Try it yourself. Assemble a handful of chaps of pensionable age – because these will be men whose voices were wavering between treble and tenor in the 1950s – and ask them if they remember the name Hank Janson. I guarantee you an interesting reaction – first the joy of slowly dawning recognition, then a shifty flush of guilt as they realize why they remember it so well. During the Fifties Hank Janson was by far the most famous writer of sexy books in Britain. These days, young men have sex education. Then, ten years after the war, we had Hank.

If I may remind you of that distant time. There were no bare breasts in the tabloids, no contraceptive pill for either the day before or the morning after, no half-naked ladettes writhing on the pavements of an evening, no sex lessons featuring courgettes, almost no single mums. Our television chef, a plump little chap with a beard called Philip Harben, never used the f-word but quite often the gwords: gosh and golly. A cry of ‘Get them out for the lads’ would have meant nothing to anyone. Hard to imagine, but it’s true. With so little information, it’s a miracle the human race didn’t die out. As I say, all we had was Hank, which is probably why, six decades later, his name is still remembered with mingled pleasure and shame.

I thought I was the only one who remembered him until I came across his name in Simon Gray’s diaries. ‘The titles alone drove my blood wild – Torment for Trixy – Hotsy, You’ll Be Chilled,’ he wrote. Gray had a secret library of Jansons: he ripped off the lurid covers before squirrelling the books away in his bedroom, often under loose floorboards. When he discovered at the age of 65 that there was a whole website devoted to Hank and his works, he was quite beside himself: ‘I really went through the most astonishing tumble of emotions, the confusion of desire and thrilled shame.’

Now I wouldn’t for a moment suggest that reading Hank helped

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inTry it yourself. Assemble a handful of chaps of pensionable age – because these will be men whose voices were wavering between treble and tenor in the 1950s – and ask them if they remember the name Hank Janson. I guarantee you an interesting reaction – first the joy of slowly dawning recognition, then a shifty flush of guilt as they realize why they remember it so well. During the Fifties Hank Janson was by far the most famous writer of sexy books in Britain. These days, young men have sex education. Then, ten years after the war, we had Hank.

