It wasn’t at first sight the sort of book I would choose, but there was nothing else remotely interesting on the single shelf in the charity shop. The dust-jacket showed a number of vapidly drawn images of Parisian life in pale reds and yellows. The title, A Girl in Paris, was not encouraging. But on the back was glowing praise by Patrick Leigh Fermor for a previous work by the author, Shusha Guppy. I opened it and was hooked.

I should explain. I’ve always loved jazz and one of the earliest and greatest of all New Orleans musicians was the clarinettist and soprano saxophone player Sidney Bechet. Born in 1897, Bechet was a wandering spirit, performing before the royal family at Buckingham Palace in 1919, touring the newly born Soviet Union, and appearing in a silent film playing in a nightclub in pre-Nazi Berlin. In 1949 he settled in Paris and there he became an enormously popular entertainer, as well as maintaining a lifelong reputation as a relentless womanizer.

Here he is, in the mid-1950s, accosting the young and beautiful Shusha Guppy on a street in Paris:

‘Mademoiselle! . . . mademoiselle, excuse me . . .’ the chance of meeting anyone I knew in the middle of the day on the Right Bank was remote, but I turned my head, and saw an old black man approaching me, smiling.

His face was familiar . . . His picture was everywhere, playing his clarinet. Or smiling at the camera, his hooded eyes, squashed nose and round cheeks giving him the expression of a mischievous child . . .

He led me to the first café-terrace on the Champs-Elysées, and I told him that I heard his records every day, and that all the students loved his music. But he had more in mind than a

fan’s admiration . . .

Shusha Guppy had arrived in Paris from Tehran in 1950 aged just 16. The daughter of an intell

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIt wasn’t at first sight the sort of book I would choose, but there was nothing else remotely interesting on the single shelf in the charity shop. The dust-jacket showed a number of vapidly drawn images of Parisian life in pale reds and yellows. The title, A Girl in Paris, was not encouraging. But on the back was glowing praise by Patrick Leigh Fermor for a previous work by the author, Shusha Guppy. I opened it and was hooked.

I should explain. I’ve always loved jazz and one of the earliest and greatest of all New Orleans musicians was the clarinettist and soprano saxophone player Sidney Bechet. Born in 1897, Bechet was a wandering spirit, performing before the royal family at Buckingham Palace in 1919, touring the newly born Soviet Union, and appearing in a silent film playing in a nightclub in pre-Nazi Berlin. In 1949 he settled in Paris and there he became an enormously popular entertainer, as well as maintaining a lifelong reputation as a relentless womanizer. Here he is, in the mid-1950s, accosting the young and beautiful Shusha Guppy on a street in Paris:‘Mademoiselle! . . . mademoiselle, excuse me . . .’ the chance of meeting anyone I knew in the middle of the day on the Right Bank was remote, but I turned my head, and saw an old black man approaching me, smiling.

His face was familiar . . . His picture was everywhere, playing his clarinet. Or smiling at the camera, his hooded eyes, squashed nose and round cheeks giving him the expression of a mischievous child . . .

He led me to the first café-terrace on the Champs-Elysées, and I told him that I heard his records every day, and that all the students loved his music. But he had more in mind than a fan’s admiration . . .

Shusha Guppy had arrived in Paris from Tehran in 1950 aged just 16. The daughter of an intellectually distinguished, upper-class Persian family, her childhood and adolescence (beautifully described in her first book, The Blindfold Horse) had been sheltered and chaperoned. She had come to Paris to learn French before taking up a scholarship to study French Literature and Philosophy at the Sorbonne.

At first she was taken under the wing of a Persian (Shusha’s preferred adjective) diplomat, Mr Raheem. Raheem’s physically unprepossessing daughter Myriam told her of her ‘scores of suitors, each one of whom sounded a cross between Einstein and Clark Gable’ and introduced her to wine. Two glasses were quite enough for Shusha, inducing instant drunkenness and a lifelong aversion to alcohol.

She was relieved when she was able to take a room at the Benedictine Foyer for Young Ladies. The room’s furnishings were spartan: ‘a single iron bed, a table, two chairs . . . Its only luxury was a large wash basin.’ Which was just as well, since the hostel did not have a single bathroom.

It was only a few years after the end of the war, and Parisians complained that life was harder than during the Occupation. Certainly the Benedictine Foyer sounds fairly grim, the first autumn and winter being marked by ‘cold, hunger and loneliness’. No visitors were allowed in the rooms, the only exception being a retired one-legged army Major, who had an ‘understanding’ with Madame Giroux, the Directrice. A midnight curfew, after which the doors of the hostel were resolutely bolted, was Madame Giroux’s attempt to stem what she saw as the tide of post-war sexual freedom. But, as Shusha writes, the curfew that was ‘designed to protect the girls’ virtue produced the opposite effect . . . Many a Foyer student lost her virginity by being a few seconds late. Her boyfriend offered her hospitality for the night at his place, which was often no more than a tiny room with a single bed, and the inevitable happened.’

Shusha, cool, beautiful, extremely clever, seems to have been uninvolved in any love affair in her first year in Paris. Her main interest was in politics, and a new friend, Jeanette, introduced her to a Communist cell at the Sorbonne. Although her views in later life were far removed from the doctrinaire Left, like many others from rich and privileged backgrounds she felt both outrage and guilt at the poverty and inequality that existed in Persia. Not that the arid and narrow Stalinism of the French Communist party restricted her thought. As a student of Philosophy she reminds us of the richness of the early Arab philosophers and poets.

