods, in South Dakota, and then, from 1952, an inspirational, idiosyncratic headmaster of a primary school in Kettering. But he retired at the age of 55 to write more novels and to publish, from his back bedroom, illustrated ‘pocket books’ (mostly on poets) and large county maps, as well as his last two novels. The maps are miracles of stray facts, historical events and personalities, minute but oh-so-careful depictions of church spires and fonts, monuments, horses and country houses signifying villages and towns, and apposite quotations and sayings. The Northamptonshire map proclaims, ‘A county which, in a thousand places, mingled with and turned the flow of our nation’s history’. I got to know Jim (as he was known throughout his adult life) in 1980, soon after I married and went to live half an hour north of Kettering. We met at the home of an elderly mutual friend to whom he was showing slides of ‘The Treasures of Northamptonshire’. He impressed me with his phenomenal powers of observation, his sure taste and historical sense, and his fascination with country churches, one of which he had saved from dereliction despite all bureaucratic obstacles. I was struck too by his evident deep love for his adopted, rather disregarded county, a love I came to share. I also responded favourably to his pervading pessimism about the modern world, subverted by great good humour and wit. He was a Saxon, really; the human embodiment of Kipling’s ox in the furrow, but with an amused rather than sullen eye. Thanks mainly to him, since I was both shy and intimidated by his reputation, we became friends. In 1984, I started to write a column for the Spectator, and he would write encouragingly – in a black calligraphic script with masses of weird abbreviations – if a sentence or idea caught his eye. One July we met at the Spectator’s summer party in the Doughty Street garden, but, since neither of us knew any of the famous people there and it was plain that no one was going to introduce us, we talked comfortably to each other, then gave it up as a bad job and took the train back to Kettering. I have a photograph of him taken at my fortieth birthday party: a short man, dapper in linen jacket, striped shirt and old-fashioned cravat, clean-shaven with slicked-down hair, smiling like a benign but watchful churchwarden. He had an extraordinary range of acquaintance. I had married into the Kettering shoe- making aristocracy and those in that circle with aspirations to culture knew all about him. He did not hide his light under a bushel, if only because he had no marketing budget for his publications, so he welcomed a succession of journalists who wanted to write profiles of him. Byron Rogers, who later wrote an illuminating and readable biography, The Last Englishman, and the novelist and critic D. J. Taylor both became friends that way. He seemed to like other writers, which is by no means a given. With Dr Johnson, one of his heroes, he believed in keeping his friendships in constant repair. From time to time, I would get a witty letter, telling me of his travails at a literary prize-giving or asking me to check out some piece of church furniture in the north of the county, in his capacity as (a reluctant) secretary of the Northamptonshire Historic Churches Trust. When he visited us, he would empty his pockets of his little books. My husband and I take them with us on train journeys, as Jim intended. In our copy of The Battle of Pollocks Crossing (like A Month in the Country, it was shortlisted for the Booker Prize) he wrote, after a lunch at our house, an inscription that spanned the entire page, mostly about how much he had enjoyed talking about the Kettering ‘of the old days’ when it still had civic pride and a heart. How did I let him down? I was guilty of what Jim, who in later life became a faithful Anglican and lover of the Book of Common Prayer, might have called a sin of omission. I had left undone that thing which I ought to have done. He rang me in February 1994 and, without explanation, asked me to go to see him. It was a fraught moment for me; I had recently become a columnist on a Sunday newspaper and our house was being comprehensively renovated around us. Before I managed to get there, the call came to say that he had died. I see clearly now that, in his elliptical way, he was inviting me to visit so that he could say goodbye. It still pains me to think that I treated such an extraordinary man in such a very ordinary way.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 80 © Ursula Buchan 2023

About the contributor

Although Jim Carr warned that navigation by his county maps would be disastrous, Ursula Buchan still turns to them when planning any architectural tour.