For the past couple of years I’ve been researching a book about the Greene family. The Greene King brewery, on which its fortunes are based, dates back to the Napoleonic period, but since I’m allergic to dynastic histories I’ve decided to concentrate on one generation: Graham Greene’s siblings and first cousins, all of whom grew up in the same small town in the early years of the last century.

Graham Greene himself has been written about at inordinate length already, not least in Norman Sherry’s three-volume life, so I doubt if I’ll have anything new to say about him: but other members of his generation more than compensate. They include the black sheep of the family, who spied for the Japanese in the 1930s, wrote a fanciful account of his adventures in the Spanish Civil War, and led a nationwide campaign against his youngest brother’s decision to move the nine o’clock news on the BBC Home Service to ten and phase out the bongs of Big Ben; a brilliant mountaineer who joined Eric Shipton and Frank Smythe in their 1933 attempt on Everest before becoming a pioneer endocrinologist, famed for diagnosing Guy the Gorilla’s thyroid problems; and an idealistic member of the Labour Party who fell into bad company shortly before the war, and was banged up in Brixton in 1940 under Regulation 18b at the same time as Oswald Mosley. Add to these the BBC’s first North America correspondent, who became a disciple of Krishnamurti and an enthusiastic apologist for Mao and Communist China; the even more distinguished employee of the BBC who infuriated his older brother by tinkering with the nine o’clock news; and a pampered daughter who – to the surprise of all who knew her – wrote one of the most entertaining travel books of its time.

Looking back to the 1930s, Graham Greene once wrote that ‘It was a period

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inFor the past couple of years I’ve been researching a book about the Greene family. The Greene King brewery, on which its fortunes are based, dates back to the Napoleonic period, but since I’m allergic to dynastic histories I’ve decided to concentrate on one generation: Graham Greene’s siblings and first cousins, all of whom grew up in the same small town in the early years of the last century.