She also loved singing and went for lessons to Carlotta Bussoni, who, it was said, had been a celebrated soprano of the 1920s. Madame Bussoni wore ‘flamboyant mauves, violets and other bright colours, like some exotic bird . . . Her aquamarine eyes were surrounded with midnight-blue shadow . . . her straight nose seemed sculpted from thin ivory.’ The home life of this slightly fantastic woman was a mystery. It was difficult to tell how old she was. She lived with her son, a painter; ‘she mentioned him often as being talented, sensitive, beautiful’. Shusha got an early education in the discrepancy between artistic dream and cold reality when she arrived at a lesson and was told that Madame Bussoni was indisposed. Shusha discovered her address and went to visit, taking flowers. Her picture of the scene she encountered is unforgettable:

A woman in a flowery dressing gown was kneeling by the bed and sobbing: ‘Stop it! . . . Assez! Assez! ’ Her robe had slipped and bared a shoulder, and you could see her skeletal body . . . Her thin hair was stuck to her scalp, with a few yellow curls falling forward onto her forehead which she kept hitting with her knotted hands. The object of her supplication was a young man standing by a chest of drawers near the window: small, thin, with curly black hair and eyes that glinted in the penumbra like two embers . . .

This was Madame Bussoni’s ‘talented and refined’ son Jeanot, who periodically taunted his mother with her past history, one of love affairs, abortions and appearances in a string of dingy theatres in small provincial towns.

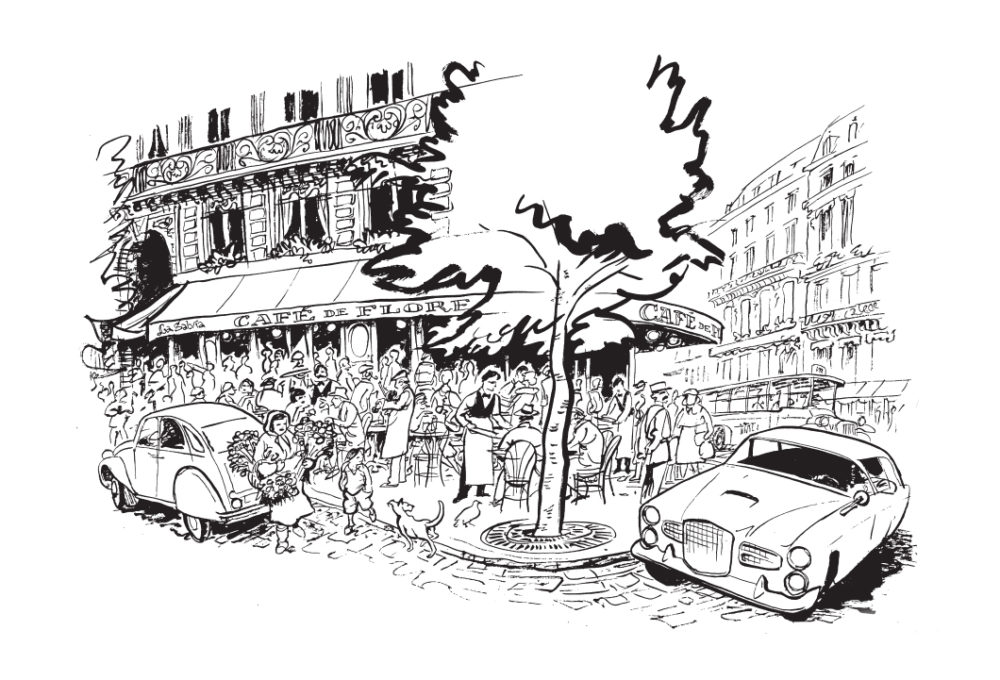

Shusha found other discordancies between truth and reality when she became acquainted with those stellar couples Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, and Louis Aragon and Elsa Triolet. Each couple, she writes, ‘was surrounded by a large and powerful court of princes, fools, and other hangers-on . . . and woe betide him or her who disagreed’. Even the cafés in which the Parisian intellectuals met were ideologically separated: the Surrealists at the Café Flore, the Communists next door at the Deux Magots. But one of those at the Café Flore was the poet and singer Jacques Prévert. Prévert, chainsmoking, a heavy drinker, almost 60, did not proposition or patronize Shusha. On hearing from her that the finest and most beautiful Persian carpets were made by little girls, put to work as young as 5, he won her heart by saying, ‘I don’t care about art, I want children to be happy.’

Prévert helped her to make her first recordings of Persian folk songs and when she had finished her studies she remained in Paris, scratching a living as a singer, model and part-time actress. An audition for a part in Lorca’s play The House of Bernada Alba attracted all the out-of-work actresses in Paris – a considerable number – and became, as Shusha describes it, ‘a cross between a brothel and an abattoir’. She got the part.

St-Germain-des-Prés was then in its last great days as a place where writers and artists still lived. Shusha became a feminist but learned to loathe Simone de Beauvoir, and she sided with Camus in his feud against the dreadful Sartre. At the end of the decade she returned home to Persia, and that is where her book ends too.

A Girl in Paris gives a wonderfully clear-eyed portrait of a city that, like all cities of our youth, has disappeared into time and memory. Read together with her account of her childhood in what was then called Persia, it offers the fascinating early history of a remarkable woman. In later years, Shusha Guppy married an Englishman and settled in London. She became a friend to a huge number of writers and artists and the great and good, and not so good, of high society. She died in 2008, a much-loved woman. But a friend, Ben Downing, recalled that for all her warmth and loyalty to her friends she could be engagingly egocentric; when he told her that he was about to read The Blindfold Horse, she said, in what he called her ‘Zsa Zsa Gaborian’ husky voice: ‘My dear, how I envy you the pleasure.’

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 26 © William Palmer 2010

About the contributor

William Palmer has published six novels and two collections of poems. Three of his novels, The Good Republic, Four Last Things and The Pardon of Saint Anne, were reissued in 2009 by Faber Finds. He has just completed Under the Influence, a study of alcohol in the lives and work of writers.