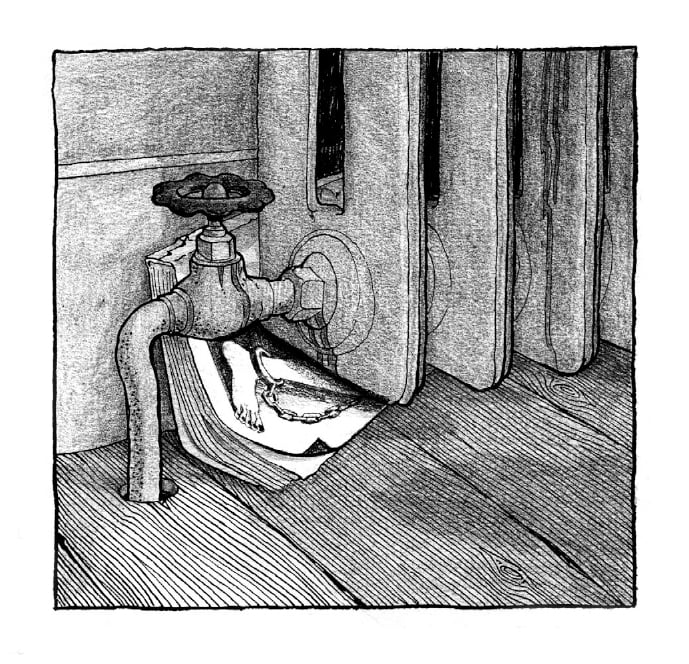

If I may remind you of that distant time. There were no bare breasts in the tabloids, no contraceptive pill for either the day before or the morning after, no half-naked ladettes writhing on the pavements of an evening, no sex lessons featuring courgettes, almost no single mums. Our television chef, a plump little chap with a beard called Philip Harben, never used the f-word but quite often the gwords: gosh and golly. A cry of ‘Get them out for the lads’ would have meant nothing to anyone. Hard to imagine, but it’s true. With so little information, it’s a miracle the human race didn’t die out. As I say, all we had was Hank, which is probably why, six decades later, his name is still remembered with mingled pleasure and shame. I thought I was the only one who remembered him until I came across his name in Simon Gray’s diaries. ‘The titles alone drove my blood wild – Torment for Trixy – Hotsy, You’ll Be Chilled,’ he wrote. Gray had a secret library of Jansons: he ripped off the lurid covers before squirrelling the books away in his bedroom, often under loose floorboards. When he discovered at the age of 65 that there was a whole website devoted to Hank and his works, he was quite beside himself: ‘I really went through the most astonishing tumble of emotions, the confusion of desire and thrilled shame.’ Now I wouldn’t for a moment suggest that reading Hank helped the late Simon Gray become one of our most distinguished playwrights, but if his memory was imperishable for the two of us, how many others still dreamed of Torment for Trixy? When confronted with a dilemma of this nature, I rely on the Petersfield Golf Club test. If you do not already know this, the Petersfield seniors are respectable retirees, men whose BMWs bear a shine to match that of their polished brogues: they pay their taxes, prune their privets and seldom do anything to frighten the horses. I asked a dozen of them if they remembered the name. They all did, with one exception. ‘Aha, you must be referring to the author of those racy crime thrillers,’ said Peter. ‘They were well-thumbed and passed from one adolescent to another.’ Clive’s response was even more accurate: ‘Pulp-fiction writer who specialized in potboiler thrillers featuring lurid sexual exploits (very anodyne by today’s standards).’ John pointed out that they were not books you wished your mum to find you reading and Des recalled that they were sold in brown paper wrappers – ‘hence the brown paper carpet in my bedroom’. If Simon Gray and the grandees of the Petersfield Golf Club can cherish these memories, I feel a little less self-conscious about my own. At Ermysted’s Grammar School in the Yorkshire Dales, on the rare occasions when we got our grubby paws on a Hank Janson, we fell upon it like wolves. For younger readers, I must point out that our entire sex education consisted of the sports master, Mr Swainson, giving a mumbled and red-faced account of the reproductive system of the frog. (This could account for the fact that many of my schoolmates were strangely drawn to women with long legs, bulging eyes and cold skin. Luckily, they were not in short supply in Yorkshire.) However, that was all the information we had to go on. A few hundred yards up the road, the pupils at Skipton Girls’ High School could have helped out but seemed unwilling to do so. If you were to walk up the Ermysted school drive now, turn left under the arch into the third-form block, immediately right into the cloakroom, then fish behind the huge old iron radiator in the corner, you might well find Skirts Bring Me Sorrow, which I left there in 1954. I seem to remember someone’s older brother had bought it from a stall in Bradford market. We kept it rolled up behind the radiator and, between double physics and Latin, four or five of us – with one on sentry duty – would retrieve it and read out the rude bits. I have it here before me. Not the original, of course, but a reissue by the small publisher Telos, who have reprinted a range of Hank’s books. The cover prices it at 1s. 6d, describes Hank as ‘Britain’s bestselling American author’, and bears an illustration of a long-legged redhead wearing a silk rag held in place only by her remarkable thoracic development. It was illustrations such as this, together with the tough-guy titles, that made the books so irresistible. Nothing in our previous reading – ‘Wilson the Wonderman’ in the Wizard comic and Red Circle school adventures in Hotspur – had prepared us for When Dames Get Tough, Sweetheart, Here’s Your Grave and – my personal favourite – Slay-Ride for Cutie. Each had a cover showing a half-naked woman, sometimes chained or roped, and usually staring in some fear at something unspeakable about to happen just outside the frame. As we huddled over Skirts Bring Me Sorrow in the cloakroom, we rather thought she might be looking out for our headmaster, M. L. Forster, who was a deft hand with the bamboo cane himself. So who was Hank? His cover biography makes Ernest