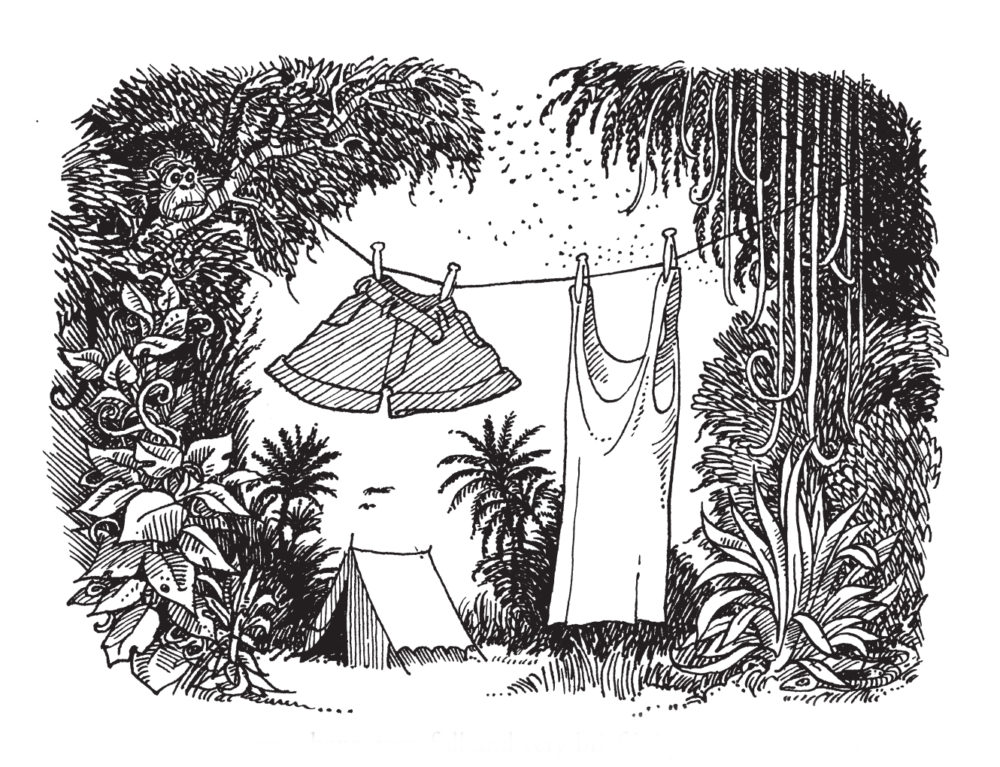

Graham Greene himself has been written about at inordinate length already, not least in Norman Sherry’s three-volume life, so I doubt if I’ll have anything new to say about him: but other members of his generation more than compensate. They include the black sheep of the family, who spied for the Japanese in the 1930s, wrote a fanciful account of his adventures in the Spanish Civil War, and led a nationwide campaign against his youngest brother’s decision to move the nine o’clock news on the BBC Home Service to ten and phase out the bongs of Big Ben; a brilliant mountaineer who joined Eric Shipton and Frank Smythe in their 1933 attempt on Everest before becoming a pioneer endocrinologist, famed for diagnosing Guy the Gorilla’s thyroid problems; and an idealistic member of the Labour Party who fell into bad company shortly before the war, and was banged up in Brixton in 1940 under Regulation 18b at the same time as Oswald Mosley. Add to these the BBC’s first North America correspondent, who became a disciple of Krishnamurti and an enthusiastic apologist for Mao and Communist China; the even more distinguished employee of the BBC who infuriated his older brother by tinkering with the nine o’clock news; and a pampered daughter who – to the surprise of all who knew her – wrote one of the most entertaining travel books of its time. Looking back to the 1930s, Graham Greene once wrote that ‘It was a period when “young authors” were inclined to make uncomfortable journeys in search of bizarre material – Peter Fleming to Brazil and Manchuria, Evelyn Waugh to British Guiana and Ethiopia. Europe seemed to have the whole future; Europe could wait.’ In later life Greene was the most footloose of authors, criss-crossing the globe to keep boredom at bay, find material for his fiction and gratify an endearingly adolescent passion for leaping on aeroplanes, but he made his mark as a travel writer in the pre-war years. Journey without Maps and The Lawless Roads are among the great travel books of the twentieth century, and describe journeys of extreme discomfort, in Liberia and Mexico respectively: but whereas Greene set out alone to investigate the persecution of the Church in Mexico’s deep south, he took a travelling companion on his journey to Liberia. This was reasonable enough, since the country was notoriously primitive, largely unexplored and blighted by tribal warfare: but far from enlisting some gnarled, leather-skinned veteran of the bush, adept at spearing wild game and lighting fires, and fluent in innumerable native tongues, he found himself saddled with a willowy London socialite accustomed to a life of luxury and endless party-going. Appropriately enough, it all began at a party. Graham’s youngest brother, Hugh – then newly appointed to the Daily Telegraph’s Berlin office, and years later the BBC’s most controversial Director-General – married Helga Guinness, of the banking and brewing dynasty, in the autumn of 1934. Among the guests crowding Chelsea Old Church were Graham, already making his mark as a novelist and all-round man of letters, and their 27-year-old cousin Barbara. Graham had been commissioned by his publishers to visit Liberia; Barbara was at a loose end; after several glasses of champagne at the reception, he asked if she would like to come with him, and she rashly agreed. Both soon had second thoughts. Graham deluged Barbara with blood-curdling accounts of the squalor and diseases prevalent in the interior of Liberia and the massacre of its people by government forces, and pointed out that on some maps large areas of the country were simply marked ‘Cannibals’ and ‘Wild Animals’. Barbara was duly unnerved, and went to her father for advice. ‘“Papa,” I said timidly, “I’ve done a very silly thing. I’ve told Graham I’d go to Liberia with him.” My father, after only a moment’s pause, answered quietly but firmly: “At last one of my daughters is showing a little initiative.”’ There was nothing for it but to press ahead. ‘I wept a little, and boasted a lot, and tried very hard to look like an explorer as I left London in a thick mackintosh and a “sensible” hat,’ Barbara recalled. Whereas Cousin Graham took Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy as his reading matter, Barbara packed stories by Saki and Somerset Maugham, and in Freetown she ordered a pair of shorts from a local tailor. They were ‘of strange shape, very full and very brief, that somehow managed to look like a ballet skirt. I am tall and hefty and later, as we got tired towards the end of our trip, these shorts were to get so much on my cousin’s nerves that he was ready to scream every time he saw them.’ Although the two cousins had spent their early lives in close proximity, ‘we had never had a great deal to do with one another before Fate and champagne decided to link our lives in this way’. Graham’s father, Charles, had been the headmaster of Berkhamsted School, and he and his wife – also a Greene – had six children; his brother Edward, Barbara’s father, had made a fortune from the coffee trade, and after he came home from Brazil he bought a vast house at the other end of Berkhamsted, where he lived with his German wife and their six children. The ‘rich’ or ‘Hall’ Greenes lived in a world of servants and plenty, and were rather in awe of the ‘intellectual’ or ‘School House’ Greenes, who were high-minded, bookish and relatively hard-up. In later years Barbara and Graham became good friends, but one would hardly guess it from his account of the time they spent together plodding single-file through the jungle and camping out in squalid, bug-ridden villages replete with mud huts and tribal dancers. Poor Barbara barely gets a mention in Journey without Maps: she is never referred to by name, and as ‘my cousin’ makes only the most sporadic appearances. Long afterwards, Greene offered an explanation. Most of the journey was, as they both admitted, numbingly tedious, with ‘memories chiefly of rats, of frustration, and of a deeper boredom than I had ever experienced before’: there was nothing to describe in terms of buildings or scenery, and ‘if this was an adventure it was only a subjective adventure, three months of virtual silence, of “being out of touch”’. He made the narrator into an abstraction, in search of archetypes of innocent, uncorrupted man, and ‘to all intents I eliminated my companion’. Barbara, he conceded, ‘proved as good a companion as the circumstances allowed, and I shudder to think of the quarrels I would have had with a companion of the same sex’. ‘Only in one thing did she disappoint me – she wrote a book,’ Greene continued, before admitting that he had never noticed that Barbara, too, was making notes as they went. Published in 1938, Land Benighted is a neglected masterpiece – funny, observant, good-humoured, knowingly inaccurate only in its claim that she was a mere 23 at the time, and a marvellous counterpoint to Greene’s more serious and self-absorbed account, which had been published two years earlier and, much to his annoyance, had been withdrawn pending a possible libel suit by the time his cousin’s book came out. ‘Should the reader of this book lean towards the roaring lion type of adventure, let him cast this volume from him. The beasts of the forest kept away from us, the natives were friendly, our adventures were more amusing than frightening, and good luck dogged our footsteps for most of the time,’ she warns us; and, unlike her cousin, she devotes a good deal of space to her travelling companion. He was, she noted, ‘vague and impractical’, yet ‘I was continually astonished at the efficiency and the care which he devoted to every little detail.’ He addressed their bearers in ‘rather literary English’, but treated them as equals even if ‘his method of conversation was far from simple’. He had, she noted, ‘a permanently shaky hand, so I hoped that we would not meet any wild beasts on our trip’. Greene may have treated their ‘boys’ like a ‘benevolent father’, but he could be daunting at times. ‘His brain frightened me. It was sharp and clear and cruel,’ Barbara confessed.Apart from the three or four people he was really fond of, I felt that the rest of humanity was to him like a heap of insects that he liked to examine, as a scientist might examine his specimens, coldly and clearly. He had a remarkable sense of humour and held few things to be too sacred to be laughed at. I suppose at that time I had a very conventional little mind, for I remember he was always tearing down ideas I had always believed in, and I was left to build them up anew.Even so, she thought him the best kind of companion for a trip of this kind. As they marched in silence for hours on end, through head-high jungle with views to neither side, she became obsessed by the way his socks slowly slid down over his shoes, ‘in little round wrinkles, like a concertina’: ‘“I wish he would pull up his socks,” I said to myself, as we were striding along, for by this time I had got well into the way of talking to myself as if I were two people.’ Towards the end of the trip he was laid low with fever, by which time she had discovered that she liked Graham and respected him. Despite the filth, the exhaustion, the ants and the jiggers that dug into the soles of their feet, ‘the beauty of the villages, the courtesy of the natives, the music, the dancing, the warm moonlit nights were things that gladdened the heart anew every day’. When the jungle seemed ‘dead, untidy, endlessly big but without any vitality’ and the rats had chewed the bristles off her hairbrush, Barbara longed to be back in London, yet