Hemingway sound like a bookworm. Born in England, stowed away on a fishing trawler, dived for pearls in the Pacific, spent two years whaling in the Arctic, worked all over America as a truck-driver, news reporter and private detective. Served in Burma during the war. Returned to England where he spends his time gardening and writing in Surrey. It sounds almost as if someone had made it up. Someone had. Hank, as it happens. This was one of his better pieces of fiction, to fit the image his readers wanted. The truth is less picaresque. Stephen Daniel Frances – his real name – was born and brought up in grim poverty in South London. Fiercely left-wing, during the First World War he was a conscientious objector. Later, after producing a few articles, he founded a small publishing company and began writing his tough, sexy thrillers. He took the name Hank because it rhymed with Yank, although Stephen Frances himself never set foot in America. As far as readers were concerned, Hank Janson was the author and, as crime reporter for the Chicago Chronicle, the hero. Frances almost seemed to believe his own publicity. In his rare interviews, he appeared as Janson with a hat and a mask. The books just rolled out: Lady, Mind that Corpse – Smart Girls Don’t Talk – Baby Don’t Dare Squeal – Don’t Mourn Me Toots. And they sold in their millions. Every six weeks a new story about fillies and frails and broads ran off the press, 100,000 copies of each for his readers, waiting clammy-handed. Even that wasn’t enough. When Stephen Frances tired of being Hank Janson he would become Ace Capelli, Johnny Grec or Duke Linton. At one time he was producing a book a week, nearly 300 altogether, with sales of over 13 million in the Forties and Fifties. While one book was being typed for the printer, he was already well into the next one; sometimes five titles were being printed simultaneously. ‘I felt more like a factory than an author,’ he said. A profitable factory though. He drove a Daimler and bought a home in Spain, where he died in 1989. He liked to claim that he had vicars and doctors among his readers, and no doubt he did. But most of his books, I suspect, would have been found in Army camps and factories, not to mention behind my school radiator and beneath Simon Gray’s floorboards. Hank started publishing in 1948 but didn’t hit trouble until the end of paper rationing in the 1950s produced a flood of magazines and books, and Britain was able to indulge in one of its periodic attacks of Puritanism. The police began raiding bookshops and newsagents, seizing and destroying thousands of ‘obscene’ books and prosecuting booksellers. His distributor went to jail. Hank had a near miss. Asked if he was the writer of these obscene books, he denied it. It was the truth. As he pointed out later, he didn’t write them, he dictated them. His publishers went into liquidation, booksellers and newsagents were reluctant to stock him, and no one wanted to defend poor old Hank. But then the tide turned. When the same obscenity laws were used against serious books, there were letters to The Times and voices raised in Parliament. Steve Holland, author of The Trials of Hank Janson (also republished by Telos), says: ‘Few writers can be said to have had such an impact on literature. Without Janson, we might still be reading expurgated versions of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and Fanny Hill might be consigned to history.’ I can’t say that influencing the course of English literature was at the forefront of my mind as we crowded over our copy in the cloakroom, and I doubt if Simon Gray’s thoughts went in that direction either. Steve Holland says the books were real page-turners and were written with a breathless energy that makes them very readable. So sixty years on, I picked up Skirts Bring Me Sorrow to see if I could find what it was that held me, most of Ermysted’s third-form, Simon Gray and half the members of the Petersfield Golf Club in thrall all those years ago. And there it all was: ‘magic shudders of pleasure . . . a dame who’d been starved of love . . . the fragrance of her bare shoulder . . . deliciously quivering beneath my hot hands . . . her mouth was moist and hungry . . .’ – the book was deliciously quivering in my hot hands. Now I remembered what it was we found in Hank Janson. There was no information about sex, none whatsoever. What he showed us was the wicked excitement and danger of sex. That was something you couldn’t get from tadpoles and for that alone we owe him something. And did it deprave and corrupt us? Oh, I expect so. You only have to look at the Petersfield Golf Club seniors to see that.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 33 © Colin Dunne 2012

About the contributor

Colin Dunne has published eight novels and written articles and columns for everyone from the Mirror to The Times. His career as a writer, a story marked for the most part by cruel humiliation and bitter disappointment, is recorded in his latest book, Man Bites Talking Dog.