it is strange, and perhaps rather horrible, how quickly we adapt ourselves to our surroundings. My life in England had been led in pleasant places . . . I had been used to well-cooked food and beautiful clothes, a lovely house filled with people who smoothed out for me as far as possible the rough patches . . . In Liberia I was surrounded by rats, disease, dirt, and foul smells, and yet in a very few days I had sunk to that level and did not mind at all.Like all the best travel writers, Barbara has an eye for the telling detail. The President of Liberia bustles in ‘looking as if he had just left the Fifty Shilling Tailors’. The food is unremittingly repellent, and while Graham dreams of steak and kidney pudding, she yearns for smoked salmon. They encounter Colonel Davis, the notorious Dictator of Grand Bassa, a Black American held responsible for the massacre and torture of Kru women and children, and he tells them of his passion for Ovaltine and the important role he plays in Liberia’s Boy Scout movement. Graham develops a nervous tic over his right eye, which exercises a hypnotic fascination. The war broke out a year after publication of Barbara’s book: she was in Berlin at the time, and spent the next six years in Germany. She married Count Strachwitz, a German diplomat who later served as Ambassador to the Vatican, and she herself eventually became a Catholic and a stickler for protocol. Land Benighted was reissued in 1981, with a less contentious title – Too Late to Turn Back – and an enthusiastic introduction by Paul Theroux. It’s time it saw the light of day once more.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 18 © Jeremy Lewis 2008

About the contributor

The third volume of Jeremy Lewis’s autobiography, Grub Street Irregular, was published in July 2008, and his book on the Greene family came out later that year.